Chapter 14 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

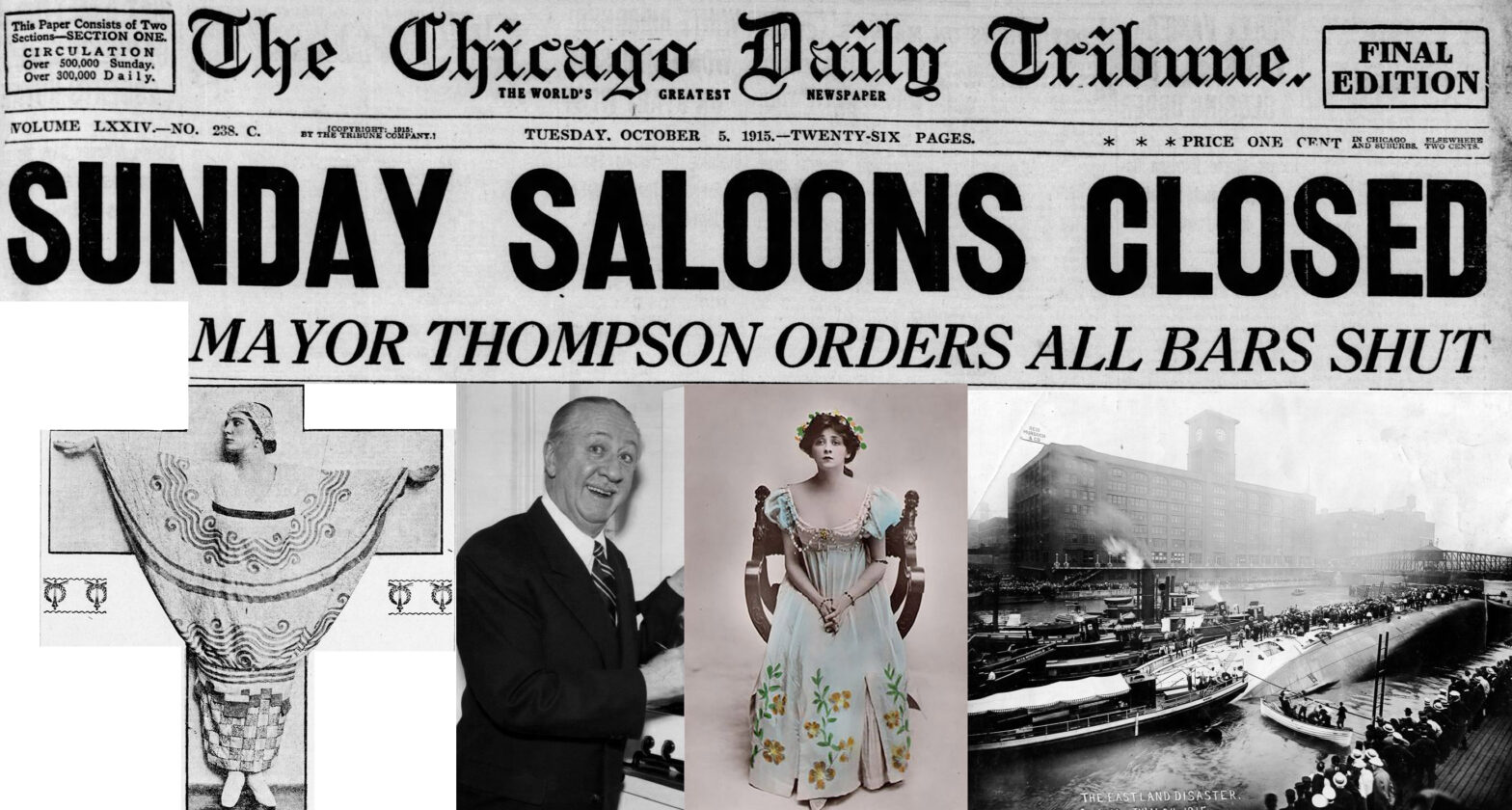

In 1915—the same year when jazz music was written about for the first time—the biggest event at Green Mill Gardens may have been a charity show on August 4. Entertainers raised money for the families of people who’d died when the Eastland excursion boat capsized in the Chicago River.

