CHAPTER 42 of THE COOLEST SPOT IN CHICAGO:

A HISTORY OF GREEN MILL GARDENS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF UPTOWN

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

It was a big deal when Texas Guinan took over the Green Mill in December 1929. “If Prohibition had a queen, she was Texas Guinan,” Chicago Daily Tribune reporter James Doherty later recalled. And when Tex departed the Green Mill, she made the most dramatic exit, rolling to a police station in her limousine after gunshots rang out in the nightclub. It became one of the most famous episodes in the Green Mill’s history.

Before Guinan brought her act to Chicago, Doherty had seen her show at her New York City nightclub. “Guinan’s in New York was wetter than the Atlantic,” Doherty said, using “wet” as a slang term for places that served booze and people who insisted on drinking it, in spite of federal prohibition laws. “When she brought her talents to Chicago, the humidity increased locally.”

Doherty was at the Green Mill on the night when Tex made her debut in the nightclub. “It was a momentous occasion—and dripping, the night Texas Guinan opened here,” he wrote. “She was at the top then, the pride and joy of a wet country. She had been arrested in New York on charges of violating the prohibition laws, and had been acquitted. To a lot of her fans in Chicago, she had escaped the clutches of a cruel government which would have put her in prison for the kindly deed of giving a cooling drink to a feverish visitor. ‘Long live liberty and Guinan!’ was the toast at the Green Mill that opening night.”1

Guinan once described herself as follows: “I like noise, rhinestone heels, customers, plenty of attention and red velvet bathing suits. I smoke like a five-alarm fire; I eat an aspirin every night before I go to bed, I call every man I don’t know Fred and they love it, I have six uncles, I sleep on my right side and I like carrots. I eat a dozen oranges every day and I once took off 35 pounds in two weeks. I guess that settles my personality.”2

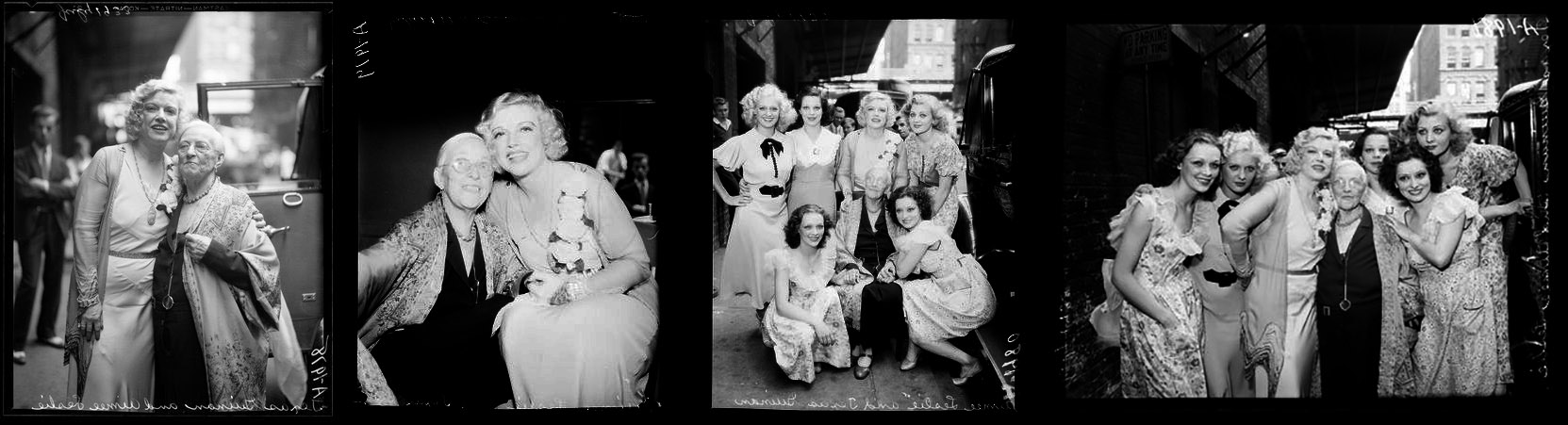

Photos of Texas Guinan in the New York Public Library archive.

“Texas” was 45 years old when she opened at the Green Mill. Mary Louis Cecelia Guinan had been born in 1884, in Waco, Texas,3 and she’d lived in Chicago for a time as a young woman.4 She later recalled performing inside Green Mill Gardens early during her career, when she was touring the country as a western cowgirl rider with the 101 Ranch Rodeo:

“I rode into the cabaret on a large white horse. The horse, not being used to the slippery dance floor, balked. To keep order I shot a few blank cartridges on the floor and guests hied for safety to the balconies. When the horse quieted down he proceeded to collect the sugar from the various tables, which did not add to the comfort of the guests who were less acquainted with the ways of horses than I. (That’s when I used horses to frighten people. Now I do it with the check.) I continued to fire stage ‘blanks’ and the police came rushing to the scene, but it all ended happily for we got the guests back to their seats, gave them a cover charge, and returned the horse to his stable.”5

This story might be true. Then again, as Louise Berliner explained in her delightful 1993 biography, Texas Guinan: Queen of the Nightclubs, Guinan and her press agents were prone to exaggeration and myth-making.

Posters for Texas Guinan movies. New York Public Library.

Guinan achieved her greatest fame as a nightclub hostess in New York City in the 1920s, doling out sassy wisecracks to the men in her audiences as she introduced the sexy young women in her troupe of dancers. Guinan astutely realized what sort of entertainment many Americans craved.

“Tex understood that restless feeling, the itchy uncomfortableness that paced through American consciousness like an anxious teenager,” Berliner wrote. “What Americans needed, judged Guinan, was a place where they could escape. So she set up her clubs, and between the hours of 10:00 P.M. and 6:00 A.M., customers were free to do as they pleased.”6

Guinan had a famous catchphrase: “Hello, suckers!” That was how she greeted the people who’d gathered in her nightclubs for some late-night and early-morning frolics. She once explained that it was her way of saying, “Hello, pal, aren’t we all alike after all?”7 On another occasion, she said: “A great many ‘suckers’ just keep on chasing the dawn. If they only waited twenty-four hours, the dawn would come back to them. Because they fail to understand that part of life, that’s why I call them ‘suckers.’”8

“Tex had a unique way with the simple expression,” Berliner wrote. “There were times when she just seemed to sing out, almost laugh out, ‘Hello, Suckers!’ It was a happy, warm greeting from one pal to another. A display of affection for humankind and all its foibles. It was also an acknowledgement of Tex’s own weaknesses. She used to say that she was the biggest sucker of them all.”9

Guinan made national headlines in 1928 when federal agents raided her New York nightclub. She went on trial in the spring of 1929 for allegedly “maintaining a public nuisance”10 and violating prohibition laws.

“Miss Guinan’s particular function was to make whoopee,” a prosecutor told the jurors. “She made everybody feel at home in a jovial way. There was entertainment, the silliest of songs and jokes and the thumbing of noses at the law. These exhibitions of whoopee were going on while the guests of the establishment were getting thoroughly in the spirit of the occasion, thanks to the liquor they had obtained.”11

The all-male jury found her not guilty.

Tex took her show on the road, arriving in Chicago that fall. Starting in mid-October, she starred in Broadway Nights at downtown’s Majestic Theatre, 22 West Monroe Street.12 She also started moonlighting: When the Majestic show ended around midnight, she would head with her “gang” over to the Club Royale, 426 South Wabash Avenue, where she entertained audiences in the early-morning hours. Chicago Daily News critic Amy Leslie was astonished at the way Guinan kept her “very faithful” fans “furiously entertained” into the wee hours. “She does things no ordinary night hostess could be caught at and she does them dashingly and well,” Leslie commented.13

Texas Guinan and her girls pose for photos with Chicago Daily News critic Amy Leslie in 1933. DN-A-1978, DN-A-1979, DN-A-1980, DN-A-1981. Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum.

On November 10, federal agents arrived at the Club Royale during one of Guinan’s shows. One of the them was holding a piece of paper. “And what’s this?” Guinan cried out.

“It’s a search warrant, and this place is going to be raided,” he said.

“O, a raid!” Guinan exclaimed. According to the Tribune, she seized “the abashed agent” by his arm and dragged him over to the piano, saying: “Listen, folks, listen. These men are prohibition agents—they won’t harm you. It’s just a raid—just a little raid. Let’s give three cheers for Uncle Sam.” As the orchestra played and Guinan led the audience in cheers, the agents went from table to table, collecting flasks and bottles.

In the end, they took only 10 pieces of evidence and made no arrests. And the nightclub’s patrons went back to dancing.14 (Two well-known figures in Chicago’s nightlife scene operated the Club Royale: Ralph Gallet, an alleged Al Capone associate who’d formerly managed the Midnight Frolics,15 and M.J. Fritzel, who’d run the Friars Inn.16)

On the same night, the feds also raided Kelly’s Stables, 431 Rush Street, and the Club Beau Monde, 519 Diversey Parkway.

“We have been watching these places for weeks, and we have evidence to show that in each cabaret the prohibition law has been violated,” said E.C. Yellowley, the regional prohibition administrator. “Ginger ale setups were served to patrons who brought their own liquor, and that has already been held sufficient to warrant permanent injunctions closing the place for one year.”17 A few weeks later, a federal judge issued temporary injunctions against the three nightclubs.18

Guinan left town, continuing her tour, but she was soon back in Chicago. On December 12, the Chicago Daily Times reported that Guinan had “purchased” the Green Mill.19 That wasn’t strictly true. Guinan and her manager, Harry O. Voiler, had a deal to run the nightclub, but Leonard Leon and Leon Sweitzer apparently continued their ownership of the Green Mill business, in a space they were leasing. They subleased the nightclub to Voiler. (Sweitzer may have been in some financial trouble at this time, according to Variety, which later reported that he “gave bouncing checks to Sophie Tucker and others.”20)

Voiler was an ex-con, who’d been imprisoned in Michigan in 1917 for armed robbery with intent to kill.21 Later, he reportedly run a black-and-tan cabaret on Chicago’s South Side.22 Now, he and his wife ran a small ticket brokerage on Randolph Street in the Loop.

