CHAPTER 40 of THE COOLEST SPOT IN CHICAGO:

A HISTORY OF GREEN MILL GARDENS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF UPTOWN

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

Greeted by a cheering crowd, William Hale Thompson partied at Rainbo Gardens on April 5, 1927, the day he won Chicago’s election for mayor.1 Rainbo was one of Big Bill’s favorite places to hang out. It was where he’d announced his comeback candidacy.2 And he went back on the night after his election victory, when 3,000 people gathered at Rainbo for a “jollification” to celebrate Thompson’s imminent return to office.

“We’ll do away with the bread line,” Thompson told the crowd. “We’ll put the police back on their beats and drive the crooks out of Chicago and we’ll make Chicago the greatest city in the world.”3

In fact, many people saw Thompson’s win as a signal that Chicago would once again be a “wide open” city, regardless of whether the U.S. Constitution said it was a crime to serve alcohol. With Thompson reclaiming the mayor’s office, people expected the booze to flow more freely in Chicago. But the feds had other ideas. A year later, they would padlock Rainbo Gardens, closing it for violating prohibition laws. And before long, Rainbo owner Fred Mann’s life would come to a tragic end.

While the Green Mill went through ups and downs in the mid-1920s—changing owners, closing down, reopening as the Montmartre Cafe, getting shut down by a federal judge, and reopening as the New Green Mill—the party never seemed to end at Rainbo Gardens, located half a mile to the west, on Clark Street just north of Lawrence Avenue. Decades earlier, that spot had been a roadhouse tavern serving the German Americans who visited St. Boniface Catholic Cemetery across the street.

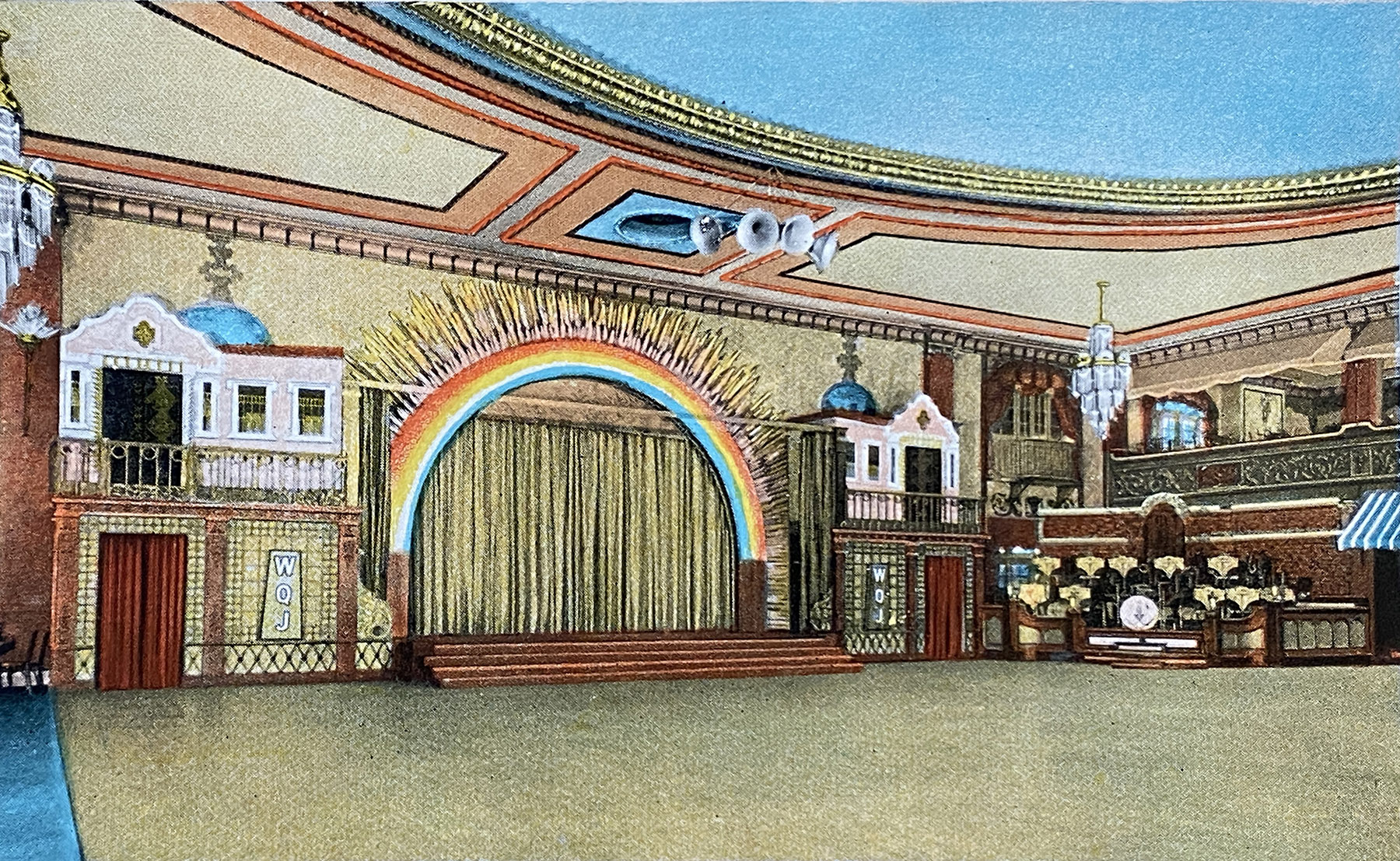

The ballroom and stage of Mann’s Million Dollar Rainbo Room, circa 1927. Postcard A113903. Curt Teich Postcard Archives Collection, Newberry Library.

By 1927, Rainbo may well have been the North Side’s most popular night spot. With a café seating 2,000 and dancing accommodations for 1,500, it was “probably the largest cafe in America conducted strictly on a dine and dance basis,” reported Variety, the national entertainment newspaper.4

Mann boasted that he’d spent a million dollars expanding and renovating Rainbo Gardens, and advertisements touted the luxurious venue as Mann’s Million-Dollar Rainbo Room.5 The Chicagoan magazine called it the “Million Dollar play place”6 and a “showy place with outdoor show, noisy dancing, reasonable latitude in all proper directions and an extensive billing. Food, too.”7

The Tribune called it a “famous palace of night life and merriment,” describing it as “one of the city’s show places where well known people are frequently seen.” For a time, Rainbo included “an elaborately appointed gambling parlor that was certainly no place for a piker,” the newspaper added.8

The Daily News called it a “miniature Monte Carlo.”9 Chicago mobster James V. Mondi (who worked at various times for Mont Tennes, Al Capone, and Jake Guzik) reputedly furnished protection for Rainbo Gardens’ gambling operation. One writer described it as “the highest powered joint on the north side with 6 roulette wheels, 2 ‘bird cage’ and blackjack.”10 Mann eventually shut down the roulette wheels when he became “astounded that citizens looked with disfavor on his operation of a gambling room in the Rainbo gardens,” the Daily News recounted, with a touch of sarcasm.11

Mayor Thompson, who was described as Mann’s close friend and “bosom companion,” was frequently seen at Rainbo.12 He often gave short speeches during the testimonial banquets that Rainbo hosted. These dinners became a ritual of Chicago politics around 1927—or a “racket,” according to the Tribune. A few thousand people paid $5 each to attend a dinner honoring one of Chicago’s government bosses or elected officials, ranging from the health commissioner and the city attorney to various aldermen.