The charity event came in the midst of a year when Green Mill Gardens continued to establish itself as one of Chicago’s leading entertainment venues—and as the place occasionally popped up in newspaper stories about crime. At the same time, the campaign to restrict alcohol was intensifying, leading to a surprise decision that fall by Chicago mayor Bill Thompson.

The benefit performance took place 11 days after the Eastland disaster, when 844 people lost their lives the deadliest catastrophe in Chicago history.1

Eastland Disaster Historical Society

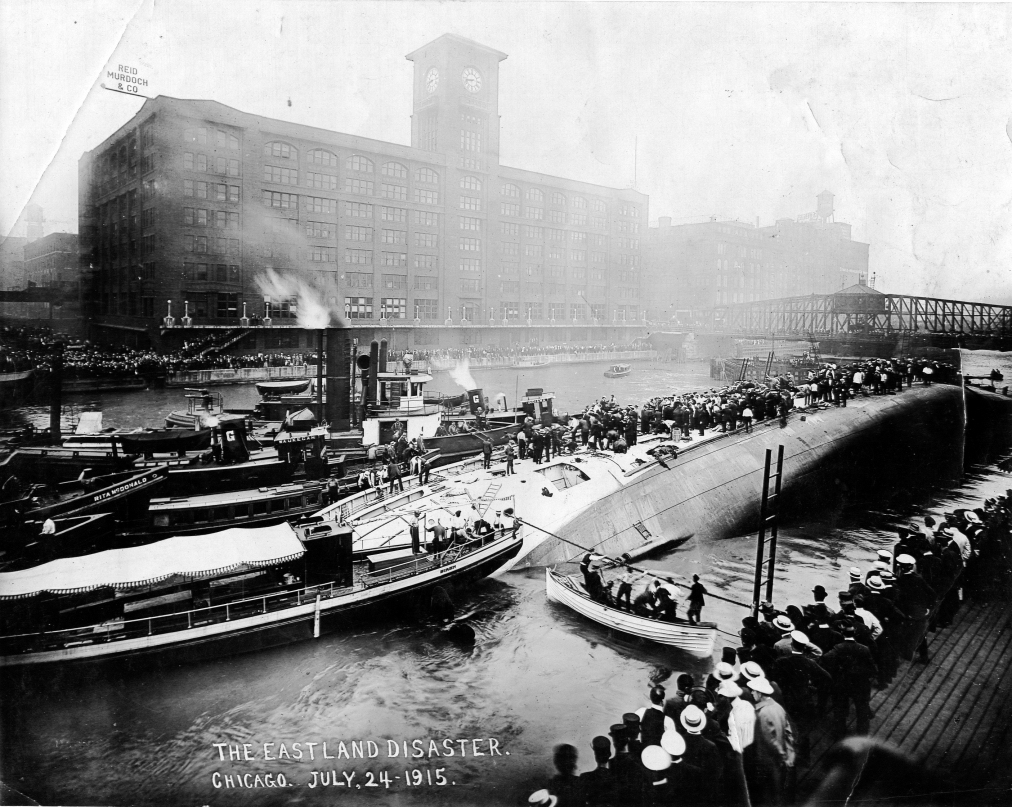

The Chicago Daily Tribune’s circulation manager, Max Annenberg, organized the event, working with a group called the Good Fellows of the North Side.2

Max and his brother, Moses, were immigrants from Germany who led violent mobs that enforced newspaper delivery during the early 20th century’s “Newspaper Wars” between the Tribune, William Randolph Hearst, and other publishers.3 During the course of these bloody confrontations, Max Annenberg had employed “bullies and ex-boxers” who “pummeled newspaper sellers with blackjacks and brass knuckles,” Wayne Klatt wrote in Chicago Journalism: A History.