“Both Voilers saw that Tex could lead them out of their small-time operation and into bigger and better things,” Berliner wrote. “They judged she would be susceptible to flattery and name-dropping, and they used both to convince her to work for them in a Chicago club.”

When Guinan was finishing up her fall tour, Voiler had followed her as she performed in Cleveland and Detroit. He wooed her with gifts and flowers.23

Doherty, the Tribune reporter, said Guinan called him for advice about the “local customs” in Chicago. “It seems she had arranged with one Harry O. Voiler to manage her affairs in Chicago,” Doherty wrote. “This was done, she indicated, because she didn’t want any trouble with the Capone gang, the Bugs Moran gang, or any other of the big bootleg combinations which might resent an outsider coming in to sell a lot of liquor.”24

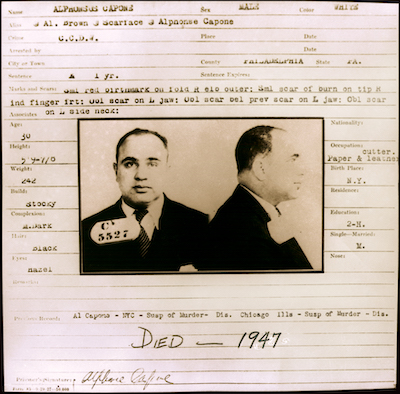

It’s not clear why Guinan thought that Voiler could help her avoid trouble with Capone, Moran, or other mobsters. As it happened, Capone wasn’t even in Chicago at this time—he was serving a year-long prison sentence in Pennsylvania for carrying a gun.

Many people suspected that Capone had engineered his own jailing, seeing prison as a safe place to hang out for a while amid gang wars and police probes. But Get Capone author Jonathan Eig wrote that Capone was simply “out of his element” when he was arrested in Philadelphia, unable to find corrupt authorities who would let him off the hook. In any case, Capone was absent from Chicago when Guinan came to town, though he was certainly still wielding power in the city.25 “His affairs seemed, indeed, to prosper,” the 1930 book Chicago Gang Wars in Pictures: X Marks the Spot commented.26

When Voiler was talking up Guinan and trying to get her to hire him, “he dropped the name Capone as if the man were his friend, and Tex began to think more seriously about his offers,” Berliner wrote. “She was attracted to the slippery Voiler.”27

Doherty wasn’t so sure that Guinan had chosen the right guy to manage her affairs in Chicago. “As a crime reporter, I knew, of course, that no one could come into Chicago to sell liquor unless he or she established diplomatic relations with the politicians and police as well as the mobs operating in that territory,” he wrote. “I didn’t know whether Voiler was the right man to represent Guinan and, anyway I wasn’t giving out that sort of advice. But I did know that I disliked the Green Mill very much at that time. It was owned by Ted Newberry then, a hoodlum who hoped to take over the throne of Al Capone. He had a couple of front men named Leonard Leon and Leon Sweitzer. ‘O, but we bought out those fellows,’ Guinan told me. ‘Why don’t you come opening night. You can sit on the piano with me.’”28

Did the Green Mill have other owners at this time, in addition to Leon and Sweitzer? Ralph Burke, who’d briefly owned the Green Mill during early 1928, was involved again in its management. The Chicagoan magazine said he was the nightclub’s head waiter, and a Green Mill ad had listed Burke’s name at the bottom.29

And another mystery man may have been on the scene. Decades later, when Berliner was working on her Guinan biography, a Chicagoan calling himself Sam Cimman got in touch with her in 1981. He said he’d been a part-owner of the Green Mill back in 1929, along with Leon and Sweitzer. But the strange thing is, I haven’t been able to find any other traces of Sam Cimman’s existence—no newspaper stories that mention him. No documents such as death certificates or Social Security records. No family trees on Ancestry.com. Nothing. Was “Sam Cimman” an alias? It’s hard to know what to believe. But Berliner’s book has all the hallmarks of a carefully researched history, complete with footnotes. Whoever Sam Cimman was, someone using that name spoke with Berliner and told a detailed story about the Green Mill’s operations in late 1929 and early 1930.

“When Tex agreed to join the Green Mill, she had asked co-owner Sam Cimman if he could lower the thirty-by-sixty-foot dance floor, which was then six inches off the floor,” Berliner wrote. “Not wanting to tear up the interior while the club was active, Cimman engineered the whole project after hours in one day. He started the workers at 5:00 A.M. Because this was the Depression, an ad placed in the Chicago Daily News requesting six carpenters brought eight hundred applicants who began lining up at 3:00 A.M. Cimman hired twelve. It was odd, recalled Cimman, that there it was, December of the first year of the Depression and they were spending thousands on a silly dance floor. Still, some people must have money. Tex rehearsed the girls while the carpenters built their stage.”30

A classified ad in the Daily News confirms this story, though it told job applicants to ask for someone named Baker.

The ad appeared in the evening paper on December 17, a mere two days before Guinan opened her show: “CARPENTERS (10)—Must be exp. on floor work. Apply after 3:30 p.m., Green Mill, 4806 Broadway. MR. BAKER.”31

The existence of this classified ad was a very obscure fact by the time Sam Cimman spoke with Berliner in 1981. As far as I can tell, no one else had written about this last-minute carpentry on the eve of Guinan’s Green Mill debut. Cimman’s knowledge of this story lends a lot of credence to the memories he shared with Berliner—even if there’s uncertainty about Cimman’s identity. And who was Mr. Baker? That’s another enigma.

According to Berliner’s book, Voiler told Guinan that he couldn’t pay his $27,000 share in the club, so she paid it for him. Guinan had a contract with Voiler, Cimman, Leon, and Sweitzer, including a guaranteed minimum of $1,500 a week plus 50 percent of the cover charges and 50 percent of the general profits.32

An ad in the Daily Times announced that Guinan would open her show on Thursday, December 19.

It referred to the Green Mill as “The Joy Spot of Chicago” and “Chicago’s Most Exclusive Club.” The ad proclaimed: “‘Texas’ (Herself), Queen of New York Night Life, and Her ‘Mob’ of Adorable Kids in the Brightest, Merriest, Happiest Show in Chicago. … You’ve Never Seen Anything Like It!”

The ad also promised: “Curfew Shall Not Ring Tonight. You May Dance Till Dawn.” 33 Chicago authorities had spent years trying to clamp down on late-night entertainment, even taking a case to the Illinois Supreme Court—City of Chicago v. Green Mill Gardens, which established that the city had the power to force the Green Mill to close at 1 a.m. But as time went on, city officials seemed to give up on that fight. Texas Guinan was in town, and if she wanted to entertain people from midnight until dawn, that was just fine.

Guinan opened her show in the middle of a snowstorm—Chicago’s worst blizzard in 11 years. Over the span of 40 hours, 14.8 inches of snow blanketed the city, and 12 deaths were blamed on the weather. Friday morning’s headline across the Tribune’s front page declared: “DRIFT-BOUND CITY DIGS OUT.”34 But the blizzard didn’t stop the festivities inside the Green Mill.35

“Thursday night, or I should say, Friday morning was the time when an event took place at the Green Mill which will be long remembered in our fair city’s garden life,” the Daily Times’ cabaret columnist reported. “For Texas Guinan took the scepter and whistle and began her rule of north-side night life.”36

Doherty did not take up Guinan on her offer to join her at the piano. But over the coming months, he attended Guinan’s shows three or four nights a week, heading to Green Mill after he’d finished his “daily crime survey” for the Tribune. He was accompanied on these outings by reporter Chesly Manly. “We both liked the atmosphere,” Doherty recalled. “We could relax. … It was restful at Guinan’s. It was educational. It was pleasant.”37

Green Mill advertisements told Chicagoans that this was one show they simply had to see: “If you never shaken a rattle with TEXAS GUINAN—whooped up a big hand for this little girl—you’ve missed SOMETHING. If you have—well, then, we need not add a word, except that the girl who has made the country laugh is now at the Green Mill with her famous ‘gang.’”38

Meanwhile, the Daily Times’ cabaret column continued to promote the show: “Tex Guinan is holding up The Green Mill like it has never been before (and this is no pun). Her ‘gang’ is all that she says it is, to wit, ‘adorable’; the music is good, the dancing fun, the eats okay, and Tex—well, Tex is Tex, and that is a whole story in one word. She has no equal in her line.”39

Later in the month, the column offered more hype: “Texas Guinan (give the little girl a nice big hand) has been making the lights in the Green Mill twinkle brighter since she took charge of festivities. There is nobody quite like Texas. She has the gift of making everyone feel at home and the ‘whoopee’ she produces is the kind you don’t forget in a hurry. Texas has a lot of good entertainers besides her own sparkling self. Kitty O’Reilly, Jean O’Reilly, Lorraine Hayes, Norma Taylor and the sparkling music of Austin Mack’s orchestra are more reasons why the Green Mill is the place to enjoy yourself.”40

Harold L. Buckley, a 22-year-old from Ohio, offered this testimonial to a Daily Times reporter: “Say, Tex Guinan had my number in the first act. ‘Hello, sucker!’ she says to me the very first night I showed up at the Green Mill. But I guess she was right, at that.”

The reporter was interviewing Buckley, the son of a minister, because he’d been arrested on a charge of kiting $91.60 in false checks. “He speaks glibly of his misadventure,” the Times reported. “He is a young man in the modern manner. Spats and flaring lapels, a color ensemble in cravat and handkerchief.”

