Chapter 7 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER—>

Around 1913, as Tom Chamales began making plans to transform the old Morse’s roadhouse into the larger and more lavish Green Mill Gardens, some people wanted the surrounding neighborhood to stay “as orderly as a country village.”1 Chamales had different ideas.

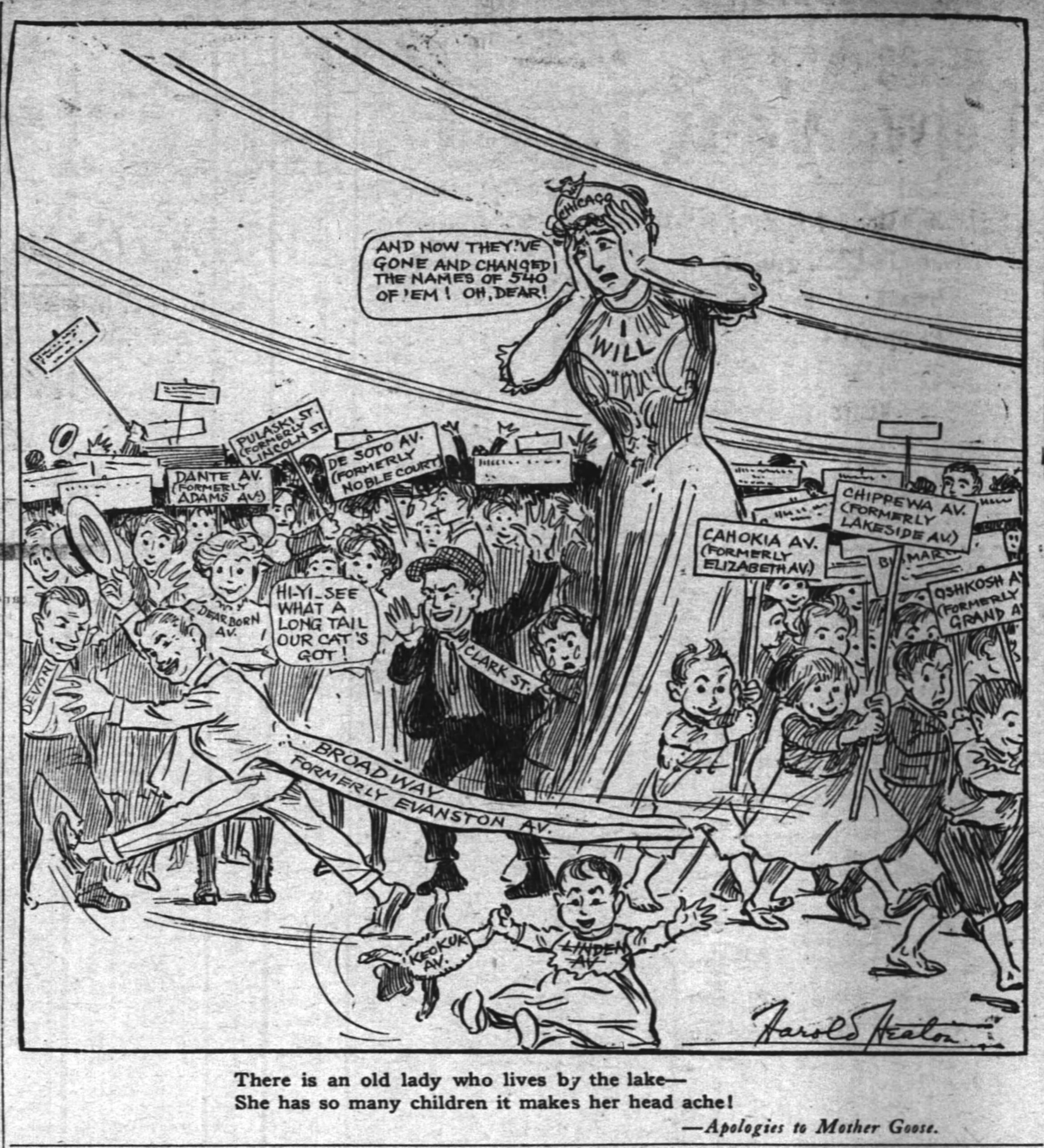

So did other men who owned businesses along Evanston Avenue. They lobbied the city to change the street’s name. Reportedly, local saloonkeepers worried that “Evanston Avenue” made people think of Evanston, a dry town just north of Chicago. That wasn’t the image these bar owners wanted for their street. Businessmen persuaded city officials to give it a new name—a moniker that evoked New York City’s famous theatrical district. At the end of the day on August 14, 1913—at the stroke of midnight—Evanston Avenue became Broadway.2

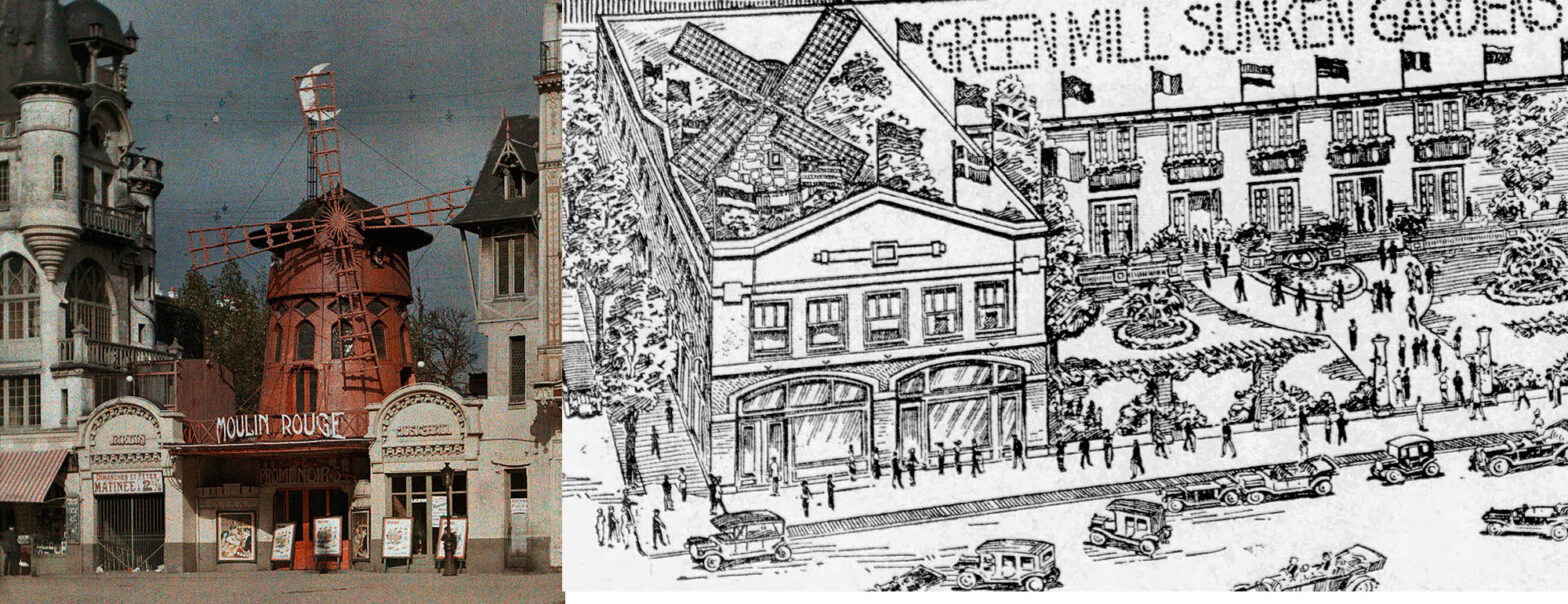

A cartoon about Evanston Avenue being renamed Broadway, from the August 16, 1913, Inter Ocean. Courtesy of Bill Savage.