The burly Annenberg “was courageous, a little uncouth, and aggressively friendly, thumping female stenographers on the rump as he strode toward his carpeted office,” Klatt wrote. “Wanting class, he wore turtleneck sweaters and kept his checkered cap at a tilt. He also learned to play golf just like the newspaper executive he practically was.”4

At this time in 1915, Max was living at 4741 North Malden Street, a few blocks from Green Mill Gardens.5 (His brother Moses’s son Walter later became a well-known philanthropist, starting the Annenberg Foundation.)

The Green Mill Gardens show assembled entertainers from downtown theaters and other venues. They promised to present “fresh stuff” and “new business” rather than simply repeating old routines. According to Annenberg, they were “burning the midnight oil to demonstrate originality” as they prepared for this all-star show.6

“The Green Mill gardens performance will be worth double the admission charged,” the Tribune wrote, as it urged Chicagoans to buy 50-cent tickets. “Hundreds of bereaved families will be without food or shelter unless many charitable persons respond to the urgent appeal,” the newspaper said.7 The event raised $1,032.52 (or more than $30,000 in today’s dollars).8

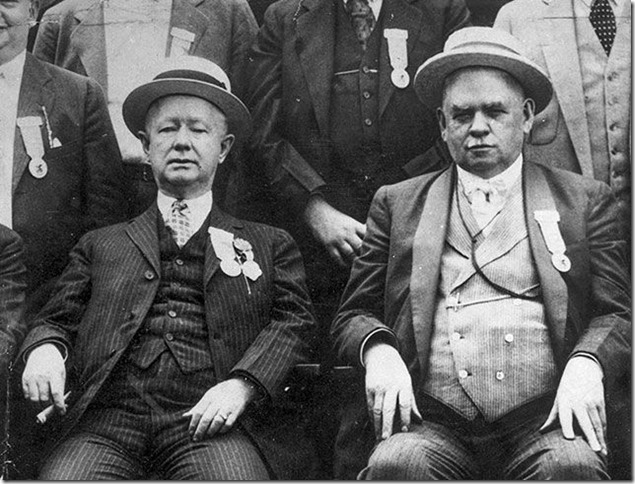

The performers included Green Mill Gardens regular Isabella Patricola, as well as the cast of Maid in America. (The performers in that show had recently championed the cause of Brown’s Band, the New Orleans group playing music that some folks described with a new word, jazz. See Chapter 12.) The benefit also featured:

“An exhibition of fancy dancing” by Miss Margaret Rafferty (a.k.a. Marguerite Kenvin Rafferty), who was shown striking a perky pose in a Tribune photo.9

Rita Gould, a singer born in Odessa known for her dramatic costumes and gestures,10 who said, “In many of my song numbers I illustrate my meaning with hand and arm movements and body swaying.”11

Valli Valli, a Berlin-born stage actress who also appeared that year in the movies The High Road and The Woman Pays.12

Joseph Santley, an actor-singer-dancer-writer-director-producer who’d created dances called the Santley Tango and the Hawaiian Butterfly, and would later co-direct the Marx Brothers’ first movie, The Cocoanuts.13

And actor-comedian-composer Roy Atwell, whose characters often stammered or fumbled their words. He would later provide the voice of Doc for Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.14

Other entertainers at Green Mill Gardens in 1915 included Ray Raymond,15 an actor and singer known for musical comedy. That same year, he appeared on screen in The Mystery of the Silent Death, a movie by the Essanay company, which had a studio just a few blocks from Green Mill Gardens.16