“Night clubs—they’re my weakness,” Buckley said. “And if you think they don’t know me—say! I couldn’t keep the hostesses away from me. It was like that everywhere I went—Colosimo’s, the Frolics, the Beau Monde, Green Mill. But I played no favorites. I’ve a mamma of my own. And how! … Just a minister’s son gone wrong. Dad doesn’t approve of his wayward boy. I made too much whoopee at home New Year’s Eve. But, of course, a small town isn’t the place for me. I crave the bright lights, believe me.”41

Lucia Lewis, a writer for the Chicagoan magazine, described Guinan making a raucous entrance during one of her Green Mill shows: “Oompah—oompah—oomp! The smooth rhythm of the orchestral jazz is broken by the shriek of a police whistle. Fire gongs clang in the startled air. The crowd pauses, suddenly hushed, as a woman makes her way through the tables, and then as suddenly beats itself into frenzy with a hundred wooden clappers. Texas is on—to the noise that has greeted her so many thousands of nights that not even she can count them.”

Even skeptics and newcomers found themselves entranced by Guinan’s wisecracks and her “large good-natured grin.” When Guinan urged them, “Come on, give this little girl a hand,” they clapped wildly. Lewis observed:

So Texas Guinan fastens another scalp to her belt. She has been annexing scalps for a long time now. Such amazing scalps are they, and so firmly are they annexed that Texas becomes more than the hostess of an ephemeral night club. She looms on the national scene, the perfect exemplar of the rather lovable rowdyism, the boisterous fun-making, the broad humor and practical joking that seem typically American, virile, with the tang of the pioneer days. Though this be blasphemy, we feel somehow that Abe Lincoln would have enjoyed swapping jokes with Texas. Laugh if you will, but I offer with a patriotic flourish: Texas Guinan—American!

Her powerful voice shouts witticisms impudently at all who come. Butter and egg men, Colonel Lindbergh, the Prince of Wales, Queen Marie, minions of the law—the more awesome the personage the less awed is Texas. Unchastened by her experiences in eastern courts she tosses quips at a local judge, spotted at one of the Green Mill tables.

“Let’s give Judge …………… a hand. Glad to see you. It always makes me feel better to have a good judge in the house.”

She invites him insistently to a chair at her side and, as he self-consciously settles into it, turns on a battery hidden under the seat. The law leaps into the air in perfect Mack Sennett fashion. To a native eye slightly overnourished on imported subtleties and overwhelmed by dictatorial traffic police the sight of this pompous gentleman in the air is worth the cover charge. But Texas’ big achievement is the fact that the pompous gentlemen like it and come back for more.

Although Guinan’s show featured young women in sexy outfits, Lewis thought it was all “surprisingly decent.” Most of the attention was focused on Guinan and her jokes rather than the dancers who came and went from the stage. Introducing one of these young performers, Guinan remarked: “This little girl would make some man a good wife. She hasn’t a bad thought in her head. And nothing else either.” If anyone in the audience displayed any “amorous tendencies,” Guinan called them out, chiding: “Here, here. Don’t you give my place a bad name. I’ll tend to that.”

When the show finally came to an end as dawn approached, Guinan rallied the audience members to join together in song. “A screen is rolled across the floor and words are flashed upon it,” Lewis wrote. “Into the night pour the strains of ‘Sweet Adeline,’ ‘In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree,’ ‘When You and I Were Young Maggie,’ ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ and one resounding college song after another. It all seems pretty silly later, in the solemn moments of the day, but for an hour or two the years do roll back and our voices sound as we always knew they would if we only had a chance. Which, Miss Guinan, is something of an achievement.”42

Guinan responded to Lewis’s article with a letter to the editor, commenting, “Chicago is always kind to me and my present visit is happier than ever.” Guinan also made a joke about the city’s notorious gang violence: “I understand the shooting is to help the overcrowded hotel situation.” And then she asked, “Would you like to have me recite?” before closing her letter with a bit of verse:

When I came out to Chicago I heard a lot of talk,

About the hard-boiled gangsters who make you walk the chalk;

Now one of these real he-men, I would really like to get,

For I look beneath my bed each night, and haven’t found one yet.

IT’S A LIE!

Yours yesterday, today, and tomorrow—

Texas Guinan43

Guinan penned that letter, joking about Chicago’s “hard-boiled gangsters,” a month after the Green Mill was connected with an episode of deadly gang violence.

Joseph Cada, 29, a reputed gangster nicknamed “Motor Joe,” visited the Green Mill after midnight on February 2, 1930, taking in one of Guinan’s shows. The Tribune reported that he “was known in gangdom as a fop and an expert automobile driver and mechanic at one time affiliated with beer runners of the Druggan and Lake syndicate.” That morning, Cada left the Green Mill with two men. At 5:45 a.m., they were riding together in Cada’s “expensive automobile” when the other two guys fired five bullets into Cada at the intersection of Broadway and Leland Avenue, roughly one block from the Green Mill.44

Chicago Gang Wars in Pictures: X Marks the Spot suggested that Cada’s death may have something to do with an earlier incident in Chicago’s gang wars: Cada had been present when a beer runner named James Walsh was killed several weeks earlier.45 Like nearly all of Chicago’s gang killings during the Prohibition Era, the slaying of Motor Joe was never solved.

Was Guinan herself the target of a criminal plot involving Cada? On March 3, the Daily Times dished out these gossipy details: “This probably will be denied, but the state’s attorney’s office knows it to be true: On the night of Feb. 2, when ‘Motor Joe’ Cada was murdered, he was on his way to the Green Mill to meet a group of henchmen, who were making plans to kidnap Texas Guinan.”46 That may have been nothing more than rumor or speculation, but the report surely must have alarmed Guinan.

Around this time, Guinan began feeling uneasy about her situation in Chicago, according to Berliner’s biography. “As time passed, Tex began to miss New York and grew more and more uneasy about guns that kept appearing at her club,” Berliner wrote. “The Green Mill rapidly gained a reputation as a gangster hangout and folks assumed Tex had an ‘in’ with the underworld. … She realized now that she had affiliated herself with the wrong kind of crowd.”47

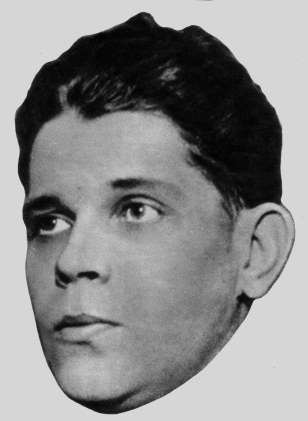

That crowd included a tall handsome man48 with “blond” wavy hair49 who gave his name as Louis V. Bader.50 (His hair does not look that blond in newspaper photos, however.) Nicknamed Buster, he was employed by the Green Mill as a “heavy man.” He didn’t like being called a bouncer, but that’s essentially what he was.51

The young women in Texas Guinan’s troupe took a liking to Buster. “He was so quiet and conservative and home-loving,” said Tina Tweedie, a 21-year-old entertainer described by the Daily Times as “a stunning blonde.”

“So often he spoke of his mother, and didn’t seem to care at all about girls,” Tweedie continued. “We liked him a lot—all of his girls. He was so accommodating. If we didn’t have anyone to see us home, he’d do it. Why, I never have seen him take a drink, which is unusual with modern young men. He is a wonderful dancer—I’ve danced with him frequently at the Green Mill, but he never took me or any of the other girls out. In fact, he was always alone, never associated with racketeers or such people. Buster—we all called him that—doesn’t have any earmarks of the gangster. He’s a real gentleman.”52

As it turned out, Buster’s real name was Leo V. Brothers (or Vincent Langford Brothers). The 28-year-old53 had reportedly been arrested more than 50 times in St. Louis—accused of robbery, auto theft, firing guns, throwing stench bombs, and blowing up a laundry truck—but he’d never been convicted. Described by newspapers as a “labor organizer,” a “bombing chauffeur,” an “extortionist,” and a “red hot,” Brothers had disappeared from St. Louis in August 1929, when a coroner’s jury accused him of killing a service car driver who’d quit his union membership.54

Brothers was friendly with a Missouri gang called Egan’s Rats.55 And his pals included Pat Hogan, a St. Louis hoodlum in his mid-20s who’d reportedly been arrested numerous times for murder and other crimes across the Midwest, as he used various aliases: Paddy O’Day, Patrick Courtney, Larry Murray, Larry Wahl, and John Baker.

The Tribune reported that Hogan was a “gang associate” of Ted Newberry—the North Side mobster who was reportedly the real power behind the Green Mill—and Newberry’s henchman Bennie Bennett. In late 1929, Hogan was in Chicago, working as a “heavy man” at the Green Mill.56

Brothers followed Hogan to Chicago, asking Harry Voiler for a job at the Green Mill. “I told him I was sent up there,” Brothers later recalled, when he was questioned by prosecutors. “I mentioned Paddy Hogan’s name. … He said, ‘All right, come out.’” 57 Investigators later said that Newberry recommended Brothers for the job.58

While Brothers was working at the Green Mill, he was rooming in the South Side’s Kenwood neighborhood.59 Investigators later questioned Brothers about what sort of work Voiler had him do:

Q: What did he tell you to do?

A: To turn on the spotlight and when people came in to sit people at the tables.

Q: What do you mean by sitting people around the tables?

A: Like if there would be people quarreling or getting in a quarrel or anything, move the tables over or move another party in between them; keep order in the house, that is all.

Q: You were a policeman, were you?

A: No, just to keep order.

Q: Bouncer?

A: No.

Q: What would you call the job you had up there?

A: Bouncer, whatever you would call it. I never had any trouble.

Q: Heavy man, is that what you call them?

A: Maybe so, I don’t know.

Q: Suppose you saw trouble, what did he tell you to do?

A: The only trouble, people drink, you tell them to sit down, and they sit down.

Q: Suppose they got to fighting?

A: The majority of them, they were too drunk to hurt anybody.

Q: How much did you get a week there?