The dining area in Mann’s Million Dollar Rainbo Room, circa 1927. Postcard A113901. Curt Teich Postcard Archives Collection, Newberry Library.

At each banquet, people gave speeches praising the guest of honor. “He is lauded as a hale fellow well met, a prince to his friends, kind to dumb animals, a masterful leader, and, always, a man of the people, heaven-sent to fill the job to which he was appointed,” the Tribune wrote. “The speakers, mostly ‘lifelong friends,’ relate his struggles up from messenger boy to friendship with Mayor Thompson.”

A shiny new automobile, worth around $5,000, was usually sitting in a corner of the banquet hall. Purchased with some of the money from those $5 tickets, the car was given to the guest of honor as a “token of regard.” When Thompson himself was honored during a testimonial banquet at Rainbo Gardens, the attendees pooled their money together to give him a Lincoln Sport Touring car—just to show him what a great mayor he was.

At least 30 such banquets were held at Rainbo and a few other venues during the 10 months after Thompson won the election. “It wasn’t so bad at first, but now it’s a big pain,” an alderman grumbled (anonymously) to the Tribune, as he wrote a check for a dozen tickets to a banquet. “Same old noise—you lay out $100 for tickets. If you go, you are bored to death by dumb speeches you know by heart. To stay awake you have to get soused, and then you stay home from the office the next day. If you don’t go, you’re a bum and a cheap skate.”

Some people questioned whether money was being diverted from all of those ticket sales. The organizers insisted they were using every penny to put on the event and present an automobile or another gift to the honoree. But critics wondered if someone was pocketing some of the money.13 A group of Rainbo Gardens shareholders insisted that the opposite was happening: They accused Fred Mann of using the company’s money and property to subsidize these banquets, running the events at a loss. Why would he do that? The shareholders said it was Mann’s way of securing “influence and safety from prosecution for violating the law.”14

Rainbo was one of Chicago’s most prominent gambling spots in 1927, a year of topsy-turvy changes in the city’s gambling scene. Following Thompson’s election as mayor, “gambling joints, beer and moonshine parlors and disorderly houses … sprang up like mushrooms,” the Daily News reported. As the year went on, authorities sometimes cracked down on gambling—only to allow the games to begin again, a short time later. Chicago’s various mob factions and a “syndicate” of powerful politicians vied for control over the games. At times, the newspapers reported that gambling was rampant everywhere. At other times, they said the games were all shut down.

In late July, the Daily News sent a reporter to see what sort of gambling was taking place at Rainbo Garden. Near the building’s entrance on Clark Street, the reporter found a door leading up to the second-floor roulette room. The door was guarded by “a slick-haired youth in white flannel and a blue serge coat.” The reporter asked the young man if the wheels were running. The guard asked to see his card, asking: Who do you know? Do you know the judge?

The guard left for a minute and came back with the house manager, “Baby Face” or “Doll Face” Schreiber, who was similarly attired in spotless white flannels and a blue serge coat. “All right, come on up,” Schreiber told the reporter.

But as the reporter and Schreiber went up the stairs, they ran into Al Mann, the son of Rainbo owner Fred Mann. Al excitedly called Schreiber aside, whispering, “You’ve let a newspaperman in; you can’t let him go up.” But it was too late. The reporter had already entered the gambling parlor, where he shook the hands of several prominent politicians he saw in the room.

“A visitor, sinking intro three inches of heavy carpet, notes that many mirrors, much highly polished mahogany and brass, and an ornamental lighting system have been used in developing a tone of luxury,” the reporter noted. “… the roulette room is as nifty a ‘Monte Carlo’ as Chicago has to offer. A hundred men and women, most of them in evening dress, piling stacks of chips on the numbers and colors on the little ball went swishing around to a lucky result for either the players or house, lent an atmosphere of intense excitement.”

In earlier days, Rainbo had only one roulette layout, which was hidden away in a well-protected spot. But now, “six highly polished wheels and two blackback and chuck-a-luck games were going full blast.”15

There were reports that summer of “wide and vigorous public protest against such public gambling as has been conducted at the Rainbo.”16 In late November, as authorities shut down most gambling in the city—ostensibly so that Chicagoans would have enough money to spend on their Christmas shopping—Rainbo Gardens was one of the few places that stayed open. Its roulette room was jammed full of people, including many folks who might have gone elsewhere if those other gambling parlors had been open.

“Al Mann was kept busy denying the six wheels were equipped with electric stop and go devices controlled by the house’s operator,” a Daily News reporter observed. “Three blackjack stands and two gold bird cages received steady play. At least a third of the players were women.”

“Baby Face” Schreiber, the house manager, smiled as he expressed regret for the other gambling houses that weren’t allowed to stay open. “But it won’t be for long,” he remarked. “There’s too much money in the gambling racket. They might have meant well when they told gambling joints to shut up to give the merchants a chance, but I’ll bet a hat they’ll give the boys an opportunity to make some Christmas money for themselves before Santa Claus gets here.”17

A few days before Christmas, the city’s clampdown on gambling finally seemed to have an effect on this North Side hot spot. “The Rainbo, … usually the brightest spot in the whole town from a gambler’s viewpoint, was found to be running ‘under wraps’ with only a favored few of its former large clientele being given a chance at roulette,” the Daily News reported.18

At the same time, a major addition to the Rainbo complex was unveiled, with Mayor Thompson presiding over the grand opening on December 21, 1927.19 Fred Mann had spent $300,000 building a sports arena on a portion of Rainbo’s outdoor grounds. Following the closing of Green Mill Gardens’ outdoor area a few years earlier, this was another sign that Chicago’s era of big amusement gardens was coming to an end.