But when Chamales chose a name for his new entertainment palace on Broadway, he seemed to have Paris on his mind, not New York. “Green Mill Gardens” was clearly inspired by a legendary Paris cabaret that opened in 1889, the Moulin Rouge—a name that’s French for “red mill.” The Moulin Rouge famously had a windmill on its roof, and so did Green Mill Gardens. That is surely no coincidence.

It’s unknown exactly when Chamales chose to call it Green Mill Gardens, or why he chose green as part of the name. When he signed a new lease on February 28, 1913, it gave him the right to use the name “Morse” for the business. He may have planned to continue using that name. The property’s owner—Pop Morse’s daughter, Catherine Hoffman—and her husband agreed that they wouldn’t use the Morse name for any business of their own. If they did, they would owe Chamales $10,000.3 A month later, the New York Clipper reported that Chamales was going to call his new venue the Red Mill. The newspaper may have simply made an error about that, or perhaps Chamales later changed his mind about the name.4

In the following years, another venue in the neighborhood was briefly known as the Moulin Rouge, before changing its name to Rainbo Gardens. In 1918, a movie theater opened across the street from Green Mill Gardens with French-style architectural elements and a name that alluded to a resort area in France and Italy: the Riviera. And in 1919, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that some people were calling the Wilson Avenue District—as the neighborhood was commonly known—by the nickname “Little Paris.”5 A few years later, Green Mill Gardens would be taken over for a while by the Montmartre Cafe, which was named after the Paris nightlife district around the Moulin Rouge. It’s clear that Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood had a Paris thing going on—or maybe it was just that some Chicagoans imagined it was their local version of Paris.

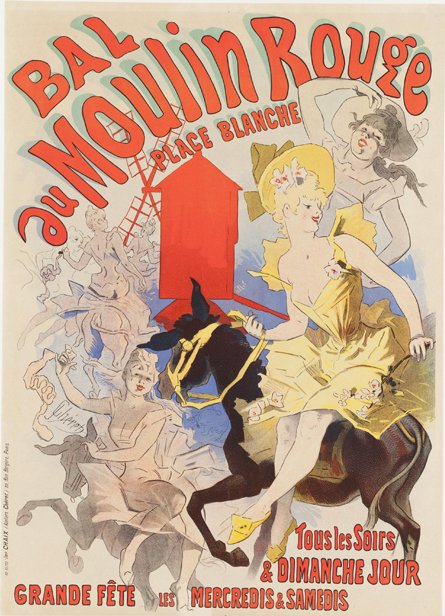

Why would anyone in Chicago care about—or even know about—a nightclub in Paris? It’s rather remarkable just how famous the Moulin Rouge was, at a time when only the wealthiest Americans could afford a vacation in Europe. When the Moulin Rouge opened in 1889—the same year the Eiffel Tower was completed, amid a world’s fair in Paris—it was long before radio, television, and social media existed, of course. Even photographs were a rarity in newspapers at the time. But the Moulin Rouge seemed to dance in the imaginations of many Americans who’d never set eyes on it, a symbol of the nightlife in Paris, both sophisticated and sexy.

Jules Chéret’s 1889 lithograph Bal du Moulin Rouge. Milwaukee Art Museum.

American newspapers began publishing reports about the Moulin Rouge as soon as the place opened.6 In 1891, a Paris correspondent for the Tribune, Theodore Child, wrote about “the joyous Moulin Rouge,” calling it “the favorite bachelors’ promenade in Paris and the grand conservatory of transcendental choreography.”7 And in 1892, a “very estimable lady” in Chicago society confessed that she’d visited the Moulin Rouge, wearing a veil to conceal her identity as she went inside the Paris cabaret. “I should not have gone, but I did; and—isn’t it bewitchingly naughty?” she blushingly told a writer for the Inter Ocean.8

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1892–95 painting At the Moulin. Art Institute of Chicago.

The Moulin Rouge was especially famous for its rows of female dancers performing the cancan, kicking up their skirts and revealing their stocking-clad legs. (The Moulin Rouge management reportedly didn’t permit dancers to perform in “revealing undergarments” such as pantalettes, which had an open crotch.)9

Marius Bauer’s 1891 drawing Danseres in de Moulin Rouge, Rijksmuseum.

“It was primarily a music hall, a showcase for revues, rather than a dance hall proper (at least after 1900); it was explicitly intended for the slumming rich; and the cancan was already old news by the time it opened in 1889, for all that it has ever claimed to be its birthplace,” Lucy Sante wrote in The Other Paris. “Still, the Moulin Rouge is worth noting for the quality of its terpsichoreans, many of them painted by Toulouse-Lautrec…”10