A: $100 a week.60

According to Berliner’s book, Voiler hired Brothers to serve as Guinan’s bodyguard, keeping an eye on her and escorting her around the city. Guinan’s publicist, John Stein, said that Brothers saved her from a kidnapping attempt.61

At some point during Guinan’s time at the Green Mill, the nightclub received a tip that St. Louis gangsters were plotting a holdup at the cabaret, with plans to rob the guests as well as the management. According to investigators, the Green Mill’s managers brought in members of the North Side gang, armed with machine guns, to defend the joint against any attack on the night of the expected robbery. Seeing these preparations, Buster said he was feeling ill and left. Investigators later concluded that he was part of the robbery plot—and that he’d slipped away to warn his friends not to go through with it.62

This wasn’t the only disturbing development at the Green Mill: Stories circulated that some of the nightclub’s patrons had been beaten up, for no apparent reason.63

Brothers later told a newspaper reporter that he’d never seen Bugs Moran or any other gangster at the Green Mill. “I never knew any of those fellows,” he said. “I do know, though, if they appeared, three coppers on duty would have grabbed them, because Tex was pretty strict, and besides she wouldn’t lay herself open to any rough stuff.”64

A blues singer reportedly began an affair with a gangster she ran into at the Green Mill during Guinan’s reign. “She sang those sort of songs drunks like to listen to; her voice was deep and throaty with a tear always in it,” the Chicago Sun reported years later. The gangster was “a big good-looking blackhaired man who just swept her off her feet.” The Sun article did not reveal either person’s name, but it included enough details to make it clear who this gangster was: Ted Newberry.

“When she finally found out what he was, and that he was a married man, it was too late,” the Sun reported, describing the gangster’s rough treatment of his blues-singing mistress. “… more than once she had to paint out her black eyes so the night club customers wouldn’t notice. His wife knew all about what was going on but there was nothing she could do about it; she had her troubles too.”65

Early on the morning of March 10, Buster left the Green Mill with Dorothy Wahl, a 19-year-old chorus girl in Guinan’s ensemble, and two young men who’d been “making merry.” They all went for a ride, reportedly stealing the car of a Green Mill patron. As they sped down Sheridan Road around 5 a.m., they were chased by the Lincoln Park Commission’s police force (which had jurisdiction over park boulevards, including Sheridan Road). The police chased them for miles, firing four shots at the fleeing car. The speeders, who were going as fast as 60 miles an hour, fired two shots back at the cops. After narrowly missing a collision with a streetcar, the “joy riders” crashed their car into a curb in front of the Morrison Hotel, at Madison and Clark Streets in the Loop. Police found a box of shotgun shells in the car, and a revolver on the running board. The car’s occupants all denied owning the gun. “From the incoherent statements of those seized, the police learned the ride was a continuation of a party in the Green Mill,” the Daily News reported.66

One of the men in the car was Bernard McMahon, who’d made headlines six years earlier for a similar police chase. The Daily Worker, a communist newspaper, had called him the “pleasure-seeking parasite” son of a millionaire,67 while a police official remarked: “Just a sample of what this ultra modern life is doing for our rich men’s sons.”68 McMahon was arrested again after this latest car chase, along with George Banahan and “Louis Bader,” but the police released Dorothy Wahl.69 The man who’d given his name as Louis Bader never showed up for his trial. But one of the cops involved in the chase later identified him as Leo Brothers.70

A week or so after her escapade in the speeding car, Dorothy Wahl got into a fight at the Green Mill. One of the girls who allegedly attacked her was Kitty O’Reilly, who’d been described by the Chicagoan magazine as the most charismatic girl in Guinan’s troupe. “The little O’Reilly is a fetching piece of Ireland,” Lucia Lewis wrote. “… Minute, auburn-haired and blue-eyed, with a more delightfully ‘micky’ and impudent face than these eyes have ever encountered, Kitty taps nonchalantly through the acts, stoops to tie a shoelace without a trace of nervousness because she is holding up the show, thumbs her nose at the ‘fresh guys’ and hurries away to early mass. (We have it on good authority that she really does, too.)”71

Lorraine Hayes. From left: New York Daily News, March 24, 1930; Chicago Daily Times, March 24, 1930; Waxahachie Daily Light, March 27, 1930.

The other girl feuding with Wahl was Lorraine Hayes, who just happened to be the sweetheart of former Green Mill boss Leon Sweitzer. The Herald and Examiner called her “an attractive brunette,”72 while the New York Daily News said she was blonde and “a peppy little kid of 19.”73

Hayes and O’Reilly accused Wahl of “winning” other girls’ boyfriends, the Tribune later reported. “In the number where the girls wore Mexican togs and brandished cap pistols, Miss Wahl was hit on the head by two of the metal toy guns.”74 The New York Daily News described it as “a small riot on the floor” of the Green Mill. “In a military number two of the Guinan girls jumped on a third and beat her up with their toy guns,” the newspaper reported. “The patrons cheered and Guinan ran out on the floor, trying to separate them, but had to retire and call the bouncers.” Guinan fired Hayes and O’Reilly.75

Guinan’s parents didn’t seem to sense anything was amiss when they visited Chicago in March. “She has done a fine business but spends money like a Drunken Sailor on strangers,” her father, Mike, wrote in a letter to Guinan’s sister Pearl. “… Tex had so many places to go and of course we have a nice room at the Sherman House.”76

But Guinan was making plans to cut off her engagement at the Green Mill at the end of March—a month earlier than scheduled. “When she told the owners of the Green Mill that she had plans to leave, they tried to stall her,” Berliner wrote. “Tex was worth a tremendous amount of money to them.”77

Tribune reporter James Doherty was asking questions that made Guinan nervous. He wanted to know: What had happened to Ted Newberry? No one had seen the Green Mill’s putative mob boss since sometime around mid-January. There was speculation that he may have been killed.

“I thought Texas was terrific, but, at the same time, I got to be very much annoyed with her,” Doherty recalled. “She wouldn’t tell me the truth about the story I wanted to break. Business was booming at the Green Mill with the arrival of Guinan. At the same time, plots were being plotted and counterplots counterplotted. Something had happened to Ted Newberry, the ambitious hoodlum. He had disappeared. There were rumors about things that were happening in gangland. I wanted to find Newberry.”78

Newberry had vanished a little more than a month after someone tried to kill him. On the night of November 30—around the time when Sophie Tucker was giving her final show at the Green Mill—Newberry was wounded in a drive-by shooting outside one of the Bugs Moran gang’s main hangouts, the Wigwam Café at 3750 Broadway. Clipped on the wrist by a bullet, he’d escaped serious injury.79

Meanwhile, Doherty noticed that the Green Mill’s previous owners, Leon Sweitzer and Leonard Leon, were still showing up at the nightclub. “I learned that Texas Guinan had not been entirely truthful when she said she had bought out Sweitzer and Leon, the ostensible owners of the Green Mill,” he said. “They were still hanging around. And I was sure Ted Newberry was back of them.”

One night, Doherty asked Guinan, “Have you been in touch with Newberry lately?” Doherty later recalled how Guinan “flared up,” telling him he had no right to ask her such a question. “If I knew, I wouldn’t tell you,” she said.

Doherty also tried to get Voiler to talk. “Where’s Newberry keeping himself these days?” he said. Voiler snarled back, “You ought to know better than to ask a question like that.”

“That convinced me there was blood on the moon,” Doherty later recalled.80

On March 17, the Tribune reported that Ted Newberry had fled to Toronto because he feared for his life—he’d discovered a vacant flat where three machine guns were aimed at his apartment on Pine Grove Avenue. (There was no byline on this Tribune story, but it may well have been written by Doherty.) The Daily Times had a similar story, but it reported that machine guns were found aimed at Newberry’s headquarters in the Wigwam Cafe.

This news came out as the body of Newberry’s bodyguard and chauffeur, John “The Billiken” Rito, was discovered in the Chicago River’s North Branch. Just south of the bridge at Irving Park Road, a man was walking his dog when he found the glassy-eyed corpse floating face up. Rito had been beaten, tortured, stabbed, shot, and tied to a rock. It was believed that he’d been dead for two weeks. “The arms were fastened across his breast as if in religious worship,” the Daily Times reported. “A prayer book was found in his pockets. … The words, ‘One of you is about to betray me,’ were underlined in Rito’s prayerbook.”

It’s unknown why Rito was nicknamed “The Billiken,” but it may have been a reference to a charm doll manufactured by the Billiken Company of Chicago—a monkey-like figure with pointed ears, a mischievous smile, and a tuft of hair atop a pointy head.81

Rito had previously been a henchman for Capone—he even wore one of the diamond-studded belts that Capone awarded to his most trusted men. But then, Rito had switched sides to work with Newberry in Bugs Moran’s North Side gang, where he’d become the “chief collector.” According to the Times, police detectives believed that Rito was a “double-crosser” who’d held out on “alky returns” to Newberry, keeping some of the booze money for himself. “People don’t double-cross Mr. Newberry with impunity,” the Times commented.82 But this theory had one big hole in it: At the time of Rito’s killing, Newberry was supposedly hiding out in Canada. Would he have been able to engineer Rito’s death from afar? The Times suggested another possibility: Perhaps it was Capone and his mob who’d killed Rito for double-crossing them.

But the Tribune soon reported that detectives believed the true culprits were the Aiello brothers, a gang allied with Moran’s North Side mob. The police believed that the Aiellos had also killed Bennie Bennett, a “Newberry man” who’d worked closely with Rito.

Bennett hadn’t been seen for six weeks, and the Tribune reported that he’d “gone for the sort of ride from which none return.”83 Shortly before Bennett vanished, he’d reportedly argued with Bugs Moran over a whisky deal, exchanging blows with the mob boss.84 Bennett was never found; investigators believed he was one of several slain mobsters whose bodies were burned up in a crematory by the Aiello and Moran gangs.85

Which side of these conflicts was Ted Newberry on? Was he part of the operation to kill his own henchmen, Rito and Bennett, or was he being targeted alongside them? And who was trying to kill Newberry before he went into hiding? The Tribune reported that a police official was describing the situation as “the recent break-up of the north side gang in which Bugs Moran and Ted Newberry shared leadership.”86 The implication was clear: Newberry was no longer allied with Moran.