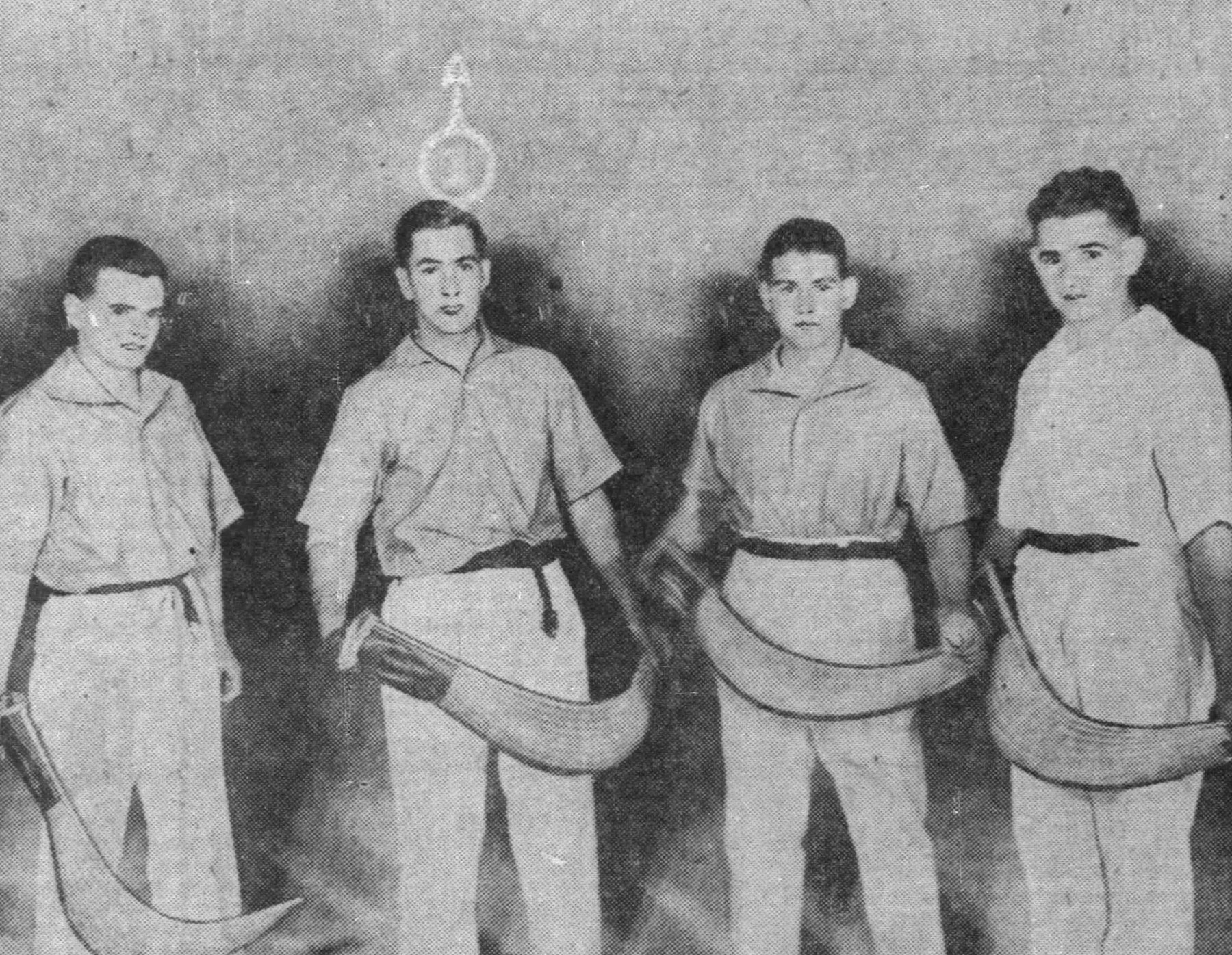

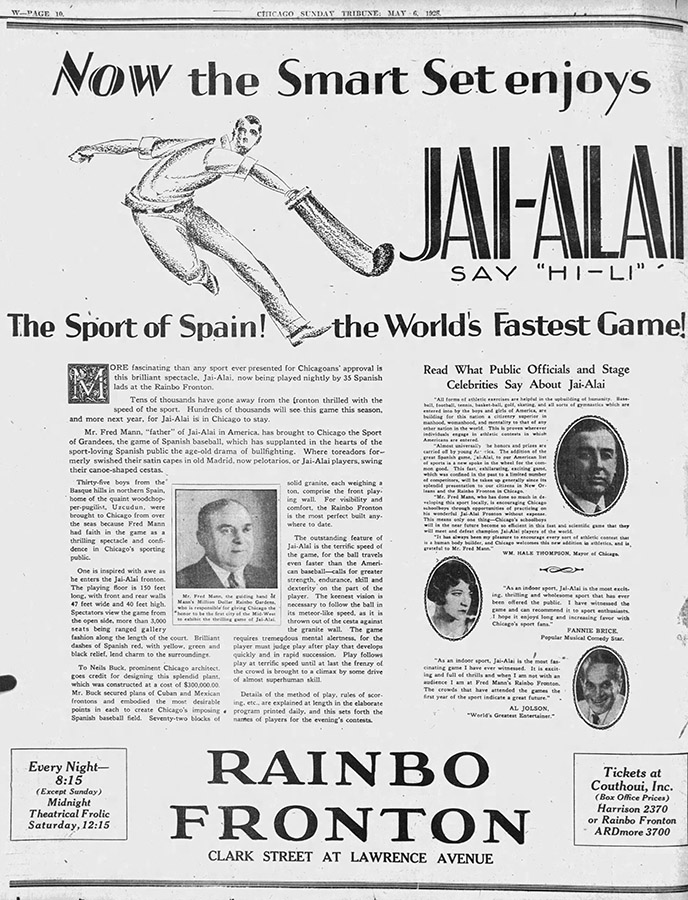

With as many as 3,000 seats, the new building was a fronton, designed to host games of jai alai, a Spanish game whose players strap long hand-shaped baskets to their wrists, propelling a ball against a wall. “Play follows play at terrific speed until at last the frenzy of the crowd is brought to a climax by some drive of almost superhuman skill,” an ad for the Rainbo Fronton promised.

Mann brought in 35 young men from Spain’s Basque region20 to play in the fronton, which was operated by a newly formed corporation, the Rainbo Exhibition Company.21 But a Tribune reporter writing under the byline “Mexican Joe” observed: “The spectators weren’t one-tenth as enthusiastic as are the spectators in Mexico City or Havana.”22 The enthusiasm may have increased as the Rainbo came up with a legal loophole allowing a form of betting—spectators could contribute money to a fund for the athletes, receiving a dividend if their selected player won.23

“It is a strange place for a jazz-floor and a hall of games,” Charles Collins wrote in February 1928 for the Chicagoan magazine. “Across the street is the cemetery of St. Boniface. On the right flank and the left are the exhibition yards of tombstone carvers. But the Rainbo Gardens rejoice in this ironic contrast. The environment expresses the hedonist’s philosophy: ‘Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow—.’ Somnolent Ravenswood is behind; frivolous Uptown, before. It is a region of the quick and the dead.”24

When Al Jolson came to Chicago in the spring of 1928 and spent a few weeks starring in a show at the Four Cohans theater25 (a.k.a. the Grand Opera House),26 he made an appearance at the Rainbo Fronton.27 “As an indoor sport, Jai-Alai is the most fascinating game I have ever witnessed,” Jolson said, according to a Rainbo advertisement. “It is exciting and full of thrills and when I am not with an audience I am at Fred Mann’s Rainbo Fronton. The crowds that have attended the games the first year of the sport indicate a great future.”28

This was just a few months after Jolson’s movie The Jazz Singer had astonished Chicago audiences with its synchronized music when it opened at the Garrick Theatre on November 29, 1927.29 (Jolson is sometimes mentioned as an entertainer who performed at the Green Mill, but I haven’t found any evidence that he did.)

While Rainbo Fronton tried to build a Chicago audience for jai alai games, the adjacent Rainbo Gardens came under attack from prohibition agents. An earlier case cleared the way for the feds to shut down the Rainbo. A U.S. appellate court had ruled in March 1927 against three nightclubs on South Wabash Avenue—Al Tearney’s Town Club, Friars Inn, and Moulin Rouge—whose owners insisted they weren’t breaking any laws when they let customers bring in their own alcohol. Judge Albert B. Anderson disagreed. As he pointed out, the Volstead Act said a place was a nuisance if intoxicating liquor was “kept” there. And the way Anderson read the law, liquor was being “kept” at a business if customers were carrying their own booze inside.