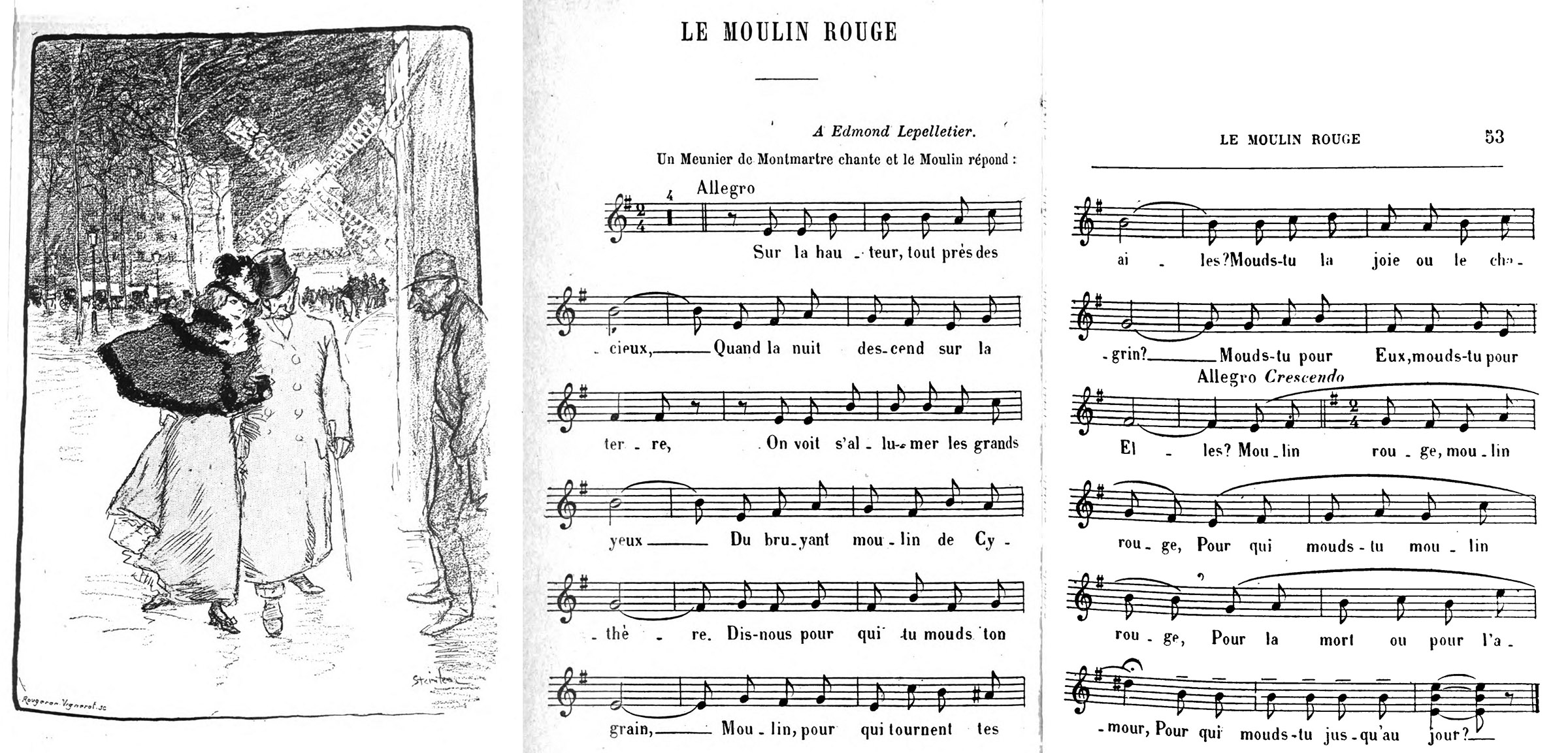

An 1896 song titled “Moulin Rouge” questioned the purpose of the mill on the building’s roof (a question Chicagoans may well have asked about Green Mill Gardens 18 years later). The song directs a query at the cabaret: “Tell us who you grind your grain for.” The Moulin Rouge answers by describing itself as a place of respite for laborers, dwarves, fools, assassins, the poor, the sick, and the hungry, helping them in “forgetting that their bellies growl” and to “get drunk on endless rhythms and visions of blond flesh.”11

Chicago’s Inter Ocean mentioned that song when it reprinted a London newspaper’s report about the “continuous” stream of people entering the Moulin Rouge in 1900. “When the bands start and the dancing begins there is a stampede,” the dispatch said.12 Paris was hosting another world’s fair that year, and an estimated 7,500 Americans (one out of every thousand people) crossed the Atlantic to attend.13 The Tribune told Chicagoans about U.S. officials refusing to let tourists mail “indecent souvenir cards sold about the exposition representing wild Moulin Rouge scenes and other features of Paris night life.”14

Stage shows in Chicago began to feature female dancers billed as “Moulin Rouge Girls.” Reviewing a 1905 show at McVicker’s Theatre, Inter Ocean critic Burns Mantle wrote about one such set of dancers: “They are attractive young women, who, among other things, lie on their backs, elevate their black-stockinged walkers, and execute several imaginary steps in this position.”15

It’s easy to see why Chamales would want to remind Chicagoans of the Moulin Rouge when he chose the name of his new venue. He may have been trying to tantalize them with the hope that they might experience something like the risqué Parisian nightlife they’d heard so much about.

As he demolished Pop Morse’s roadhouse and built Green Mill Gardens, he was following trends in Chicago’s entertainment venues: the rise of amusement gardens and cabarets, and the craze for dancing.

City of Gardens

Beer gardens were popular in Germany, so it was natural that they’d catch on in Chicago, with its large population of German immigrants. By 1895, the Sunnyside Inn at the northeast corner of Clark Street and Montrose Avenue was calling itself Sunnyside Park and hosting large outdoor concerts.16

Bismarck Gardens opened in 1895 at the southwest corner of Grace and Halsted Streets, taking over a place called De Berg’s Grove. By the late 1890s, Manila Garden, Simon’s Grove, and Biewer’s Garden were operating on Clark Street in the blocks just north of the Sunnyside.17 Some of these venues closed around the turn of the century, but Bismarck Gardens continued to be the city’s most popular beer garden. The property, which was owned by Anheuser-Busch Brewing from 1900 to 1911, had a capacity of more than 4,000, with an outdoor stage and dance floor, serving up German beer and music.18

In 1904, Ravinia Park opened in Highland Park as a high-end amusement park with a music pavilion, a dance hall, a baseball stadium, and a theater. It was designed as a lure for Chicagoans to ride the Chicago and Milwaukee Electric Railroad into the north suburbs.19

“In the early teens Chicago hosted a wide range of summer entertainment gardens for all tastes and classes,” Paul Kruty wrote in a 1987 Chicago History magazine article. “Local beer halls abounded, often with a few tables in back. Several beer gardens, however, were elaborate affairs.”