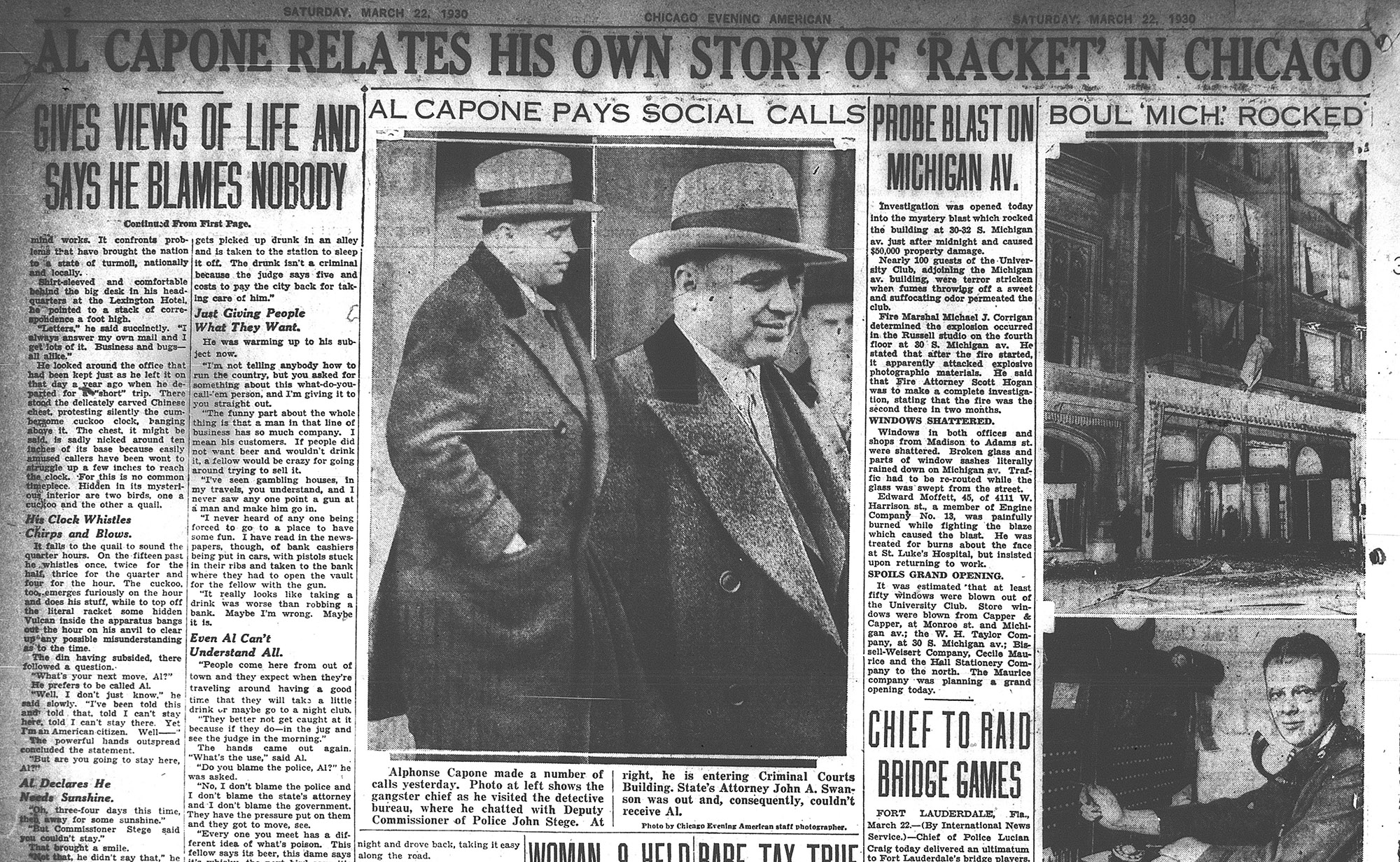

Al Capone was released from the Eastern Penitentiary in Pennsylvania on March 17—the same day when newspapers reported about Newberry’s flight to Canada and the discovery of the Billiken’s corpse.87 Capone was back in Chicago on March 22, when a reporter for the Chicago Evening American interviewed him at his headquarters in the Lexington Hotel. “You’re supposed to be king of the racketeers,” the reporter remarked.

“I suppose so, but am I? Listen to this,” Capone said. “I have a little money invested in several enterprises that you or the police or the reformers would call strictly ‘legit.’ I’m not going to say what they are. There’s enough heat about me now without sending a lot of people poking into my private affairs.”

Capone insisted that he was providing services that people wanted. “I never heard of anyone being forced to go to a place to have some fun,” he said. “… It really looks like taking a drink was worse than robbing a bank. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe it is. People come here from out of town and they expect when they’re traveling around having a good time that they will take a little drink or maybe go to a nightclub. They better not get caught at it because if they do—in the jug and see the judge in the morning.”88

That very same night, people gathered to have a good time in the Green Mill. It was a Saturday night, and once again, Texas Guinan was putting on a good show.

As the night turned into morning, Leon Sweitzer showed up. The former Green Mill boss was there to collect money. He’d started a new cabaret, the Little Club, at 975 North State Street—where an unexploded bomb had been found at the rear of the building a week earlier.89 “Sweitzer long has been regarded as ‘on the spot’ by those who know about such things here,” the New York Daily News later commented,90 using a slang term that meant “marked for death.”

Even as he ran the Little Club, Sweitzer continued getting rent from Harry Voiler, who’d agreed to use the Green Mill for Guinan’s show and pay rent through May 1. But now, Sweitzer had heard about Guinan’s plans for a premature exit.

Sweitzer spent that evening with his sweetheart, Lorraine Hayes, one of those feuding chorus girls recently fired by Guinan. “I took Lorraine to the theater Saturday night and then to the Little Club,” Sweitzer recalled. “About 3:15 Sunday morning we drove to the Green Mill. I took along Solly Marks, who used to be doorman at the Mill and now works for us at the Little Club.”91

Sweitzer reportedly told his companions, “Just wait in the car for me. I’ll only be a minute. I’ve got to see Voiler about the rent.”92 Here’s how Sweitzer described the events to assistant state’s attorney Abraham Marovitz:

“They stayed in the car while I went in to talk to Voiler. Voiler and I were sitting at a table near the entrance. I told him I heard Guinan was leaving next week and Voiler said that was true. I told him he owed me $2,000 now and he would have to pay the rent until May 1, even though he did close the place. He told me I wouldn’t get a dime, and I said I’d have to come and take the receipts.”93

Voiler’s bodyguard, Arthur D. Reed, came over. The Chicago Herald and Examiner described Reed as an “alumnus of Leavenworth penitentiary, San Quentin, Folsom and numerous other penal institutions.” 94 Prosecutors later said he’d served prison sentences for robbery and violating the Mann Act. He’d been hired by Voiler just two days after he’d been released from his most recent stint in prison.95

“Then this Art Reed came to the table and asked me if I thought I could push them around,” Sweitzer recalled. “I said I wanted what was coming to me, and Reed and another man, whose name I didn’t know, each hit me on the head with a gun. Then they told me to get back against the wall, and all three of them had guns pointed at me and they ordered me to walk upstairs to the office, which I did.”96

Or, as Variety’s report put it: “cold steel was shoved into his back and he was marched upstairs.”97

At this time, the Green Mill was a two-story-high space, with a second-floor balcony. According to Sweitzer, a business office was upstairs, “on the mezzanine floor.”98

After they all walked into the office, “Reed told me to kneel down,” Sweitzer recalled. “I wouldn’t do it, and he shot me in the leg. I turned to run, and both Voiler and the third man fired at me but I kept running.”99

Variety used “Chicago” as a verb when it described this moment: “When he made a break his captors started Chicagoing, three bullets taking effect.”100

One bullet hit Sweitzer in the left chest, deflected by a rib; another hit his arm; and a third pierced his leg. Sweitzer heard someone say: “So you’re tough, eh?”

“I started outside, followed by someone,” Sweitzer said. “I think he intended to finish me. Voiler and Reed were two of the three that shot me. I recognized the other, too, but vaguely, so I can’t name him.” 101

At this moment on the stage, Guinan “was asking the suckers to give the little girl a big hand when Leon Sweitzer … ran down a stairway from a balcony pursued by two men shooting at him,” the Tribune reported.102

According to the New York Daily News: “Guinan and her ‘twenty darlings’ … were pelting 800 suckers with cotton snowballs. The orchestra was going full blast; Tex was shouting at the top of her voice, and amid the general din the argument between the managers went unnoticed.”103

Waiting outside in the car, Sweitzer’s sweetheart had grown worried. According to various reports, she either sent Solly Marks into the nightclub to check out the situation or went inside herself.

“Down in the lobby,” Sweitzer recalled, “Lorraine had just come in to see what had kept me so long, and she and Marks helped me into the car and took me to the hospital.”104

The Herald and Examiner reported that the Green Mill audience was barely even aware of the shooting: “The shooting did not itself interrupt the merriment. ‘Tex’ Guinan, queen of the sun dodgers’ cult, continued as hostess to exhort the ‘suckers’ to enjoy themselves at triple prices. The orchestra bleated on. Some 800 patrons, few realizing the gravity of the situation, swayed about the tables. Waiters hurried here and there with ginger-ale and fancy checks.”105

In contrast, the Tribune initially reported that the shooting sparked a panic: “A thousand other guests, enjoying the entertainment provided by Hostess Texas Guinan, dashed in a mad melée for the exits when the bullets began to fly and Sweitzer slumped to the floor with wounds in the lung, arm and leg.”106 But in a later story, the Tribune downplayed the supposed panic: “The band kept playing and Tex continued her wise cracking and cheer leading while policemen rushed in and seized Voiler and Reed. Then they closed the show.”107

Lieutenant William Lang of the Summerdale police station arrived at the Green Mill a few minutes after the shooting, quickly arresting Voiler and Reed.108 The police were unable to identify the third man involved in the shooting, and they couldn’t find any guns—except for a revolver someone had handed to Alfred E. Kahn, an employee of the city collector’s office who was in the crowd. In the chaotic moments after the shooting, a man running through the nightclub had given the gun to Kahn, who was unable to describe the man.109

Voiler and Reed denied firing any shots. Voiler told the police Sweitzer had entered the cabaret and demanded payment, threatening to seize money from the cash register. Voiler said he wasn’t present when the shots were fired.110

At the Summerdale police station, Voiler and Reed were booked on charges of assault and attempted murder. Texas Guinan soon arrived, “adorned in fine furs, a costly evening gown and agleam with jewels, lolling back in a Rolls-Royce, driven by a liveried chauffeur,” the Herald and Examiner reported. As Guinan entered the station, she told the cops: “I’ve got the Rolls. Who’s got coffee?”