Judge George T. Page concurred, but a third judge on the panel, Samuel Alschuler, dissented. “Can the liquor be said to be ‘kept’ on the premises for ‘commercial purpose’ if … it is not ‘kept’ there at all?” Alschuler asked. He said it wasn’t fair for a judge to issue an order—without any input from a jury—imposing the “drastic penalty” of shutting down a business for a year, simply based on this questionable interpretation of the law.30

“It is a most unjust decision,” Jack Denham, assistant manager of the Blackstone Hotel, remarked. “We do everything in our power to eliminate the hip flask. But, according to this ruling, if a man simply walks in with a flask and draws the cork, we can be held legally responsible.”

Fred Mann was also dismayed. He said would be impossible for places like the Rainbo to prevent customers from bringing in their own liquor. “Two watchers at the door permit no suitcases or suspicious bundles to be brought in,” he said. “But if a man gets by with a bottle and somebody smells it, how on earth are we going to help it?”31

On October 17, 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal in the case, allowing Anderson’s ruling to stand.32 The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, based in Evanston, cheered. “The Supreme Court refutes all the wet arguments when it refuses to permit drinking from flasks in public,” said Ella A. Boole, the group’s national president. “… We hope that merchants will take cognizance of the decision and cease selling hip flasks. In Chicago and even in Evanston samples of them are still displayed in windows in open defiance of the spirit of the prohibition law.”

One cabaret owner expressed befuddlement at the situation. “We don’t know what to do,” he said. “We can’t insult our patrons by searching them before we serve them soft drinks. We are damned if we do and damned if we don’t.”33

The Supreme Court’s action gave a green light for the feds to shut down cafés and cabarets by using “observation evidence.” This meant that the prosecutors didn’t need to seize beverages and get scientific evidence that these drinks contained alcohol. As long as federal agents saw people drinking beverages that obviously looked and smelled like alcohol, that was sufficient reason for a judge to issue a permanent injunction shutting down the place for a year.34

Between November 1927 and February 1928, agents made seven undercover visits to Rainbo Gardens. Each time, they saw customers order ginger ale and ice and then mix in alcohol from bottles under their tables. “These persons were sober before they began the drinking of said liquor but after taking two or three drinks thereof they became boisterous and noisy, and it was perfectly apparent … that they were in a state of intoxication,” agent Frederick D. Silloway said in an affidavit.35

“While the show was in progress a woman on the south side of the room, who appeared to be a high state of intoxication, became noisy and boisterous,” agent George A.E. Williams said.36

“Waiters passed about among the crowd from time to time with the drinking of liquor proceeding in their presence,” agent Louis F. Cole said, “but … no effort was made by any of the waiters to stop the patrons from the drinking of liquor.”37

“About 11 o’clock about eight hundred people were seated in the room,” agent John L. Smysor said. “… The use of liquor appeared to be general throughout the room at the various tables; … such drinking was done openly, in the presence of the waiters; … waiters made no objection thereto.”38

The agents “saw many intoxicated persons upon said premises behaving in a boisterous and disgusting manner and saw mere boys and girls, 16 to 18 years of age, in such a high state of intoxication that they had be assisted from the room,” U.S. attorney George E.Q. Johnson said.39

On the evening of Saturday, February 4, 1928, federal agents slipped into a dozen of Chicago’s most prominent nightclubs, including Rainbo Gardens. These advance scouts confirmed that alcohol was on the premises, setting the stage for early-morning raids. At 1:30 a.m., 150 agents split up into squads, departing the Transportation Building40 at 600 South Dearborn Street in the Printers Row district41 and simultaneously raiding 12 cabarets across the city.

Variety reported that the agents didn’t have search warrants, apparently believing that warrants weren’t necessary. At the notorious Midnight Frolics, they found no alcohol.42 But at Rainbo Gardens, the agents seized 16 bottles and two metal flasks, “several of which contained whisky and gin,” authorities said.43 When agents arrived at the Rendezvous at Diversey Boulevard and Clark Street—where entertainer Joe Lewis was making his comeback, after suffering a brutal attack that nearly ended his life—many of the 500 patrons tried to rush out through the doors. The feds collected 50 bottles, more than they found anywhere else that night. (The Green Mill escaped scrutiny during these raids, perhaps because it may have not have been open for business at the time.)

Although the recent appellate court decision meant that the feds didn’t necessarily need any bottles of alcohol to make their case, they gathered this sort of evidence anyway. The regional prohibition administrator said his agents weren’t arresting anyone on criminal charges. Instead, they were focused on getting court injunctions to shut down Chicago cabarets where people drank alcohol.44

According to the Daily News, the cabaret owners were both “angry and philosophic,” as they “declared that they had been doing their best to co-operate with the prohibition enforcement agencies and had done everything but search their patrons for concealed liquor.”45 The owners reportedly united to put up a legal fight against the crackdown, with Fred Mann leading the charge.46 Mann, however, downplayed the idea that he was waging a legal fight on behalf of the other cabaret owners. “I’ll retain an attorney and fight my own battle,” he said. “It’s a case of every man for himself now.”47

Rainbo Gardens’ attorney, Benedict J. Short, said the government’s allegations were “so indefinite, vague and uncertain” that the defendants couldn’t comprehend exactly what they were being accused of. He said the feds had no right to conduct a raid without a search warrant. And Short repeated the same argument that the lawyers for Al Tearney’s Town Club, Friars Inn, and Moulin Rouge had made earlier: He said it wasn’t illegal for a place like Rainbo to let customers drink their own alcohol. Unfortunately for Short, the Supreme Court had already refused to consider this argument.48

Mayor Thompson traveled to Washington, D.C., where he pleaded with federal officials to take it easy on Rainbo Gardens and other Chicago cafes and cabarets. Thompson had lunch at the White House on February 24.49 (It’s unclear whether the president, Calvin Coolidge, took part in this lunch.) Meeting on the following day with Andrew W. Mellon, the treasury secretary, Thompson complained that the prohibition crackdown seemed to be targeting his friends. As he came out of the meeting, Thompson told reporters, “I understand they are getting ready to use the prohibition forces for political purposes against Thompson fellows.”

Someone asked, “What’s the matter, are they knocking the boys too hard?”

“No, not that,” Thompson said. “But I just want to show some of those so-called big fellows back home they can’t play peanut politics with me.”50

But Mellon refused to budge, prompting Fred Mann to abandon his legal fight to save Rainbo Gardens. In early May, Mann and his attorney agreed to a consent decree, padlocking the venue for a year. “What’s the use?” Mann said, shrugging his shoulders. His surrender spelled doom for another 12 Chicago establishments facing injunctions,51 including Colosimo’s52 and Midnight Frolics.53 As the Tribune explained, it was now “the law of the land for Chicago” that any place allowing people to bring in their own alcohol was considered an illegal public nuisance.54 An International News Service report predicted this would be the end of Chicago’s “tottering night life.”

“Now that [Mann] has capitulated before the government enforcement juggernaut, owners and proprietors of the tinseled palaces admit the outlook is dark,” the article said. “… Within two weeks, it is believed, Chicago’s once gay night life will be definitely a thing of the past.”55

In addition to injunctions shutting down a dozen of Chicago’s most famous nightclubs, more than 300 other places had been padlocked in the previous year, including beer flats, soft drink stands, pool rooms, and restaurants. And 475 additional cases were pending. The Associated Press predicted that many Chicagoans would go outside the city limits for their nightlife, drinking at suburban roadhouses and “chicken dinner farms.” Authorities said more than 125 roadhouses had opened recently in Cook County outside Chicago.56

The Tribune reported that New York City’s cabarets still seemed to be going full-blast, even while the feds shut down Chicago’s. A reporter asked the owner of a popular New York nightclub: “How do you get by with it? They are closing up Chicago.”