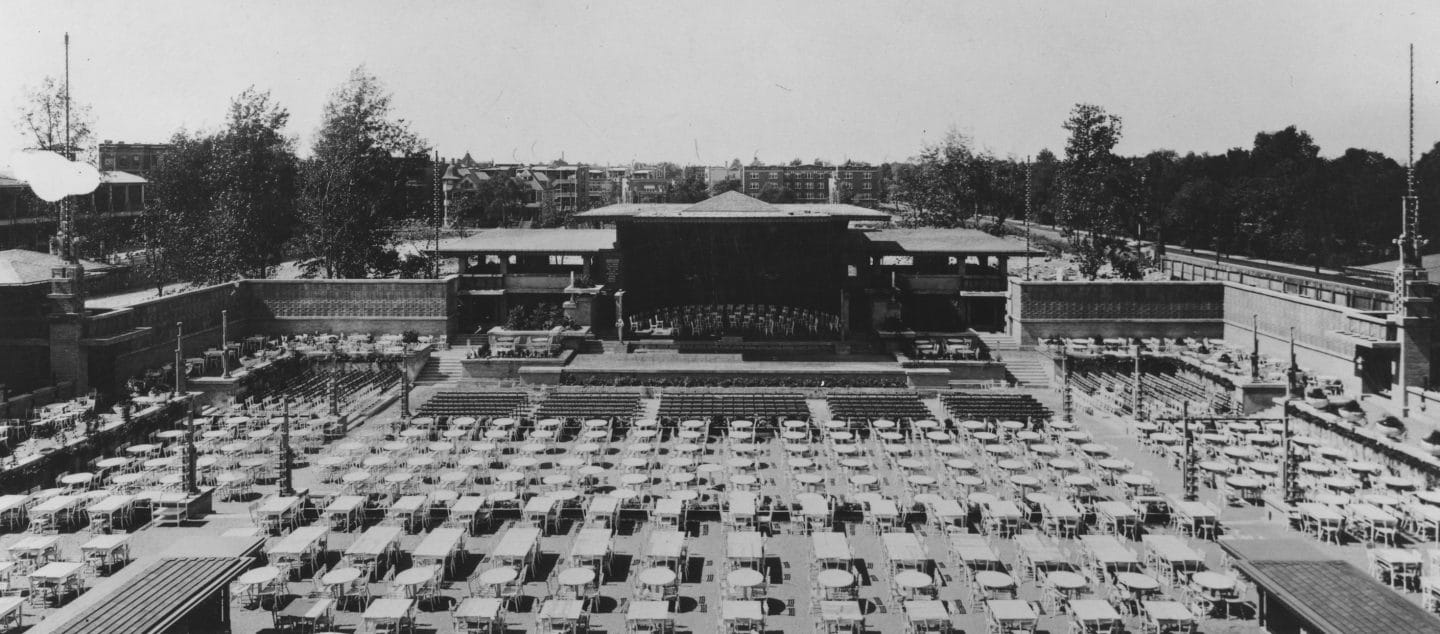

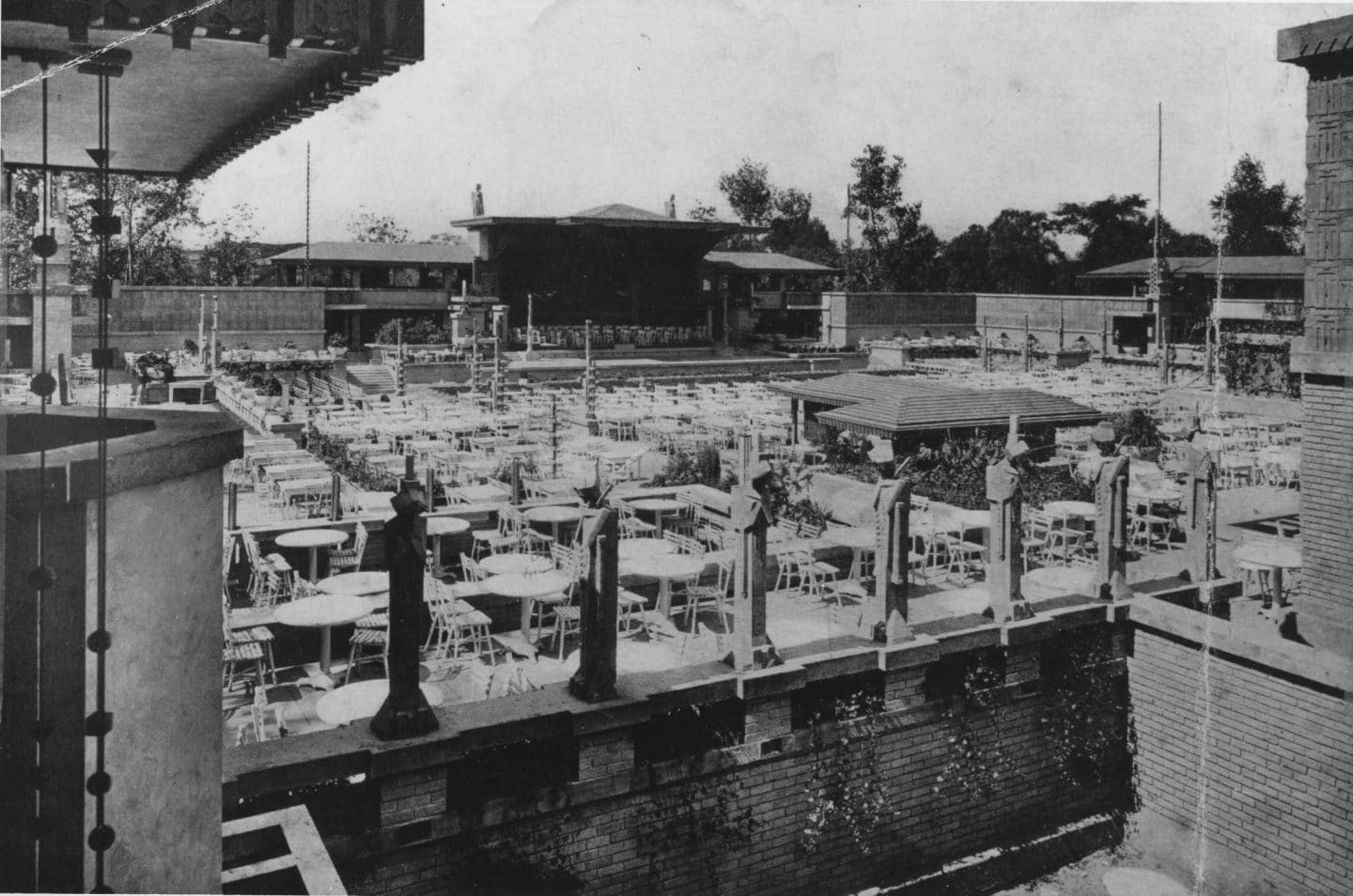

One of the more elaborate places was the South Side’s Midway Gardens, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. It opened in 1914, with a pavilion on the west side of Cottage Grove Avenue south of 60th Street.

Midway Gardens. Photos from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

“Midway Gardens was planned to combine the best elements of all these parks—formal and informal dining, public bar and private club, background music and serious classical concerts,” Kruty wrote. Midway Gardens held its first trial concert on June 20, 1914, followed by the official opening on June 27, attracting crowds of more than 17,000. Green Mill Gardens opened the same month. Facing all of this new competition, Bismarck Gardens added a 50-piece orchestra that summer.20

Come to the Cabaret

Like these other big entertainment complexes, Green Mill Gardens was not just a garden. It also had interior spaces for dining and drinking, as well as an indoor stage for performances. This indoor space was known as a cabaret—a type of venue that was growing in popularity in Chicago and other U.S. cities.

As the 20th century began, Chicagoans could experience live music in theaters, concert halls, and parks. Piano players and other musicians entertained visitors at Chicago’s brothels,21 while small orchestras performed at dance halls and ballrooms.22 Some of the city’s bars were known as “concert saloons,” featuring performances of music such as ragtime.23 Some reformers saw live music as a part of the sinful saloon culture. City officials (including mayor Carter H. Harrison and police superintendent Francis O’Neill) tried to ban musical performances in saloons, but the music always came back after the police raids subsided.24

The cabaret movement began in the cafés of Paris and Berlin, before spreading to the United States.25 These venues featured live music and theatrical skits and other performances in a small space where food and drinks were served. “They were places of spectacle, but also places of intimacy where people could smoke, eat, drink, and be entertained,” Katherine Anne Yachinich wrote in her 2014 thesis, “The Culture and Music of American Cabaret.” 26

“Chicago was really the leader in the beginning of that kind of entertainment in the United States,” Charles A. Sengstock Jr., the author of That Toddlin’ Town: Chicago’s White Dance Bands and Orchestras, 1900–1950, told me in a 2020 interview. “It set up a feeling of intimacy between the entertainer and the audience that could not be realized in a theater.”