Guinan tried to bail out Voiler, telling the police he was “a wonderful man,” but they spurned all of her pleas.111 “He’s so nice. I know he wouldn’t shoot anybody,” Guinan reportedly “cooed.”112 She telephoned a number of people with political influence and asked for help, all to no avail. Lorraine Hayes was also at the police station, loudly insisting that the cops shouldn’t release the man who’d shot her boyfriend. Over and over, she cried out: “Voiler shot him! Keep him in jail!”113

Guinan told the police she didn’t know anything about the shooting. She noted that the shooting had happened upstairs, followed by some action in the nightclub’s lobby—in areas that couldn’t be seen from the stage.

“This is my first record at this police station,” she cracked. “I usually make them for the talking machine people.” She sat down at a typewriter and offered to type her own statement, but the police declined her offer. She also invited the policemen to have dinner with her at a hotel in the Loop.114 Concluding their talk, a cop asked Guinan: “Where can we reach you, after you leave here?”

“Any courtroom, New York City,” she said. And then, as she walked out of the police station, she remarked, “I certainly closed with a bang, didn’t I?”115

Guinan had been planning a gala farewell party on the following Saturday, but now there was no reason for her to stick around that long. Deputy police commissioner Thomas Wolfe told her that he’d permanently shut down the Green Mill.116 Authorities also closed the Little Club, Sweitzer’s cabaret on State Street, “on a charge of notoriety.”117

Was the shooting at the Green Mill simply a dispute over money? Sweitzer seemed to believe it was more than that. He suggested that the shooting had something to do with Al Capone’s return to Chicago.

“It’s terrible,” Sweitzer said at the Lake View Hospital, speaking with Lang. “It’s got so that a businessman can’t do business without a lot of hoodlums throwing slugs at him. I don’t propose to throw any slugs back at them. I propose to prosecute. Ever since Al came back the boys are hysterical. They’ve gone nuts. They think they’re running the town. They’re all throwing slugs. I am a businessman. I went to this place on a legitimate business errand. Money was due me and when I asked for it, I got a rain of slugs. If I hadn’t busted through the door and dived downstairs I’d have been killed. I’m a nightclub operator, but that’s a legitimate business. No one was ever hurt in any of my clubs. These guys knew I wasn’t armed and they tried to kill me in cold blood.”118

Was Sweitzer saying that Capone’s return had created an atmosphere of lawlessness in Chicago? Or was he implying that Voiler was directly connected with Capone?

Meanwhile, police officials noted that Ted Newberry was “a friend of Sweitzer.”119 This seemed to confirm Doherty’s reporting about Newberry’s connections to the Green Mill. Abraham Marovitz, the assistant state’s attorney who took a statement from Sweitzer at the hospital, suggested that the shooting had something to do with Newberry, though he was vague about what it all meant.

“Sweitzer said the shooting was over money,” Marovitz told the Tribune. “It probably was, but the disappearance of Ted Newberry, the recent murder of John ‘Billiken’ Rito, alias Russo, one of Newberry’s men, and the supposed murder of another of Newberry’s crew may have been contributing causes. Also the recent beatings administered to a couple of the patrons of the Green Mill and the finding of a large quantity of dynamite at the rear entrance of the Little Club are events connected with this shooting.”120

It’s also possible that Sweitzer’s romance with Lorraine Hayes may have been a factor in the shooting. That’s what Guinan suggested when she spoke with Daily Times writer Tom Killian (after refusing to discuss the shooting with other newspapers).

“What I mean, y’understand, this Green Mill shooting is a little bunch of hooey!” Guinan said. “You mean what I mean? Just a rag and a bone and a hank of hair, you understand? That’s from that poetry fellow—I think he also invented that one about ‘green-eyed jealousy.’ Sure! You know what I mean?”

Sighing, Guinan continued: “Money and a woman. Y’understand? They’ll always cause trouble. Lord knows, I’d ought to know!—I’ve caused enough myself! We opened at the Green Mill 14 weeks ago. We’ve done $143,000 worth of business there since. This fellow Sweitzer was a flop and he got jealous. He had subleased the place to Mr. Voiler, a perfect gentleman if I do say so.

“Lorraine Hayes was one of my children—just a sweet little entertainer easing the nerves of the tired businessmen. Why, she could say ‘Hello, sucker’ almost like me. Can y’imagine? And then she goes and falls for this guy Sweitzer and she starts trouble among my little children. And then Voiler lays her off for a few days and Saturday night they come in, and she’s egged him on. Y’understand? The woman angle, see? So I’d said that I was going to quit and take my infants back to New York, see? And Sweitzer was sore because he was afraid for his rent. Y’understand?”121

In another interview, Guinan told the American that she hoped to return to Chicago as soon as possible. “I like Chicago and I guess Chicagoans like me or they wouldn’t have given me $143,000 in 14 weeks,” she said. “The only wrong thing about Chicago is that the men ask you out to dinner—and want to stay for breakfast. But I’ll be back here. …

“You know, I’m crazy about Chicago. Everyone is so nice to me here. … There’s a real Broadway in Chicago. The people make Chicago’s Broadway—the Broadway doesn’t make the people. You know, Chicago can’t be so bad, in spite of all one hears about it. Nobody ever tried to take me for a ride, and I’d be an easy victim.”122

When Guinan arrived in New York City, stepping off a train on March 30, reporters greeted her with questions. “Have I any plans?” she said, fingering her coat’s leopard fur collar. “Say young man, I’ve got more plans than an architect.”123 Later in the week, she told reporters: “This town has gone to hell in the six months since I’ve been away. … If you don’t carry a .44 gun out there they think you’re odd.”124

An editorial in the Chicagoan lamented Guinan’s absence from the Windy City:

That big, breezy, wholesome girl, Miss Texas Guinan, has left us, and things are comparatively quiet on the whoopee trail. Our resemblance to a cow-town on Saturday night has vanished, and the wild jackass no longer brays at the moonshine. The goggle-eyed sucker misses the baited hook, and the boop-a-doop bird yearns sadly for that little girl on the end who has gone away from here. My God, how silent the nights are getting!

The racket was wearing thin at the old Green Mill. The takings had fallen off to such an extent that Miss Guinan decided to shorten the contract and observe Holy Week. Then something exploded, and the police kicked the joint over. … Well, anyway they can’t say that Tex didn’t close with a bang.125

As prosecutors began their case, Marovitz told a judge about Voiler’s criminal record, noting that he was wanted for robbery in Cincinnati. “We’re prepared to bring him to justice at last—he and his man, Reed, whom he hired two days after Reed’s second release from a penitentiary,” Marovitz said.126

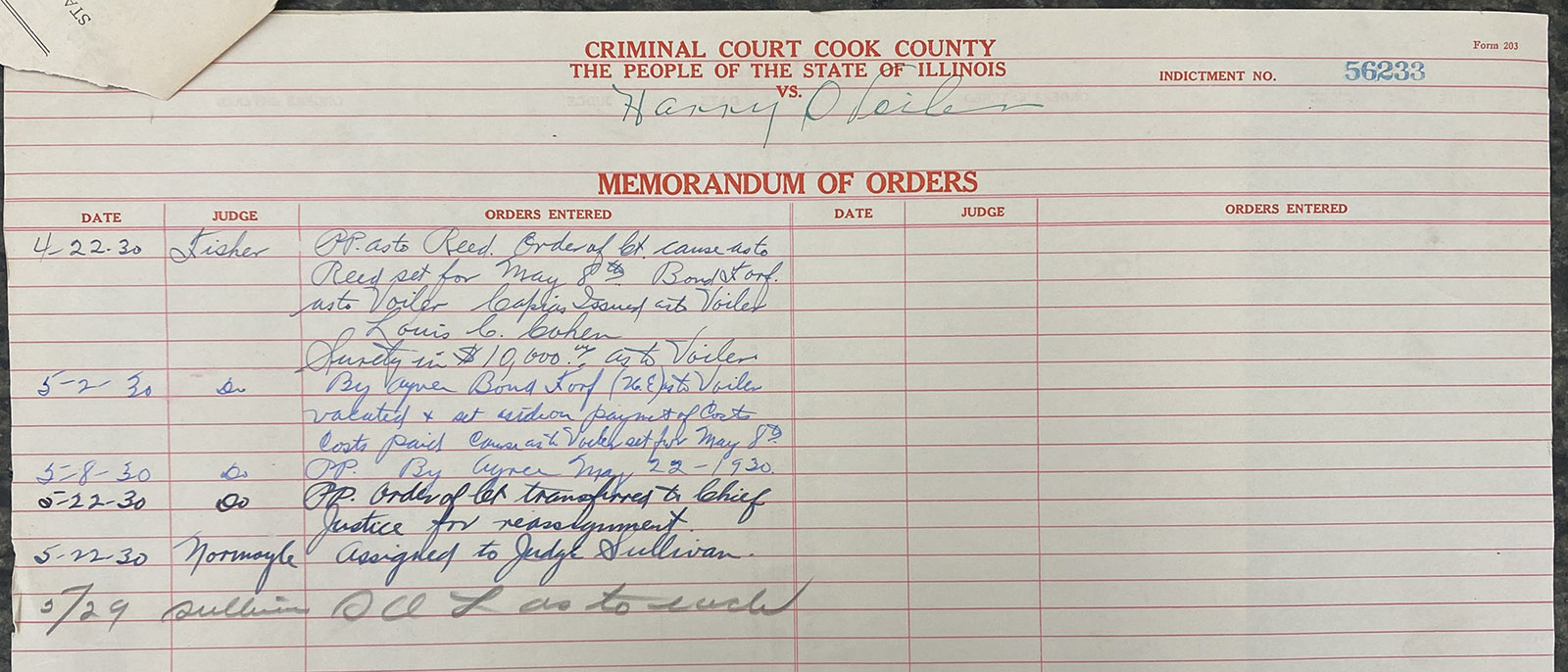

A grand jury indicted Voiler and Reed on charges of assault with intent to murder.127 They were released from jail when a hotel owner named Louis C. Cohen put up his $250,000 property—the northeast corner of La Salle and Division Streets—as a surety, guaranteeing that Voiler and Reed would return to court for their trial.128 But there never was any trial.