“That’s easy,” the proprietor said. “You see, the underworld took up so much room out there they couldn’t build any subways. We’ve already got our subways here.”57

Federal authorities confirmed that they’d been focusing on Chicago. During the month of May 1928, the feds had seized 69,963 gallons of beer nationwide—85 percent of it in Chicago. Out of all the liquor seized nationwide, 54 percent was snatched by the feds in Chicago. And a majority of the nation’s court injunctions shutting down places for violating prohibition laws were issued in Chicago.58

Later that summer, the Belleville Daily News-Democrat expressed skepticism about all of these obituaries declaring the death knell of Chicago’s nightlife. The downstate newspaper’s headline said: “Padlocks? Ha! Ha!”

This article reported that the young female entertainers who’d attracted men to attend Chicago’s cabaret were now performing elsewhere. “Many … have gone over to vaudeville,” the story said. “… Some of them have been engaged as entertainers at home parties. … Every little group of friends in certain circles now has its own ‘night club.’ Many of them, formerly patrons at cafes and night clubs downtown, now give weekly or semi-weekly parties in home apartments and bachelor flats, and ‘divvy’ up the bill.”59

As Rainbo Gardens shut down on May 6,60 the company was in dire financial straits, with $995,000 in debts (roughly $18 million in 2024 dollars).61

But the building didn’t remain dark for long: A wholesale jeweler, J.L. Art, leased it, asking the federal court for permission to operate it as a convention hall and ballroom, hosting fashion shows, auto shows, trade shows, concerts, boxing exhibitions, athletic tournaments, and “other lawful purposes.”62 Prosecutors opposed the plan, arguing that the venue would continue to attract drinkers. George E.Q. Johnson pointed out that Rainbo had “gained notoriety as a public drinking resort where the Federal Prohibition Law was completely and held for naught.”63 But a judge agreed to let Rainbo reopen as a convention hall.64

The adjacent Rainbo Fronton continued to host jai alai games—until authorities closed the loophole that had allowed gambling.65 By the summer of 1929, Chicago’s jai alai fad was over.66

Rainbo Gardens went into receivership. Stockholders accused Mann of misusing the company’s money and property. Among other things, they alleged that he’d taken ginger ale, meats, poultry, and foodstuffs from Rainbo to his summer home.67 The company was also facing a mortgage foreclosure, involuntary bankruptcy proceedings,68 and several lawsuits.69

As Mann was dealing with all of this litigation, he was robbed inside his Rainbo office on the morning of June 12, 1929, shortly after he arrived from his nearby home (at 4750 North Dover Street).

“I had been sitting there not more than five minutes when two men, one of them tall and one of them of medium height, stepped into the office,” Mann said. “The tall fellow had a gun and he stuck it in my ribs. ‘Take it easy, Fred,’ he said, ‘and there won’t be any jam.’”

After taking money from Mann’s pockets, the robbers noticed his ring and stickpin. “‘Guess we’ll have to take those,’ he said, and grabbed them,” Mann recalled. “They stood for a minute and then one of them said, ‘How about opening the safe?’ I told them there wasn’t any money in the safe, which was the truth. They looked around then, grabbed some pieces of rope that were lying about and made me lie on the floor. They tied me up, told me not to make any noise, and ran out the door.”70

By this time, the court injunction closing Rainbo Gardens for a year had expired, creating an opportunity for the place to reopen. Mann’s company sold the property to a new business entity called Uptown Enterprises Inc. on October 24, 1929.71 Five days later, the “Black Tuesday” stock market crash threw the nation into economic turmoil.

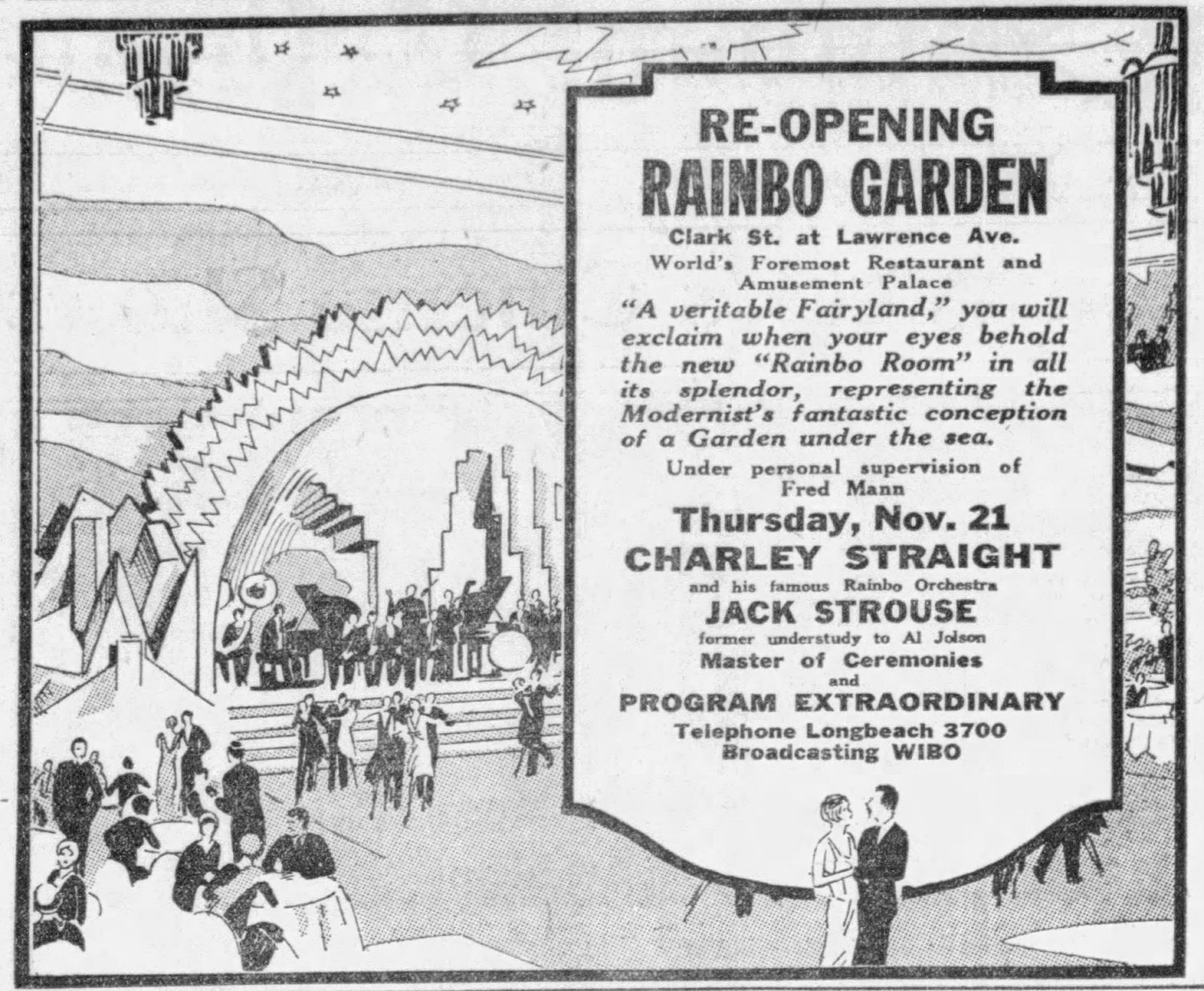

Mann stayed on as the venue’s manager. After $100,000 in remodeling,72 it reopened on November 21, billing itself as the “World’s Foremost Restaurant and Amusement Palace.” According to an advertisement: “‘A veritable Fairyland,’ you will exclaim when your eyes behold the new ‘Rainbo Room’ in all its splendor, representing the Modernist’s fantastic conception of a Garden under the sea.” A bandleader who’d played often at the Green Mill, Charley Straight, provided the music for Rainbo’s reopening, performing with “his famous Rainbo Orchestra.”73 Afterward, the Daily Times reported: “Under the guidance of Fred Mann, the old place blossomed forth with more than past splendor and the modernistic garden and fairyland were a riot of color.”74