“Professional singers or dancers backed by small bands or combos performed directly in front of seated or dancing audience members mere yards way,” Derek Vaillant wrote in Sounds of Reform: Progressivism and Music in Chicago, 1873-1935. “The intimacy of the experience for audiences derived from the human scale of the room and the close proximity of spectators to the stage where singers and musicians sweated over their art or dancers shook their bodies. … Performers frequently left the stage to continue their acts among the dancing audience or ad-libbed comments during songs in response to audience activity in front of them. Female singers roamed the aisles, touching patrons, flirting with them, even bringing them up on stage to become part of the show.”27

Jack Johnson, the first Black world heavyweight boxing champion, opened one of Chicago’s earliest cabarets, Cafe de Champion,28 at 41 West 31st Street in the South Side’s Black Belt in July 1912. Known as a “black and tan,” it was open to both white and Blacks patrons. It attracted large crowds and much press coverage, but stayed open for only a few months.

After Johnson was arrested on trumped-up charges of violating the Mann Act—for allegedly transporting a woman across state lines for “immoral purposes”—city officials shut down his cafe.29 But other black-and-tan cabarets soon opened along State Street between 28th and 35th Streets.30 The Chicago Defender sometimes called them “cabray cafes,” probably reflecting how some people pronounced the word.31

“The typical black and tan accommodated fewer than 100 couples and hosted concert performances as well as floor shows of professional singers or dancers, whose entertainment and lyrics were often bawdy and designed to provoke audience reaction,” Vaillant wrote. “What chiefly distinguished the black and tans was the presence not only of African American performers but also of multiracial audiences, among whom could be found multi- and interracial couples.”32

It’s no surprise that racists were quick to condemn the mingling of white and Black patrons in the South Side’s black-and-tans, where “black folk and white met on something approaching the same social level,” as sociologist Walter C. Reckless put it in a 1933 book, Vice in Chicago. “To a slumming white patronage the Black Belt location of cabarets offered atmosphere and the colored man’s music and patronage added thrill. When the black-and-tan development was noticed, the newspaper reporters, in their characteristic way, described these black-and-tan places as ‘worse than the worst.’”33

The Chicago Commission on Race Relations criticized newspapers for using these black-and-tans as an excuse for “arousing sentiment against the mingling of races.” But even the commission (a panel of white and Black community leaders appointed in the wake of the 1919 Chicago race riot) found reason to criticize these South Side cabarets:

These resorts, with their liquor selling and coarse and vulgar dancing, are highly dangerous to morals and established law and order, and a nuisance to the neighborhoods in which they are located. They are used as amusement places, both by white couples living in other sections of the city and by Negro couples who live near them. … The habitues of these resorts are usually of an irresponsible type of pleasure seekers, and frequently they are vicious and immoral.34

In his 2003 book, Vaillant concedes that black-and-tan cabarets fell short of being “race-blind utopias,” but he argues that they created a space where Black and white people—and even same-sex couples—could come together to socialize, dance, and enjoy live music and other entertainment, without fear of censure or harassment.35

The Tribune offered a glimpse inside the Pekin, a black-and-tan cabaret where Tom Chamales had been a co-owner for a time. Written by someone using the mysterious nom-de-plume “Investigator K.,” the 1920 report was intended as an exposé of the club’s illegal practices of staying open late and selling liquor. And the writer may have intended to shock readers with details about white and Black people drinking and dancing together. But it’s hard not to wonder if K. was actually having some fun.

The story began: “Lawless liquor—sensuous ‘shimmy’—solicitous sirens—wrangling waiters—all the tints of the racial rainbow—black and tan and white—dancing, drinking, singing—early Sunday morning at the Pekin café, 2700 South State street.”

According to K., the crowd inside the Pekin included “the society man, the chorus girl, the gangster, the lawyer, the jazzbo—all heeding the call of the bright lights.” These folks ascended a stairway into the club after midnight, and by 1 a.m., the joint was crowded. The report continued:

A syncopating colored man had been vamping cotton field blues on the piano. A brown girl sang. “I’d take mos’ any kind of a chance,” she screamed. Then she shimmied. A dollar turned the “shimmy” into a muscle dance that put the old time “hootch” to shame. Two black boys moaned and screamed on saxophone and clarinet. …

Highballs were ordered. They came, fast and furious, the diluted remnants of good bourbon. The dance floor was now jammed. Dancing “across the table” was in vogue. A painted girl would “give the eye” to a man across the hall and then they hurried to the dance floor. Once there, they picked a spot and wiggled. One girl returning from the flood found her chiffon waist disarranged, and her hennaed hair was falling around her shoulders. …

All the tables were filled at 2 o’clock, black men with white girls, white men with yellow girls, old, young, all filled with the abandon brought about by illicit whisky and liquor music. The entrance was jammed. Passage out was a struggle. Outside on the sidewalk were many more couples. On the street were several limousines.36

Another early cabaret was Colosimo’s, which opened in 1913 at 2126-28 South Wabash Avenue.37 Its owner was “Big Jim” Colosimo, the boss of a criminal organization that would be taken over by Johnny Torrio in 1920—when Colosimo was gunned down at his restaurant, probably on Torrio’s orders. Al Capone later became the boss of the same mob.

Colosimo’s place was a classy Italian restaurant featuring “public dancing” and “refined cabaret.”38 At Colosimo’s, a big part of the attraction was to see who else was dining, drinking, and dancing there. Almost as soon as it opened, Colosimo’s became known as a popular late-night rendezvous for theatrical performers.

“The cafe is … crowded nightly after the show with a merry making throng which makes it one of the brightest spots on the city’s map,” the Inter Ocean reported in 1913. “Here may be seen some of the big stars of the profession—men and women whose names are seen constantly in electric lights along Broadway and Randolph street. At another table perhaps may be a group of pretty chorus girls, all mingling in the spirit of the place and forgetful for the time being of that vast social and professional chasm that is supposed to lie between the big spot lighter and the humble little spear carrier.”39

What sort of dancing was featured on the stages in Chicago cabarets? Chicago Daily News critic W.K. Hollander was reminded of local cabarets when he saw the scantily clad Russian actress Alla Nazimova dancing in the 1918 movie Revelation. “Bare legged and briefly garbed she cavorts about haphazardly, an irresponsible human, spreading good cheer and happiness such as one encountered in Chicago cafes and cabarets,” Hollander wrote.40

Those Chicagoans who were outspoken about the dangers of drinking and prostitution—the city’s reformers, puritans, and temperance and prohibition advocates—saw cabarets as a new form of temptation. “The cabaret emerged during the period of vice suppression in Chicago and other American cities,” Reckless wrote, describing how cabarets “emerged out of red-light backgrounds as a new type of pleasure about 1914.” Cabarets were seen as a replacement for other places shut down by authorities during the reformers’ drive to clean up Chicago in the early 1910s, such as the brothels in the South Side’s Levee.