That September, Green Mill Gardens owner Tom Chamales hosted a dinner at the venue for some of the city’s most famous baseball stars—pitcher Mordecai “Three-Finger” Brown, shortstop Joe Tinker, and second baseman John Evers—along with Cubs treasurer Charles Williams. The Daily News called them “remnants of the old Cub machine,” referring to the Chicago Cubs team that had won the World Series in 1907 and 1908, when Tinker and Evers were two-thirds of the legendary triple-play combination “Tinker to Evers to Chance.” Brown and Tinker had moved over to the Federal League, where they played in 1915 for the Chicago Whales at Weeghman Park (which would soon become Wrigley Field when the Federal League folded).17

In December 1915, an advertisement announced that “Mr. and Mrs. Carl Heisen, Chicago’s Favorite Dancers, Including Their Famous Orchestra will appear every evening at Green Mill Winter Gardens.”18 Heisen, who was born in Chicago, would later use the stage name Carl Hyson. His wife and dancing partner—who would eclipse him in fame—was Dorothy Dickson, who came from Kansas City, Missouri. They lived in Chicago’s west suburbs, residing at times in Villa Park and Elmhurst,19 but two years after their stint at Green Mill Gardens, they performed in the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway.

They moved to England in 1921, where Dorothy Dickson became a star of the London stage, performing the original versions of two songs that became standards, “Look for the Silver Lining” and “These Foolish Things.” (Here’s a medley of her singing those hits along with several other songs.) Dickson—who lived until the age of 102, dying in 1995—was reportedly a longtime friend of Queen Mother Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, the mother of Queen Elizabeth II.20 Dorothy and Carl’s daughter, who was born in Chicago on December 24, 1914, one year before her parents started dancing at Green Mill Gardens,21 was a star of stage and screen as Dorothy Hyson, marrying Sir Anthony Quayle and thus becoming known as Lady Quayle. She reportedly inspired Rodgers and Hart’s song “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World.”22

Miscellaneous mayhem

Almost as soon as Green Mill Gardens was open, the place was mentioned in newspaper articles about crimes. Of course, the venue couldn’t be blamed for most of these incidents. As a popular gathering spot on Chicago’s North Side, it was simply the sort of place where people came together in large crowds at nighttime. And whenever that happens, there are bound to be moments of conflict or underhanded behavior. Nevertheless, these stories may have contributed to the sense that Green Mill Gardens was contributing to an increase in crime and mayhem.

In early August 1914, not even two months after Green Mill Gardens opened, the venue’s head waiter, Sam Borris, reportedly stabbed another man in a quarrel over work.23

On November 20, 1914, Nicholas T. Burns, a wealthy manufacturer of rope and marine supplies, was found dead in front of 4948 North Sheridan Road—three hours after he’d been seen with two men at Green Mill Gardens.24 He’d been poisoned with potassium cyanide.25 The crime was apparently never solved.

And in July 1915, the Day Book newspaper reported: “Police interrupted merry party of men and women in bachelor apartments, 4643 Malden av. Men said they had picked up girls in Green Mill Gardens.”26

The big Sunday shutdown

In the fall of 1915, the future of Green Mill Gardens and Chicago’s other amusement gardens was thrown in question with a bombshell news story. Five months after becoming mayor, William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson stunned Chicago on the night of October 4, 1915, when he signed an order declaring that the city would finally enforce an old state law against selling alcohol on Sundays at barrooms, cafes, restaurants, hotels, and clubs.

The mayor’s declaration came nearly eight years after a jury found Tom Chamales not guilty of breaking the same state law, leading many people to think that the law against Sunday saloons would never be enforced in Chicago. (See Chapter 5.) And Thompson’s announcement was doubly surprising because he was known as a politician who would allow a “wide open” city where these sorts of laws weren’t enforced.

Thompson was leaving town at midnight—boarding a train to the world’s fair in San Francisco—when he issued the decree. His statement was read aloud at a City Council meeting that was in session at midnight, with a large crowd filling the galleries. “It was received at first with a gasp of surprise,” the Tribune reported. “… There was a ripple of handclapping, chiefly from the women.”27

“Here’s the explanation: It’s the law,” Thompson told reporters aboard his train around 2 a.m. “… When the corporation counsel told me it was the law, why, then, I made the decision. When Big Bill Thompson puts his hand above his head and says he will enforce the law he means it.”