But a few weeks later, a fire broke out in Rainbo Gardens one afternoon, as scantily clad chorus girls and “show folk” rushed out into the street in the midst of their rehearsals. The fire, which was blamed on crossed electric wires, caused an estimated $50,000 in damage, wrecking the roof, the ballroom, and the remodeled restaurant.75

Rainbo apparently remained dark for most of the following year, though boxing exhibitions were announced in the adjacent Rainbo Fronton.76 At the end of August 1930, Rainbo Gardens began hosting a dance marathon, along with four other endurance contests, testing how long people could fiddle, play a piano, walk, or sit in a rocking chair. “Nothing like it ever before attempted,” an ad said. “Dance as long as you like.”77

Dance marathons were a national craze at the time. Typically, participants had to remain upright and moving for 45 minutes out of each hour, around the clock. These endurance competitions took on a tone of desperation as the Great Depression threw millions of Americans out of work. The events typically provided contestants with free meals, and the cash prizes they offered were sometimes equivalent to a year’s salary. And watching these seemingly endless events gave people something to do.78

Earlier in 1930, Chicago city officials had talked about stopping these contests. “Marathon dances come within the statutory definition of the crime of ‘riot,’ and those who assemble to take part in a marathon dance are guilty of unlawful assembly,” the city’s corporation counsel advised. “The Superintendent of Police has power to prevent and disperse an unlawful assembly.” The lawyer also added: “Those in charge of a marathon dance are guilty of violating the Women’s Employment act if they permit any woman to dance for more than ten hours in any twenty-four hour period.”79 But the police apparently did not follow through with any raids.

On August 7, two dancers set a new world record at the Merry Garden ballroom, at Belmont and Sheffield Avenues. Ann Gerry and Mike Gouvas finally stopped after dancing for 2,831 hours and 4½ minutes.80 According to the Chicago-based Ladas Malted Raisin Company, “this young couple have been maintaining their strength and energy with frequent drinks of Malted Raisins, the delightful new malted concoction.”81

Now, the marathon at Rainbo Gardens was offering $5,000 to any couple who broke that record—in addition to $2,000 for first place, $500 for second place, and $200 for third place. One contestant walked 26 days from Los Angeles before joining in the competition.82

A week into the marathon, one of the dancers, Claire Decore Herdich, paused long enough to give an interview to the Daily Times. The 17-year-old was already in the news because her husband, the heir to a liquor fortune, was suing her for divorce. “I love the world too much to be the wife of any man,” she said. “Love? You ask me what I think of love? Why, you really do not believe in such absurdities, do you?”83

As September turned to October, more than a dozen couples were still dancing at Rainbo Gardens. (The outcomes of the fiddle, piano, walking, and rocking chair marathons are unknown.)

By this time, Fred Mann was no longer the owner or manager of Rainbo Gardens. A court decree had dissolved his corporation, the Rainbo Garden Company, in June.84 He’d lost control of the entertainment palace he’d made famous.

Content warning: The next portion of this chapter discusses suicide. If you or someone you know is suicidal, please contact your physician, go to your local ER, or call the suicide prevention hotline—988 in the U.S.

On the afternoon of October 8, 1930, Fred Mann sat down on a bench in Lincoln Park near Webster Avenue, facing toward a stream of automobiles passing by on Lake Shore Drive. At 4:40 p.m., someone strolling nearby heard a gunshot. Mann was found on the bench with a revolver at his side. He’d shot himself in the head. One of his business cards was in the palm of his half-closed left hand, with a handwritten message on it: “Please remove my body to George Klaner’s undertaking rooms, 4714 Broadway. Good-by, George. Take care of everything. Notify Al.”

“Al” was a reference to his son. Al Mann said his father had showed no signs of despondency and hadn’t seemed worried about his health or finances. Fred’s widow, Rose, and his brother, Gustave, said they were puzzled by his suicide. But the next morning’s banner headline across the Tribune’s front page suggested that Fred Mann must have been depressed about the fate of his famous business: “RAINBO LOST, MANN ENDS LIFE.”85

Mann, a Jewish immigrant86 from Berlin, was 56 years old.87 A coroner’s jury found that he’d been “temporarily insane” after feeling “despondent at intervals since he lost control of the Rainbo Gardens,” the Tribune reported.

“There is no other way out for me,” Mann told his son, in a letter that he’d left for his family. “Am afraid I am going insane. Forgive me—it is all my own fault.” Addressing his wife in the letter, Mann wrote: “I am going insane seeing you suffer from my misfortunes. Had I only listened to you, all would have been different. Have mercy on me.”88

At 11 p.m. on the day of Mann’s death, the music ceased for one minute in the dance marathon at Rainbo Gardens, as 14 teams of weary dancers paused.89

“The orchestra ceased to play, the crowd sat, hushed,” the Daily Times reported. “The endurance dancers halted, tired arms dropping at their sides. Masseurs, trainers, foot doctors and the other entourage of the non-stop terpsichore lolled, silent, in the background.

“The jazz age was paying tribute to Fred Mann. Sixty seconds of silence, then the tap of the leader’s baton. Strike up the band! On with the everlasting dance!”90

Ten days later, nine couples were still dancing in the marathon. But one by one, everyone else at the venue seemed to disappear. The dancers’ trainers were gone. The judges left. The orchestra stopped playing and packed up. “But still the valiant marathoners kept on—until the dinner hour when they discovered the cook had gone,” the Tribune reported. “There was nothing to eat. They stopped dancing. They were too weak to continue.”

They’d danced a total of 1,160 hours over 50 days. But it quickly became apparent that none of them would win any money for their laborious efforts. A private detective showed up, locking the doors of the Rainbo Gardens ballroom. “It’s all because one of the promoters has vamoosed, and there’s going to be court action,” he said.

Most of the couples who’d been dancing went into the lobby and fell asleep. One contestant telephoned the Tribune. “They’re sleeping there now because they haven’t any money for room rent,” he said. “Something should be done about it. We’re all hungry. Can you beat that? Me and my girl were planning to win that $5,000 purse, get married, and take a trip to Europe. And now we get the bum’s rush—”

Interrupting, a telephone operator said: “Your five minutes is up; another nickel please.”