“An increase of cabarets followed upon the breaking up of the segregated districts,” sociologist Harvey Warren Zorbaugh wrote in 1929. According to Zorbaugh, cabarets “largely took over the functions of the saloon and the house of prostitution.”

Although the sense of personal contact between entertainers and patrons in cabarets seemed like a new phenomenon, Reckless argued that it was just a new variation of regular activities inside the Levee’s saloons and brothels, where prostitutes solicited men sitting at tables. And so, it was natural that Chicago’s puritan crowd would view the new cabarets with suspicion. Reckless asserted that the two main features of cabarets, “saloon-café life and the public dance,” had an “intimate connection … with prostitution.” Zorbaugh believed that cabarets—and the intimacy they fostered—were part of “the gradual letting down of all sexual conventions.”41

Reckless concluded that prostitution and liquor weren’t the only reasons why cabarets boomed in popularity. It had more to do with changes in society, including “the emancipation of respectable persons (especially women) from the former inhibiting norms of conduct.” The lives and habits of people living in big cities like Chicago were changing. And these changes led to “radical developments in public behavior of pleasure seekers,” Reckless wrote. Cabarets didn’t cause these changes. They were simply places that answered people’s desires for a night of entertainment and socializing.42

According to the Juvenile Protective Association, cabarets rapidly began opening across the city around 1914. More than half of Chicago’s 7,000 saloons had a cabaret space by 1916, according to the group’s estimate.43 This may well have been an exaggeration: Two years later, city officials said Chicago had 230 establishments that functioned solely as cabarets, plus 1,070 saloons with backroom cabarets.44

The Juvenile Protective Association was especially worried about the “young girls” employed as entertainers at most of these joints. Louise DeKoven Bowen, a leader at the JPA who’d also worked at Jane Addams’s Hull House, wrote about the plight of these girls, in a 1916 pamphlet titled The Road to Destruction Made Easy in Chicago:

It is not required of these girls that they should sing well or be especially proficient in dancing. They are put in the cabarets in order that they may drink with the patrons and the girl who is most valuable is the one who is able to induce a customer to order the largest number of drinks. …

Many of the songs sung by the entertainers are obscene; in fact, when a girl applies to an agent for a position he asks her what songs she knows, and often remarks after hearing them that they are not “tough enough,” and urges her to think up something else, making it clear that he wishes to arouse the baser passions of the patrons. Kissing at the table is extremely common, men often crossing over to other tables and embracing women in the most open manner. At one cabaret the proprietor told a girl entertainer that he would give her and the other girl entertainers, rent free, rooms upstairs, and urged them to make “easy money.” …

One of the worst features of this rapid development of the cabarets is that the girl who becomes a professional entertainer faces three perils. First, she is interviewed by an agent—often disreputable—and although she may escape from his attentions, when she enters the cabaret she places herself in the power of the proprietor, who, in many cases, makes evil demands upon her. Lastly, she is an open prey for the disreputable patrons who, demoralized by drink, force their attentions upon her.

There are a vast number of young girls who find this occupation a new opportunity for earning money, and there are many other young women who would not dream of accepting an invitation from an escort to enter an ordinary saloon and to drink over the bar, who are willing to attend a so-called entertainment even though it be held in a room back of a saloon. Literally thousands of young people—young boys as well as girls—thus make their first acquaintance not only with public drinking, but with disreputable characters and become familiar with that sinister evil which apparently has a never-ending capacity for masquerading as recreation.45

Louise DeKoven Bowen. Photo: Bain News Service, Library of Congress.

It’s probably true that many girls and young women were being exploited. But Bowen failed to consider the possibility that some of them actually performed music and dances with artistic merit. “Bowen portrayed female cabaret singers as pliant instruments of amoral cabaret operators, who hired performances on the basis of their youth and attractiveness and urged them to sing ‘tough’—that is, bawdy—material,” Vaillant wrote.46

(Content warning: The next three paragraphs describe a suicide.)

When a 17-year-old cabaret singer named Sadie Snyder killed herself in Lincoln Park in 1916, her friends blamed the barrage of hurtful rhetoric about cabaret singers from groups such as the Juvenile Protective Association.

“She would read the stories in the paper about Chicago cabarets and then become moody,” Morris Evanson said. “She liked to sing, but refused several offers from cabarets which did not have good reputations. I tried to tell her that those stories were just hot air, but she said that many people who read them would believe everybody connected with the cabarets were bad. She was a good, straight girl. She wouldn’t work in the tough cafés. She had several offers. She had a fine voice and the proprietor of the Delavan Café told her she could sing there as long as she wanted to.”

Snyder’s mother found her body after she’d died from inhaling gas. A newspaper, folded to a story about the conduct of patrons in a Chicago café, was lying on the floor next to her bed. The words “Mama, I love you” were scribbled on the wall.47

Mad About Dancing

Meanwhile, Green Mill Gardens and the other cabarets and gardens were also providing Chicagoans with places to dance, at a time when America was in the midst of a dance craze. Reformers had long been suspicious of Chicago’s dance halls. When the Vice Commission issued its 1911 report The Social Evil in Chicago, it estimated that Chicago had 275 public dance halls, including many that were rented periodically to clubs and societies. The Vice Commission offered this summary of the evils perpetrated by dance halls:

Many of these halls are frequented by minors, both girls and boys, and in some instances they are surrounded by great temptations and dangers. Practically no effort is made by the managers to observe the laws regarding the sale of liquor to these minors. Nor is the provision of the ordinance relating to the presence of disreputable persons observed.

In nearly every hall visited, investigators have seen professional and semi-professional prostitutes. These girls and women openly made dates to go to nearby hotels or assignation rooms after the dance. In some instances they were accompanied by their cadets who were continually on the lookout for new victims. Young boys come to these dances for the express purpose of “picking up” young girls with whom they can take liberties in hotels, rooms or hallways of their homes.48

The Juvenile Protection Association investigated 328 dance halls, concluding that more than half of these places sold liquor to minors. “The grossest and most dangerous form of tough dancing was being practiced,” Bowen wrote. Dance hall employees “were always ready to give information to young people regarding the location of disreputable hotels, and in many cases the use of the dance hall premises for immoral purposes was connived at by the management,” she wrote. “Many of the halls were poorly lighted; there was little protection in case of fire and the ventilation was wretched.” 49

In those early years of the 20th century, ragtime had inspired new styles of dancing, but many people in the country’s growing middle class disdained vulgar dances like the “Grizzly Bear.” They wanted a new style of dancing that was modern but also acceptable in polite society.