Another official on the train, deputy commissioner of public works Billy Burkhardt, said he’d received a phone call that night from Tom Chamales. “He said he had a bartender who hadn’t had a Sunday off in 12 years,” Burkhardt said. “Think of that! Chamales said most of his Sunday business was restaurant business, anyway. It would be a big boost for the sale of bottle beer, Chamales said, too.” Thompson laughed as he heard Burkhardt recounting this conversation with Chamales.28

Billy Sunday, the former Chicago White Stockings player who’d quit baseball to become America’s most famous evangelist preacher of the early 20th century, issued a statement from Omaha, Nebraska: “I am glad I have lived long enough to see a man elected mayor of Chicago that had the grit and the backbone to close the saloons on Sunday. … I can imagine the howl when the news reached hell, and I am sure the devil is in bed with pneumonia.”29

An anti-temperance organization called the United Societies for Local Self-Government—led by Anton Cermak, who would later become Chicago’s mayor—accused Thompson of breaking a campaign promise. The group said Thompson had signed a pledge that he wouldn’t enforce the “obsolete” state law requiring saloons to close on Sundays.30

“I may have signed it, but that doesn’t cut any figure,” Thompson said, as his train passed through Kansas. “Certain people called my attention to the violation of the Sunday closing law. The corporation counsel said it was a valid law. Heaven knows, I am no reformer. This proposition doesn’t have anything to do with whether I am wet or dry. When the corporation counsel said the law was valid, why, I had to enforce it under my oath of office. It was my absolute duty to do so.”31

“I knew it was coming sometime,” the famous First Ward alderman and saloonkeeper Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna remarked, speaking inside his crowded bar, the Workingmen’s Exchange, “so I guess the only thing to do is get loaded Saturday if you’re gonna try to last till Monday morning.”32

Kenna told a reporter: “The Sunday closing law will seriously affect about three-fourths of the saloonkeepers in the city. A large number of outlying saloons will be forced out of business.”33

The First Ward’s other alderman, Bathhouse John Coughlin, responded to the situation as he often did, with poetry:

Saloons to close on Sundays is the order of the mayor,

Prohibition soon will be statewide, ‘tis winning everywhere.

’Twill not be long, now mark my word, until this town goes dry,

Then I will quit this mundane sphere for mansions in the sky

I never dreamed that such a day would ever come to pass,

When you and I would be deprived of friendship’s social glass.

But now that Sunday’s bars are barred, this poet wants to fly

To Greenland’s icy mountains or mansions in the sky.34

Thompson’s order hurt business at the North Side’s cemetery saloons. (See Chapter 4.) Urban Koch, who had a bar at 3968 North Clark Street, said he relied on “the cemetery trade” for much of his business, as well as baseball fans attending Chicago Whales games at Weeghman Park (which would become Wrigley Field the following year, when the Cubs moved in).

“The only day there are any funerals to amount to anything is on Sunday,” Koch said. “I figure a loss of at least $500 a month to my business.”35

Beer gardens were hit especially hard, because Sundays were one of their biggest days of the week. (See Chapter 7 for more about Chicago’s large beer and amusement gardens.)

Midway Gardens, already struggling because of “a solid summer of disappointing weather,” immediately went into receivership, 36 and a judge ordered the gates padlocked.37

The owners of Bismarck Garden said they weren’t sure whether they’d be able to stay in business. 38

“It’s just a joke, it looks to me,” manager Joe Spagat said, when he first heard the news. “I don’t think he’d do it. Mayor Thompson isn’t that kind of man. He’s broad minded. They closed the saloons on Sunday in New York, but in Chicago it’s different. The people are different, yes? No, it can’t be true.”39 (Spagat later left Bismarck Gardens for a job at Green Mill Gardens.40)

Chamales said Green Mill Gardens would continue operating as usual on the other days of the week, but he wasn’t sure whether he’d be able to stay open on Sundays without the money generated by selling alcohol.