“Good-bye, Tribune,” the contestant said. “That was my last jitney.”91

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

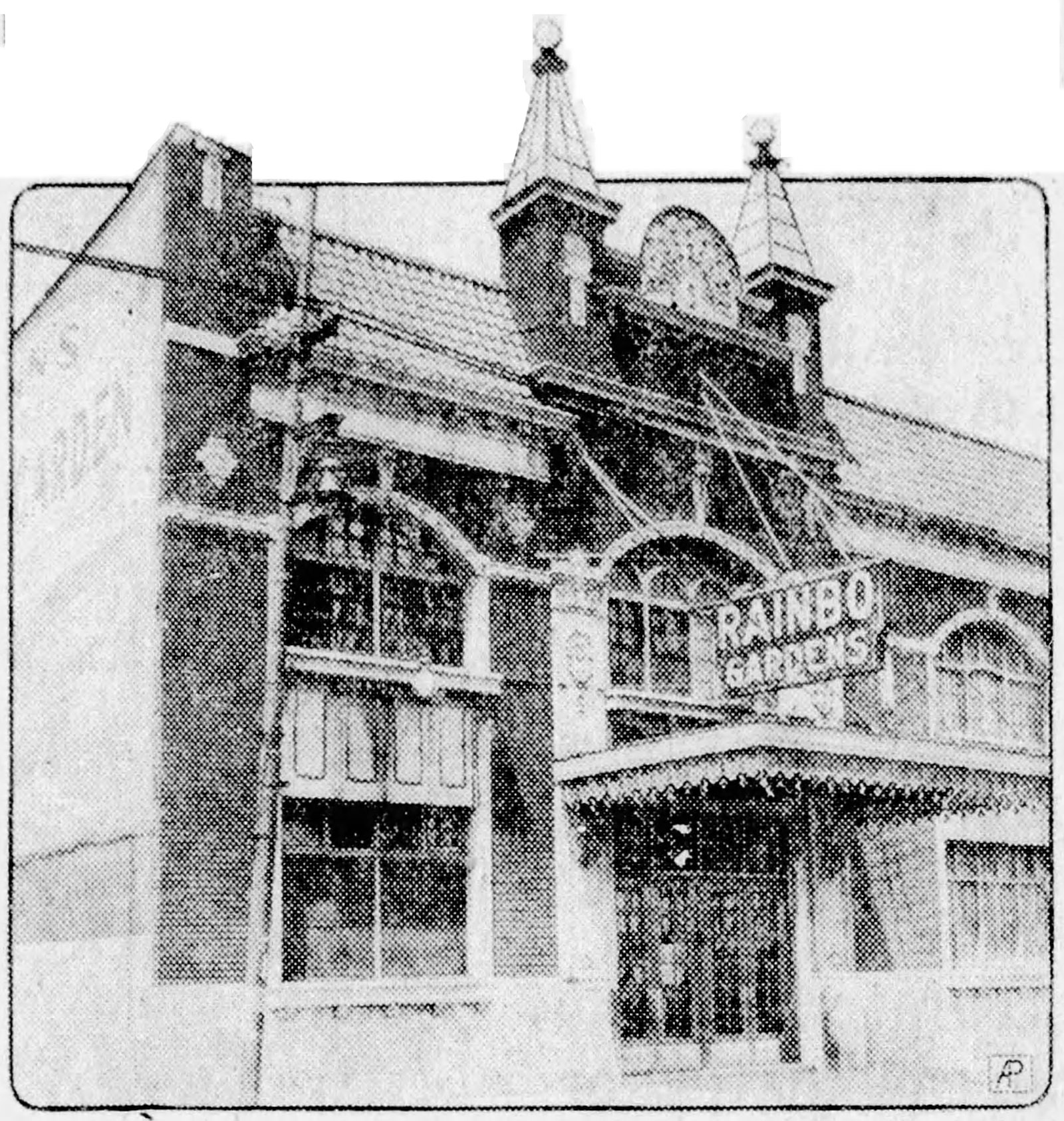

The photo at the top of this chapter: Mann’s Million Dollar Rainbo Gardens, circa 1927. Postcard A113906. Curt Teich Postcard Archives Collection, Newberry Library.

Footnotes

1 “Big Thompson Crowd Sinks Fish Fans’ Club,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 6, 1927, 1; Associated Press, “Hundreds of Padlocks Drive Night Life From Chicago Into Country,” (Belleville, IL) Daily Advocate, June 6, 1928, 8.

2 John Bright, Hizzoner Big Bill Thompson: An Idyll of Chicago (New York: J. Cape & H. Smith, 1930), 208, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t7jq25k3t?urlappend=%3Bseq=236.

3 “Thompson Wants Office Monday,” Chicago Daily News, April 7, 1927, 1, 3.

4 “Blanket Raid Covers Chi Cafes With No Search Warrants Used,” Variety, February 8, 1928, 55, https://archive.org/details/variety90-1928-02/page/n117/mode/2up.

5 Charles A. Sengstock, That Toddlin’ Town: Chicago’s White Dance Bands and Orchestras, 1900–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2004), 132–133.

6 “Current Entertainment,” Chicagoan, July 2, 1927, 3. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v003-i08/mvol-0010-v003-i08.xml#page/5/mode/1up.

7 “Current Entertainment,” Chicagoan, August 27, 1927, 4. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v003-i12/mvol-0010-v003-i12.xml#page/6/mode/1up.

8 “Padlock for Rainbo Dooms Night Clubs,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 4, 1928, 1.

9 “Rob Fred Mann in Rainbo Office,” Chicago Daily News, June 12, 1929, 1.

10 Anonymous (John Corbett, ed.), Bullets for Dead Hoods: An Encyclopedia of Chicago Mobsters, c. 1933 (Chicago: Soberscove Press, 2020), 137–138.

11 “Joey Burman Is Shot in Mystery,” Chicago Daily News, June 11, 1928, 3.

12 “Renew Battle Over Catering at Navy Pier,” Chicago Daily News, May 4, 1929, 15; “Personal Paragraphs,” Daily National Hotel Reporter, October 11, 1930, 1.

13 “Plague of $5 Dinners Makes City Hall Tired,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 6, 1928, 1, 2.

14 “Rainbo Garden Stockholders Ask Receiver,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 16, 1929, 18.

15 “Gamblers Thrive Under New Plan,” Chicago Daily News, July 25, 1927, 1, 4.

16 “Gambling Trust Boasts of Power,” Chicago Daily News, August 20, 1927, 5.

17 “Capone Calls Parleys in Fight to Retain Gang Power,” Chicago Daily News, November 29, 1927, 1, 3.

18 “Renew Gambling Under New Deal,” Chicago Daily News, December 22, 1927, 3.

19 Will Leonard, “Tower Ticker,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 21, 1951, 33.

20 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6, 1928, 10.

21 Rainbo Exhibition Company corporation papers, Secretary of State (Corporations Division): Dissolved Domestic Corporation Charters, 103/112, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

22 Mexican Joe, “Chicago’s Brand of Jai Alai Looks Like Real Thing,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 22, 1927, 19.

23 Will Leonard, “Tower Ticker,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 21, 1951, 33.

24 Charles Collins, “The Low-Down on Jai Alai,” Chicagoan, February 11, 1928, 13. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v004-i10/mvol-0010-v004-i10.xml#page/15/mode/1up.