The court issued four subpoenas for Leon Sweitzer to appear in court. As the shooting victim, he would be the most important witness who could testify about what happened. He’d testified before the grand jury. But now, sheriff’s deputies seemed unable to find him.

They went to his home address—5428 Jackson Boulevard—but reported that he’d moved. The court then sent a deputy to a police station, with another subpoena for Sweitzer. Had Sweitzer been in custody there? If so, he wasn’t there anymore. Another subpoena sent a deputy to a different address: 723 North Menard Avenue. When the deputy came back, he’d jotted down a note saying, “Mail Box,” possibly indicating that he’d left a message for Sweitzer.129

Judge Harry M. Fisher was overseeing the case, but on May 22—for unknown reasons—it was transferred to the chief justice for reassignment. The new judge who was assigned to the case, Sullivan, quickly dismissed it on May 29. The court documents don’t include any explanation for why the case fizzled out—just a brief notation: “SOL as to such.”130 That’s court jargon for “stricken on leave to reinstate,” meaning that the charges were thrown out.131

Did Sweitzer decide, for some reason, that he didn’t want to testify against Voiler and Reed? Did someone at the courthouse decide to let the case die? The reasons why the prosecution fell apart may never be known. But like so many of Chicago’s criminal cases during the Prohibition Era, the Green Mill shooting case went nowhere.

Postscripts

In spite of the police order shutting it down, Leon Sweitzer’s Little Club reopened—only to be closed again in October 1930, when a federal judge issued a permanent junction padlocking the joint. The Chicago Daily News described it as the “scene of shootings, stabbings, attempted bombings and considerable whoopee.”132 Five years after he’d been fired by the Chicago police, Sweitzer was reinstated as a patrol officer in 1934.133 When he died in 1961, he was remembered as “one of the most colorful detectives to serve on the homicide detail.”134

Harry Voiler made news again in 1933, when California authorities charged him with stealing jewelry and cash from another famous female entertainer, Mae West. But that case seemed to fizzle out, too, when Illinois officials refused to extradite Voiler, because he said he was suffering from tuberculosis.135 Voiler later became the publisher of The Morning Mail in Miami, where he was allegedly involved in mob-connected bookmaking.136 In 1953, the U.S. government tried to deport Voiler to Romania, the homeland he’d departed when he was only three months old,137 but a judge overturned the decision to exile him.138

And what was the true identity of Sam Cimman, the man who told author Louise Berliner that he’d been one of the Green Mill’s co-owners? “I continue to be so baffled about all this,” Berliner said, after I told her about my difficulties finding information on Cimman. “I was so young when I interviewed this guy, and I took him at his word that he was who he said he was.”139

We may never know who Cimman really was, but it’s interesting to note that he used 127 North Dearborn Street as his address when he contacted Berliner in 1981.140 It may merely be a coincidence, but that same skyscraper—the Unity Building—was also the headquarters of Bugs Moran’s North Side mob when it was controlling the Green Mill in the 1920s. For a century, the building was a hub for politicians and politically connected Chicagoans. “The stories the Unity Building, across the street from the Daley Center, could tell would be of backroom politics, of the ward heelers, courtroom weasels and bit players trudging through its musty hallways,” Tribune reporter John Kass wrote in 1989, shortly before the building was demolished.141

We may never know who Cimman really was, but it’s interesting to note that he used 127 North Dearborn Street as his address when he contacted Berliner in 1981.140 It may merely be a coincidence, but that same skyscraper—the Unity Building—was also the headquarters of Bugs Moran’s North Side mob when it was controlling the Green Mill in the 1920s. For a century, the building was a hub for politicians and politically connected Chicagoans. “The stories the Unity Building, across the street from the Daley Center, could tell would be of backroom politics, of the ward heelers, courtroom weasels and bit players trudging through its musty hallways,” Tribune reporter John Kass wrote in 1989, shortly before the building was demolished.141

Louise Berliner’s book, Texas Guinan: Queen of the Nightclubs, was reissued in 2023.

Texas Guinan returned to Chicago in 1931, performing at the Planet Mars, a nightclub on Randolph Street near Wells Street (with Voiler acting as her manager once again).142 When the feds raided the joint on December 31, 1931, they even hauled out the furniture. “This is terrible,” Guinan remarked. “I’ve got $10,000 worth of reservations for New Year’s Eve. … Well, we’ll make whoopee here tonight if we all have to sit on the floor.”143 Guinan was disappointed when authorities decided not to prosecute her, depriving her of another chance to put on a big show in a courtroom.144

Guinan was back in Chicago for the world’s fair in 1933, performing that July in a venue called the Pirate Ship at the Century of Progress exposition.145 Officials suspected that she contracted amoebic dysentery during an outbreak that summer at the Congress Hotel. Months later, after she collapsed from an intestinal illness in Vancouver, British Columbia, she was taken to a hospital for surgery and died on November 5, 1933. She was 49 years old.146

“She gave a lot of spice to those wonderful days of prohibition,” Doherty wrote. “A lot of folk are never going to forget her.”147

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

Also see the Addendum: 1930 Photos of Lawrence Avenue in Uptown

Footnotes

1 James Doherty, “Texas Guinan, Queen of Whoopee!” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 4, 1951, Grafic Magazine, 4–5.

2 Louise Berliner, Texas Guinan: Queen of the Nightclubs (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993), xi. Cited source: Dallas Morning News, November 6, 1933.

3 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 11.

4 Berliner, Texas Guinan (paperback, 2023), 44–46.

5 Texas Guinan, “Nightlight Saving,” Chicagoan, March 1, 1930, 15. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v008-i12/mvol-0010-v008-i12.xml#page/17/mode/1up.

6 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 3.

7 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 98–99.

8 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 150.

9 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 98–99.

10 Berliner, Texas Guinan, xi.

11 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 131.

12 “Guinan and Bordoni Arrive Next Week,” (Chicago) Daily Times, October 19, 1929, 23; Amy Leslie, “Irene Bordoni Brings ‘Paris’ for Long Run,” Chicago Daily News, October 21, 1929, 13.

13 Amy Leslie, “Stars Entertain in the Gardens and Night Clubs,” Chicago Daily News, November 1, 1929, 17.

14 “Tex Guinan Gives Drys Big Hand in Night Club Raid,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 12, 1929, 5.

15 Guy Murchie Jr., “Capone’s Decade of Death,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 9, 1936, part 7, 1.

16 “U.S. Dry Writs Issued Against 3 Night Clubs,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 1, 1929, 16.

17 “Tex Guinan Gives Drys Big Hand in Night Club Raid.”

18 “U.S. Dry Writs Issued Against 3 Night Clubs.”

19 “Come On Suckers! Guinan Buys Club,” (Chicago) Daily Times, December 12, 1929, 43.

20 “Guinan’s Club Finish in Chi. Real Blow-Off,” Variety, March 26, 1930, 74, https://archive.org/details/variety98-1930-03/page/n293/mode/2up.

21 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 161–162.

22 “Court Orders Formal Charge in Cafe Shooting,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 25, 1930.

23 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 161–162.

24 Doherty, “Texas Guinan.”

25 Laurence Bergreen, Capone: The Man and the Era (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 336–339; Jonathan Eig, Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America’s Most Wanted Gangster (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 226–233.

26 Anonymous (Hal Andrews), Chicago Gang Wars in Pictures: X Marks the Spot (Rockford, IL: Spot Publishing, 1930), https://archive.org/details/chicagogangwarsi00rock, 56.

27 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 162.

28 Doherty, “Texas Guinan.”

29 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 30, 1929, 31; “Current Entertainment,” Chicagoan, February 15, 1930, 4. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v008-i11/mvol-0010-v008-i11.xml#page/4/mode/1up.

30 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 162.

31 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, December 17, 1929, 48.

32 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 162–163.

33 Advertisement, (Chicago) Daily Times, December 16, 1929, 73.

34 “Drift-Bound City Digs Out,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 20, 1929, 1.

35 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 163.

36 “With the Cabarets,” (Chicago) Daily Times, Dec. 21, 1929, 22.

37 Doherty, “Texas Guinan.”

38 Advertisement, (Chicago) Daily Times, January 4, 1930, 21.

39 “With the Cabarets,” (Chicago) Daily Times, January 4, 1930, 23.

40 “With the Cabarets,” (Chicago) Daily Times, January 25, 1930, 44.

41 W. Boyd Gatewood, “Pastor’s Son Gone Wrong, Says Hot Check Roisterer,” (Chicago) Daily Times, February 5, 1930, 3.

42 Lucia Lewis, “La Guinan: A National Weakness,” Chicagoan, February 15, 1930, 28–30. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v008-i11/mvol-0010-v008-i11.xml#page/30/mode/1up.