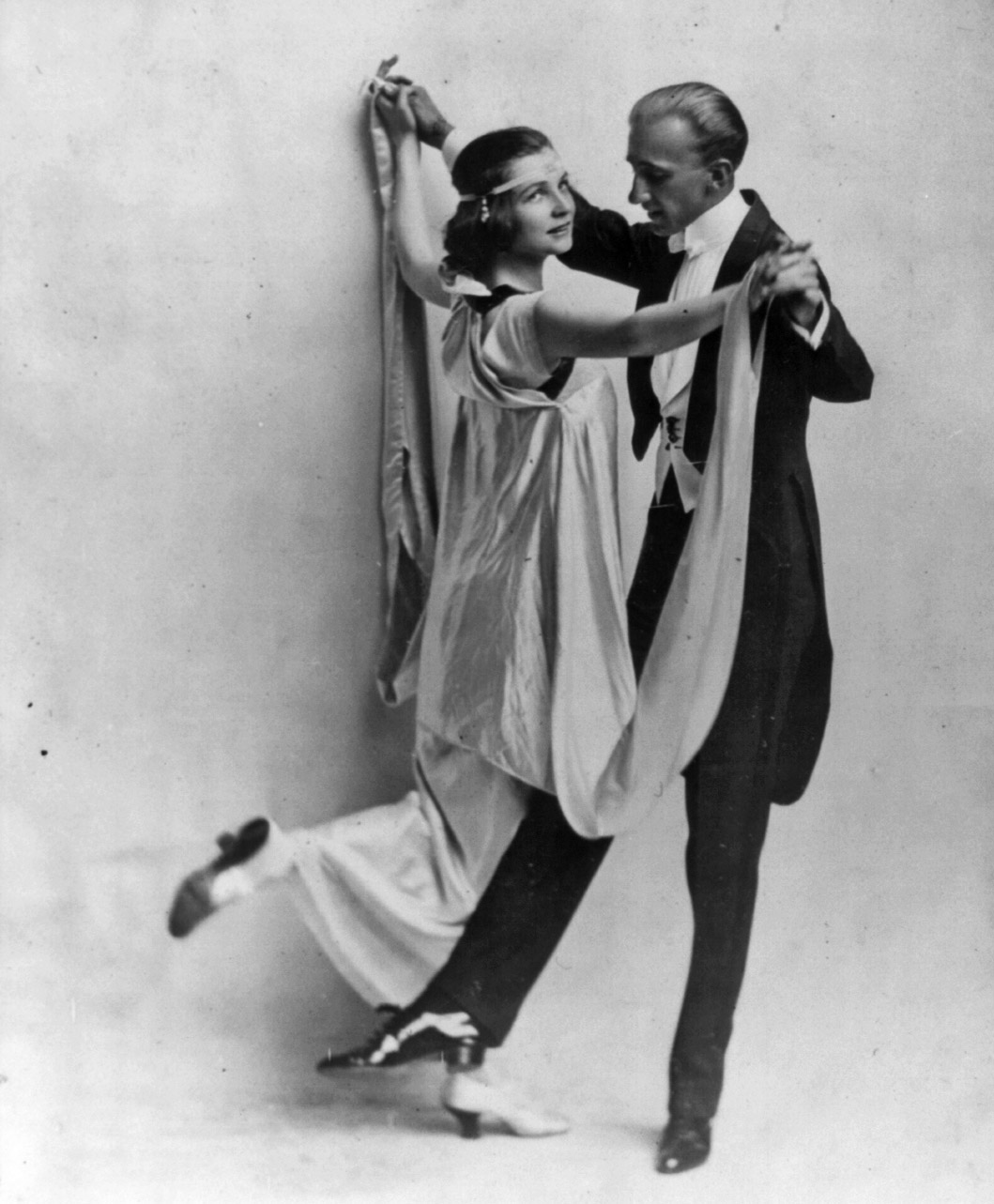

Vernon and Irene Castle took those ragtime influences and created dances that seemed more respectable. It was “a new form of ballroom dance—elegant, smooth and sophisticated,” Richard Duree wrote in Let’s Dance! magazine. “… Their new style of dance was perfect for Ragtime music and a perfect match with the expectations of the new America.” 50

Vernon and Irene Castle, photographed in 1914. Library of Congress.

The American couple first gained fame in Paris, before returning to New York in 1912 and becoming a sensation on Broadway. They popularized dances such as the foxtrot and opened a dance school in 1914,51 stopping in Chicago that year during a whirlwind tour,52 even as a movie of them dancing was shown in Chicago theaters.53

“Mr. and Mrs. Vernon Castle, dancers swinging ‘round the circle for the propaganda of modern dancing, will appear tomorrow afternoon and evening at Orchestra hall,” the Inter Ocean reported on May 3. “Their program will include their ‘Innovation Dance,’ devised to combat the objections to the tango; the ‘Hesitation,’ ‘Maxine,’ ‘Argentina Tango’ and their ‘Half and Half.’ They bring their own orchestra and Mr. Castle turns himself into an orator. A tournament for amateurs will be a part of the program.”54

The Talking Machine Shop (on the fourth floor of the Steger Building, at the northwest corner of Jackson Boulevard and Wabash Avenue, an area of the Loop known as Music Row) hosted an informal reception for the Castles on May 4, launching what the store called “Castle Week in Chicago.” As an ad explained, “Mr. and Mrs. Castle have done so much to elevate and to beautify the modern dance, and their Orchestra has recorded such perfect Dance Music upon Victor Records, that we all owe a deep debt to their art.”55 On the same day, Chicago’s Regal Shoe Company announced that it was the exclusive seller of dancing shoes designed and worn by the Castles. 56

“The Castles launched a dance craze that has not been equaled in this country before or since,” Duree wrote. “… It was democracy in dance and America wanted all it could get.”57

“Their elegance of motion and rhythm opened up a new world to an American public for whom dancing mostly had been a stiff, overly formal, and sometimes awkward social experience or a series of ritualistic ethnic folk dances,” Sengstock wrote in That Toddlin’ Town. “ … Maurice and Walton and other dance teams also appeared on Chicago stages and in cabarets about this time, further sparking interest in ballroom dancing. It became a social pastime open to everyone, not just high society. After that, dancing no longer was limited to traditional waltzes or the two-step. In Chicago several early dance halls were prospering in the pre-World War I period and many new cabarets joined the dancing party.”58

At the same time, movies were booming in popularity. Many restaurant owners began offering entertainment to compete with the movies, according to Chicago Daily News theater critic Amy Leslie. She described how it became impossible to enjoy a quiet meal as restaurants transformed into cabarets, where people ate amid “the wild orgies of the oboe, the fiercely pounded drum, wheezed tuba and untrammeled piano, not to mention the lurid shouter of the rag and added hundreds kicking dust into other people’s dinners while the mad fox trot unleashed the germ clouds from the floor.” While this noisy spectacle annoyed some folks, “there were those who adored the strenuousness of it,” Leslie wrote. “… They would come miles and spend the price of a marriage license for the exultant gluttony of the rapturous cabaret.” 59

When Green Mill Gardens opened in June 1914, cabaret culture—already flourishing on Chicago’s South Side—was firmly established on the North Side. And crowds of young people arrived, eager to foxtrot the night away.