“I have a neighborhood restaurant patronage that is very encouraging,” he said, “but I do not know whether it can be developed to a point that will justify keeping open on Sunday.”41

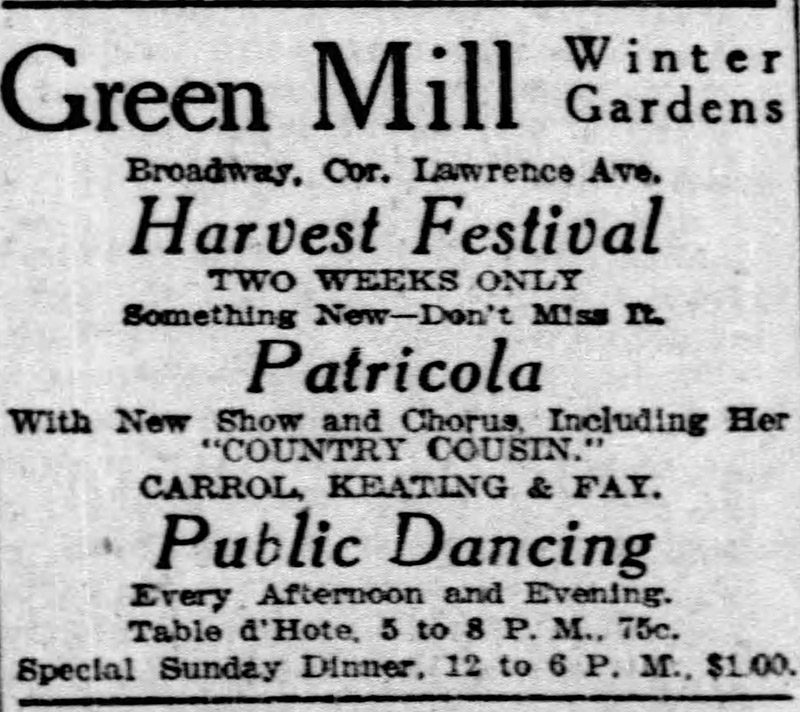

In the following months, Green Mill Gardens appeared to stay open seven days a week, advertising a “Special Sunday Dinner.” The venue had entertainment and dancing “every evening,” according to one ad.42

Mayor Thompson’s edict against Sunday booze remained in place, but reformers started complaining that the police were allowing some saloons and cabarets to operate on Sundays.

“With a great display of ire, Big Bill ordered licenses of such establishments revoked. Then, when the reformers’ indignation had cooled, the licenses were quietly restored,” Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan wrote in their book Big Bill of Chicago.

“With a great display of ire, Big Bill ordered licenses of such establishments revoked. Then, when the reformers’ indignation had cooled, the licenses were quietly restored,” Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan wrote in their book Big Bill of Chicago.

One of the South Side’s most notorious cabarets, Big Jim Colosimo’s joint, seemed to be above the law, functioning as a meeting place for prostitutes to pick up customers.

“Big Jim had his good friends in the City Hall,” Wendt and Kogan wrote. “Already he was the acknowledged overlord of prostitution in what remained of the old South Side Levee and he carried on with a minimum of police interference.”43

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 “Eastland Disaster,” Britannica, accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/Eastland-disaster.

2 “‘Tribune’ Fund Promise $25,000,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 2, 1915, 3.

3 “Chicago Circulation Wars,” Wikipedia, accessed June 9, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_circulation_wars.

4 Wayne Klatt, Chicago Journalism: A History (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2009), 83, 100.

5 1915 Chicago city directory, 120, Fold3.com.

6 “Some Show!,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 2, 1915, 3.

7 “‘Tribune’ Fund Promise $25,000,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 2, 1915, 3.