43 Texas Guinan, “Nightlight Saving,” Chicagoan, March 1, 1930, 15. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v008-i12/mvol-0010-v008-i12.xml#page/17/mode/1up

44 “Fourth Victim in Four Days Shot in Auto,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 3, 1930; Homicide in Chicago, 1870-1930, https://homicide.northwestern.edu/database/9372/.

45 Chicago Gang Wars in Pictures, 56.

46 Arthur Sheekman, “Ahead of the Times,” (Chicago) Daily Times, March 3, 1930, 14.

47 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 163.

48 John Boettinger, “Murder, Arson, Robbery—Life of Leo V. Brothers,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 26, 1931, 6.

49 John Boettinger, “Story of Clews Leading to the Lingle Slayer,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 22, 1931, 6.

50 Trial transcript, 690–691, People of the State of Illinois, Defendant in Error, v. Leo V. Brothers, Illinois Supreme Court, case 20981, October term, 1931, vault 45942, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

51 Boettinger, “Story of Clews…”

52 Louise Leung, “Brothers a Sober, Home-Loving Boy, Says Entertainer,” (Chicago) Daily Times, February 7, 1931, 4.

53 “Vincent Langford ‘Leo’ Brothers,” Find a Grave, accessed August 13, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5337730/vincent-langford-brothers. Cited sources include death certificate.

54 “Labor Organizer Sought as Slayer of Service Driver,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 4, 1929, 3; “Bombing Chauffeur Charged With Arson,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 21, 1929, 17.

55 Richard Babcock, “Prince of the City,” Chicago magazine, November 2009, https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/november-2009/prince-of-the-city-the-mysterious-mob-hit-on-1920s-tribune-reporter-jake-lingle/.

56 Boettinger, “Story of Clews…”

57 John Boettinger, “Lingle Killer’s Crime History Is Told in Full,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 25, 1931, 6.

58 Boettinger, “Murder, Arson, Robbery.”

59 Trial transcript, 690–691, People v. Leo V. Brothers.

60 Boettinger, “Lingle Killer’s Crime History Is Told in Full.”

61 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 163.

62 Boettinger, “Murder, Arson, Robbery.”

63 “Guinan’s Club Finish in Chi. Real Blow-Off,” Variety, March 26, 1930, 74, https://archive.org/details/variety98-1930-03/page/n293/mode/2up; “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe; 2 Held,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1930.

64 “Texas Guinan May Testify for Brothers,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, Jan. 23, 1931, 1.

65 W.A.S. Douglas, “On the Sun Beam,” Chicago Sun, December 28, 1942, 24.

66 “Police Seize Merrymakers in Wild Chase,” Chicago Daily News, March 10, 1930, 3; Boettinger, “Murder, Arson, Robbery.”

67 “Two More Rich Young Idlers,” Daily Worker, August 11, 1924, 3.

68 “Police Tree Rich Boys in Wild Chase,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 4, 1924, 1.

69 “3 Joy Riders Captured in Chase Face Court Today,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 11, 1930, 10.

70 Boettinger, “Murder, Arson, Robbery.”

71 Lewis, “La Guinan.”

72 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, March 24, 1930, 1.

73 “Shooting in Guinan Club,” (New York) Daily News, Brooklyn Edition, March 24, 1930, 2, 9.

74 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe; 2 Held,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1930.

75 “Guinan’s Club Finish in Chi. Real Blow-Off,” Variety, March 26, 1930, 74, https://archive.org/details/variety98-1930-03/page/n293/mode/2up.

76 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 164–165. Cited source: Letter from Michael Guinan to Pearl Guinan Smith, March 13, 1930, Pearl Guinan Smith family papers.

77 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 163.

78 Doherty, “Texas Guinan.”

79 Rose Keefe, The Man Who Got Away: The Bugs Moran Story: A Biography (Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2005), 250; “Moran Aid Shot in Rum Feud,” (Chicago) Daily Times, December 2, 1929, 2; “Bootleg Circles Skeptical About Albin as Gunman,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 3, 1929, 17.

80 Doherty, “Texas Guinan.”

81 “Billiken,” Wikipedia, accessed August 14, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billiken.

82 “Kill Gangster: Body in River,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 17, 1930, 1; “Call Slain Gangster Alky Doublecrosser,” (Chicago) Daily Times, March 17, 1930, 2.

83 “Hunt Pal of Murdered Gunman,” (Chicago) Daily Times, March 17, 1930, 2; “Gunmen Kill Foe and Toss Body From Car,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 18, 1930, 1.

84 INS, “Gang Warfare Reaching Critical State,” Clinton (IL) Daily Journal and Public, June 5, 1930, 1.

85 “20th Ward Gangster Slain,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 4, 1930, 1–2; International News Service, “Gang Warfare Reaching Critical State,” Clinton (IL) Daily Journal and Public, June 5, 1930, 1.

86 “Capone Calls Gang to Meet Him in Indiana,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 19, 1930, 1, 8.

87 Bergreen, Capone, 353; “Al Capone,” FBI, accessed August 3, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/al-capone.

88 “Al Capone’s Own ‘Racket’ Story,” Chicago Evening American, March 22, 1930, 1, 2.

89 “Little Club Must Close,” Chicago Evening American, March 24, 1930, 2.

90 “Shooting in Guinan Club,” (New York) Daily News, Brooklyn Edition, March 24, 1930, 2, 9.

91 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe; 2 Held,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1930.

92 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, March 24, 1930, 1.

93 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

94 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting.”

95 “Court Orders Formal Charge in Cafe Shooting,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 25, 1930.

96 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe; 2 Held,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1930.

97 “Guinan’s Club Finish in Chi. Real Blow-Off,” Variety, March 26, 1930, 74, https://archive.org/details/variety98-1930-03/page/n293/mode/2up.

98 “Charges Shots at Guinan Club to ‘Hood’ Rule,” Chicago Daily News, March 24, 1930, 1, 3.

99 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

100 “Guinan’s Club Finish in Chi. Real Blow-Off.”

101 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting.”

102 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

103 “Shooting in Guinan Club.”

104 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

105 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting.”

106 “1,000 in Panic at Green Mill Cafe Shooting,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 23, 1930.

107 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

108 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting.”

109 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting”; “1,000 in Panic at Green Mill Cafe Shooting.”

110 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

111 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting.”

112 “Tex’ Grief Piles Up; Voiler Wanted in Ohio for Robbery,” (Chicago) Daily Times, March 25, 1930, 36.

113 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting.”

114 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

115 “Hold 2 in Guinan Cafe Shooting.”

116 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

117 Tom Killian, “‘Hooey,’ Says Tex,” (Chicago) Daily Times, March 24, 1930, 15.

118 “Charges Shots at Guinan Club to ‘Hood’ Rule,” Chicago Daily News, March 24, 1930, 1, 3.

119 “Gunplay Brings Padlock to Tex Guinan’s Cafe,” Belvidere (IL) Daily Republican, March 23, 1930, 1.

120 “Gunplay Shuts Tex Guinan’s Cafe.”

121 Killian, “‘Hooey,’ Says Tex.”

122 “Little Club Must Close.”

123 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 165. Cited source: New York American, March 31, 1930.

124 Irene Kuhn, “‘Pleasure Club’ Closes its Court Run Today,” (New York) Daily News, April 2, 1930, 9.

125 “Editorially,” Chicagoan, April 12, 1930, 7. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v009-i02/mvol-0010-v009-i02.xml#page/9/mode/1up.

126 “Court Orders Formal Charge in Cafe Shooting,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 25, 1930.

127 Indictment, March 27, 1930, State of Illinois v. Arthur Reed and Harry O. Voiler, Criminal Case 56233, 1930, Clerk of the Cook County Circuit Court Archives.

128 Recognizance and real estate schedule for Harry O. Voiler, May 2, 1930; Recognizance and real estate schedule for Arthur Reed, March 31, 1930, Illinois v. Reed and Voiler.

129 Subpoenas, Illinois v. Reed and Voiler.

130 Memorandum of orders, Illinois v. Reed and Voiler.

131 “Expungement and Sealing,” James G. Dimeas & Associates, accessed August 12, 2024, https://www.chicagoareacriminallawyers.com/practice-areas/expungement-and-sealing/.

132 “Little Club, Scene of Rows, Whoopee, Closed,” Chicago Daily News, October 4, 1930, 1.

133 “Sweitzer Cousin Faces Citation in Alimony Case,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 5, 1936.

134 “Funeral Rites Saturday for Leon Sweitzer,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 20, 1961, Sports-Business, 11.

135 United Press, “L.A. Gang Suspect Wise-Cracks Self Into Prison Again,” Hanford (CA) Sentinel, September 29, 1933, 1; “Voiler Freed as Mae West Case Is Up 15th Time,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 9, 1934, 14.

136 Bert Collier, “S & G Data Barred at Voiler Deportation Hearing,” Miami Herald, June 11, 1953, 23.

137 David Kraslow, “Voiler Is Ordered Deported From U.S.,” Miami Herald, June 27, 1953, 9.

138 David Kraslow, “Judge Frees Voiler,” Miami Herald, Sept. 25, 1953, 5.

139 Louise Berliner, email to author, August 8, 2024.

140 Louise Berliner, email to author, February 23, 2023.

141 “Unity Building (Chicago),” Wikipedia, accessed February 1, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unity_Building_(Chicago); John Kass, “Historic Building Is Out of Time,” Chicago Tribune, September 4, 1989, 8.

142 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 175.

143 “Dry Agents Strip Texas Guinan’s Club,” Urbana Daily Courier, December 31, 1931, 1. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=TUC19311231.2.4&srpos=3&e=——193-en-20–1-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill%22———.

144 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 176.

145 Berliner, Texas Guinan, 185.

146 “Texas Guinan,” Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Texas_Guinan; Associated Press, “Guinan Death Linked With Chicago Epidemic,” Baltimore Sun, November 11, 1933, 7; “15 Dead Men,” Mid-West Progressive, November 16, 1933, 5.

147 Doherty, “Texas Guinan.”