25 “Al Jolson Rushing Here to Fill Vacancy in Revue,” Chicago Daily Tribune March 10, 1928, 7; Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, April 5, 1928, 37.

26 “Grand Opera House (Chicago),” Wikipedia, accessed January 8, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Opera_House_(Chicago).

27 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, March 23, 1928, 37.

28 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6, 1928, 10.

29 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, November 24, 1927, 45.

30 Fritzel v. United States, Circuit Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, March 23, 1927, 17 F.2d 965 (7th Cir. 1927), https://casetext.com/case/fritzel-v-united-states.

31 “Chicago Hip Flasks on Way to High Court,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1927, 1.

32 “Padlocks Over Hip Rum Upheld,” Detroit Free Press, October 18, 1927, 10.

33 “U.S. Forces Get Ready to Swing Mop in Chicago,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Oct. 20, 1927, 1.

34 “Padlocks Over Hip Rum Upheld,” Detroit Free Press, October 18, 1927, 10.

35 Affidavit of Frederick D. Silloway, February 6, 1928, Equity 7836, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens Company and Fred Mann, U.S. District Court for the Eastern (Chicago) Division of the Northern District of Illinois, National Archives at Chicago.

36 Affidavit of George A.E. Williams, February 6, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

37 Affidavit of Louis F. Cole, February 6, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

38 Affidavit of John L. Smysor, February 6, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

39 Answer of George E.Q. Johnson, May 21, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

40 “Bright Spots of City’s Night Life Raided,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 5, 1928, 1.

41 John C. Thomas, “Chicago’s Transportation Building—Former Headquarters of Eliot Ness and The Untouchables,” HubPages, updated January 3, 2018, https://discover.hubpages.com/education/Chicagos-Transportation-BuildingFormer-Headquarters-of-Eliot-Ness-and-The-Untouchables.

42 “Blanket Raid Covers Chi Cafes With No Search Warrants Used,” Variety, February 8, 1928, 55, https://archive.org/details/variety90-1928-02/page/n117/mode/2up.

43 Exhibit A: affidavit of R.M. McNaught, February 7, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

44 “Bright Spots of City’s Night Life Raided,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 5, 1928, 1.

45 “Padlocks Loom for 12 Cabarets,” Chicago Daily News, February 6, 1928, 6.

46 “Blanket Raid Covers Chi Cafes With No Search Warrants Used,” Variety, February 8, 1928, 55, https://archive.org/details/variety90-1928-02/page/n117/mode/2up; “Mann on Way to Lead Defense in Padlock War,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 7, 1928, 5.

47 “12 Chi Padlocks and Now It’s Too Late,” Variety, February 15, 1928, 54, https://archive.org/details/variety90-1928-02/page/n181/.

48 Answer of defendants, February 25, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

49 “Thompson Has Plan to Draft Coolidge,” New York Times, February 25, 1928. https://www.nytimes.com/1928/02/25/archives/thompson-has-plan-to-draft-coolidge-chicago-mayor-will-ask-for-cook.html.

50 H.B. Gauss, “Mayor Registers Kick With Mellon,” Chicago Daily News, February 25, 1928, 6.

51 Gene Hoffman, I.N.S., “Chicago’s Oasis Celebration Ends With Padlockings,” Waukegan Daily Sun, May 4, 1928, 16.

52 “Court Indicates He Will Padlock Colosimo’s Cafe,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 10, 1928, 11.

53 “Year’s Padlock Put on Midnight Frolics Cabaret,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 23, 1928, 18.

54 “Padlock for Rainbo Dooms Night Clubs,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 4, 1928, 1.

55 Gene Hoffman, International News Service, “Chicago’s Oasis Celebration Ends With Padlockings,” Waukegan Daily Sun, May 4, 1928, 16.

56 Associated Press, “Hundreds of Padlocks Drive Night Life From Chicago Into Country,” (Belleville, IL) Daily Advocate, June 6, 1928, 8.

57 Tom Pettey, “Liquor Clubs Run Wide Open in New York,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 14, 1928, 1.

58 “U.S. Rum War Centers Upon Chicago Oases,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 20, 1928, 3.

59 Ione Quinby, “Padlocks? Ha! Ha!,” Belleville (IL) Daily News Democrat, Aug. 14, 1928, 2.

60 Answer of George E.Q. Johnson, May 21, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

61 Petition of Rainbo Gardens and Fred Mann, May 10, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

62 Petition of J.L. Art, May 28, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

63 Answer of George E.Q. Johnson, May 21, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

64 “Rainbo Garden to Be Reopened as Exposition,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 29, 1928, 10; Order for temporary injunction, May 28, 1928, U.S. v. Rainbo Gardens.

65 R.N. Knox, “Sell Jai-Alai Certificates Despite Legal Ban,” (Chicago) Collyer’s Eye, May 25, 1929, 3.

66 Will Leonard, “Tower Ticker,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 21, 1951, 33.

67 “Rainbo Garden Stockholders Ask Receiver,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 16, 1929, 18.

68 “Rainbo Gardens Named in Bankruptcy Action,” Chicago Daily News, February 14, 1929, 5.

69 Tract book 541B, 268, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

70 “Rob Fred Mann in Rainbo Office,” Chicago Daily News, June 12, 1929, 1.

71 Tract book 541B, 268, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

72 “Rainbo Garden Sold; Will Be Reopened Nov. 21,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 1, 1929, 28.

73 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, November 17, 1929, part 7, 2.

74 “With the Cabarets,” (Chicago) Daily Times, Nov. 23, 1929, p. 23.

75 “Rainbo Gardens Fire Perils Actors; $50,000 Damage,” Chicago Daily News, December 14, 1929, 1.

76 Wade R. Franklin, “Now Boxing Dolls Up in Soup ‘n’ Fish,” Chicago Daily News, January 14, 1930, 24.

77 Advertisement, (Chicago) Daily Times, August 30, 1930, p. 22.

78 “Dance Marathon,” Wikipedia, accessed January 10, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dance_marathon.

79 Barnet Hodes, ed. and compiled, Opinions of the Corporation Counsel and Assistants, Vol. 18, April 15, 1929 to December 31, 1935, (Chicago: City of Chicago Law Department, 1936), 436–437, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112102875913?urlappend=%3Bseq=468%3Bownerid=13510798901453720-484.

80 “Swollen Ankle Ends Dance at 2,831st Hour,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 8, 1930, 1.

81 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 17, 1930, 7.

82 “Here’s a Story Without Any Happy Ending,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 19, 1930, 1.

83 Patricia Palmer, “Love? There Isn’t Any, Declares Bride in Dance Marathon Sued by Young Heir,” (Chicago) Daily Times, September 6, 1930.

84 The Rainbo Garden Co. corporation papers, Secretary of State (Corporations Division): Dissolved Domestic Corporation Charters, 103/112, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

85 “Rainbo Lost, Mann Ends Life,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 9, 1930, 1, 2.

86 “Decide Mann Killed Himself While Insane,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 10, 1930, 26.

87 “Fred Mann,” Find a Grave, accessed June 17, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/161625510/fred-mann.

88 “Decide Mann Killed Himself While Insane.”

89 “Rainbo Lost, Mann Ends Life.”

90 “Dancers Halt as Tribute to Fred Mann,” (Chicago) Daily Times, October 9, 1930, 2.

91 “Here’s a Story Without Any Happy Ending,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 19, 1930, 1.