8 “‘Tribune’ Fund Nears $21,000,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 6, 1915, 5.

9 “Some Show!”; “Enough Money Received for Eastland Fund,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 3, 1915, 4.

10 “Rita Gould,” Wikipedia, accessed June 9, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rita_Gould.

11 “Rita Gould Sings Syncopated Songs With Her Hands,” St. Louis Star and Times, October 18, 1915, 6.

12 “Valli Valli,” Wikipedia, accessed June 9, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valli_Valli.

13 “Joseph Santley,” Wikipedia, accessed June 9, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Santley.

14 “Roy Atwell,” Wikipedia, accessed June 9, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Atwell.

15 “Green Mill Garden,” Chicago Daily News, July 10, 1915, 19.

16 “Ray Raymond,” IMDb, accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm4912465/; “Ray Raymond,” Find a Grave, accessed June 4, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/13023/ray-raymond; BFI, accessed June 5, 2023, https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2b7489d153.

17 “Notes of the Big League Baseball Players,” Chicago Daily News, September 15, 1915, 2. Williams’s identity: “1907 ‘A Yard of the National Game’ Chicago Cubs Panoramic Display,” Robert Edward Auctions, spring 2008, https://robertedwardauctions.com/auction/2008/spring/1133/1907-yard-national-game-chicago-cubs-panoramic-display.

18 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, December 19, 1915, Part 8, 2.

19 U.S., Passport Applications, 1921, Roll 1654, Certificate 51870; World War I draft registration card; Tami Wright family tree, accessed June 18, 2023, Ancestry.com.

20 “Dorothy Dickson,” IMDb.com, accessed June 18, 2023, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0225638/bio/?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm; “Dorothy Dickson,” Wikipedia, accessed June 18, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_Dickson; Sandra Burlingame, “Dorothy Dickson,” Jazz Standards, accessed June 18, 2023, https://www.jazzstandards.com/biographies/biography_146.htm.

21 Cook County, Illinois, U.S., Birth Certificates Index, 1871-1922; Tami Wright family tree, accessed June 18, 2023, Ancestry.com.

22 “Dorothy Hyson, 81, Actress in Britain,” New York Times, May 28, 1996, D, 15, https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/28/arts/dorothy-hyson-81-actress-in-britain.html.

23 “News of the Day Concerning Chicago,” Day Book, August 8, 1914, 7.

24 “Seek 2 Men With Burns 2 Hours Before He Died,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 22, 1914, 1.

25 Chicago Daily News, November 25, 1914, 8.

26 Day Book, July 7, 1915, 7.

27 “Sunday Saloons Closed,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1915, 1, 2.

28 “Mayor, Enroute, Talks of Order Closing Bars,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1915, 1.

29 W.A. Sunday, letter from Omaha, Nebraska, October 4, “Billy Sunday Says Thompson Decree Made Hell Howl,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1915, 2.

30 “Charge Mayor Broke Pledge,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 6, 1915, 1, 4.

31 “‘I May Have Signed Pledge, But I Must Enforce Law.’—Thompson” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 6, 1915, 1.

32 Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan, Big Bill of Chicago (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1953; Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2005), 128.

33 “Sunday Saloons Closed,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1915, 1, 2.

34 Wendt and Kogan, Big Bill, 129.

35 “Outlying Neighborhood Saloons; What Will Happen to Them?” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 6, 1915, 5.

36 “Chicago Resort Places Jolted,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 6, 1915, 4.

37 Paul Kruty, “Pleasure Garden on the Midway,” Chicago History, fall-winter 1987-88, 22.

38 “Chicago Resort Places Jolted.”

39 “Widely Varied Views Held on Closing Order,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1915, 2.

40 “Dance With Wife, $10,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 28, 1918, 11.

41 “Chicago Resort Places Jolted.”

42 Advertisements, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 17, 1915, part 8, 2; December 19, 1915, part 8, 2.

43 Wendt and Kogan, Big Bill, 132.