A Mission Statement

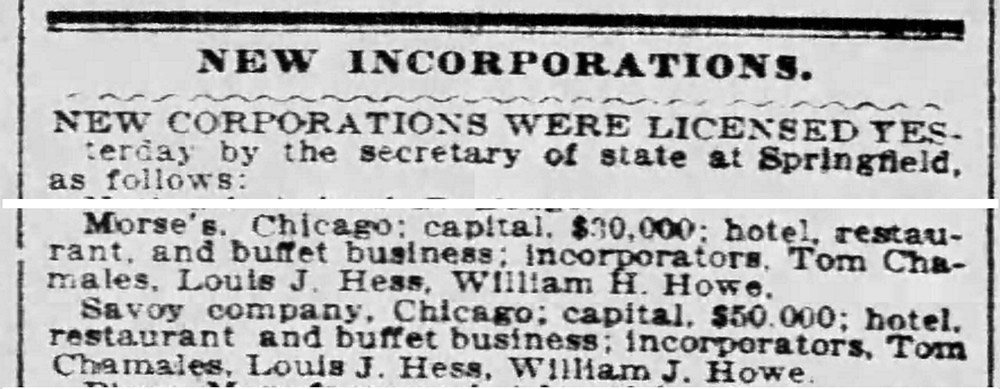

Tom Chamales had filed paperwork with the Illinois secretary of state’s office to form a corporation eight months after he started leasing the saloon formerly known as Pop Morse’s roadhouse. He used that name for his corporation, giving it a simple, one-word name: Morse’s. In 1916, this corporation would change its name to Green Mill Gardens Inc., but for the time being, Chamales was still using the saloon’s old name.

Chamales had big plans for the roadhouse he was leasing at the northwest corner of Evanston Avenue (now Broadway) and Lawrence Avenue. The corporation papers filed on May 24, 1911, reveal an ambitious plan to create a sort of food, drink, and entertainment empire. Here is the text of his new company’s official mission statement:

The object … is to maintain and operate coffee houses, restaurants, eating houses, taverns, buffets, or other places of enjoyment and refreshment.

To carry on the business of hotels; restaurants; coffee houses; beer houses; refreshment rooms; and lodging house keeper; licensed victualler; wine, beer and spirit merchant; brewer; malster; distiller; importer and manufacturer of aerated waters and artesian water and other drinks; purveyor and caterer for public amusements generally; coach, cab and automobile proprietor; livery and garage keeper; farmer; dairyman; ice merchant; importer and broker of food, live and dead stock and domestic and foreign products of all descriptions; hair dressing; perfumer; chemist; proprietor of clubs, baths, dressing rooms; laundries; reading, writing and newspaper rooms; maintaining and operating roof gardens and other places of amusement, recreation, sport of entertainment; agents for railroads and shipping companies and carriers, theatrical and opera box proprietors; and any other business which can be conveniently carried on in connection therewith.

To carry on the business of theatrical and music hall proprietors, concerts and public exhibitions, vaudeville and variety entertainments; and to provide, engage and employ actors, dancers, singers, athletes, musicians, artists and variety performers; and to produce and present to the public all sorts of shows, exhibitions and amusements which are or may be produced at a theater or music hall; to acquire copyrights, rights of representation, licenses and privileges of any sort likely to be conducive to the benefit of the company; and to employ persons to write plays, songs and music and to compose or invent dances; and to print and publish plays, poems or songs of which the company may have the copyright, or the right to publish.

To own, acquire, maintain, carry on and conduct the business of wholesale and retail cigar and tobacco dealers.

To manufacture, buy, sell, import and export, to distill and brew, spirits, liquors, beers, wines or liquids of any kind; to brew, bottle, buy and sell all kinds of ale, beer, porter and other beverages; and to deal in malt and hops and products thereof; to acquire, lease, mortgage and sell licenses for the sale of any such beverages.

To do a general merchandising and mercantiling business.

Two other men signed the corporation papers along with Chamales: Louis J. Hess, a saloonkeeper-turned reporter,60 and William H. Howe. But as the company got started, Hess and Howe were not among the officers or shareholders. Morse’s had $30,000 in capital stock. Chamales owned 298 of the company’s 300 shares, or $29,800. His brother William Chamales and Peter Malakates each had one $100 share. It’s clear who was running the show: Tom Chamales.

At the same time, Chamales filed paperwork to start another corporation, called Savoy Company—based at his downtown saloon, the Cafe Savoy at 600–602 South Wabash Avenue. Word for word, the Savoy Company had the exact same mission statement as Morse’s. But it had even more capital stock: $50,000. Tom Chamales owned 498 shares valued at $49,800, while Hess and his brother William each had a single $100 share. The Savoy Company had a sublease at the Wabash Avenue location for 15 years and 10 months starting on June 1, 1911.61

Chamales clearly intended to continue running the Savoy for many years to come, but that isn’t what happened. It stayed in business for a few years, but it was no longer listed in city directories after 1916. Chamales put it up for sale in a 1917 classified ad.62

He seemed to be focused on running his other business, up on the North Side.

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER—>

Footnotes

1 “‘Protect Women From Thugs,’ Cry of Aroused Citizens, Who Will Hold ‘Safety Meeting,’” Chicago Examiner, June 11, 1911, 3.

2 “Evanston Avenue Becomes Broadway With Midnight,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 15, 1913; “Eliminating Duplicate and Meaningless Street Names and Principle of Substitution,” Chicago Commerce, September 5, 1913, 33, https://books.google.com/books?id=VQerfUMv9v0C&pg=RA19-PA33; “George Rogers Clark and Clark Street,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 1, 1927, 10.

3 Document 7048590, Book 16543, 500-510, lease agreement between Catherine Hoffman and Tom Chamales, February 28, 1913, recorded January 28, 1921, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division, 507.

4 “Chicago Vaudeville,” New York Clipper, March 21, 1914, . https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19140321.2.172&srpos=2&e=——-en-20–1-byDA-img-txIN-%22pop+morse%22———

5 “U.S. Ban Makes City Dry in Fact as Well as Name,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 1, 1919, 17.

6 “The Moulin Rouge,” Grand Island (NE) Daily Independent, November 6, 1889, 2. Reprinted from London Standard.

7 Theodore Child, “Mlle. Yvette Guilbert,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 17, 1891, 9.

8 “Amusements,” Inter Ocean, June 7, 1892, 4.

9 “Can-can,” Wikipedia, accessed June 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Can-can.

10 Lucy Sante (as Luc Sante), The Other Paris (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 170.

11 Maurice Boukay, words, and Marcel Legay, music, Chansons Rouges (Paris: Ernest Flammarion, 1896), 51-56, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.c034420439?urlappend=%3Bseq=11%3Bownerid=13510798903885961-15.

12 “At the Moulin Rouge,” Inter Ocean, December 9, 1900, 3. Reprinted from (London) Pall Mall Gazette.

13 “America 1900: Summing Up, Looking Forward and the Paris Exposition,” PBS, accessed May 22, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/1900-forward-exposition/.

14 “Rains Help Paris Fair,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 5, 1900, 10.

15 Burns Mantle, “‘All ‘Round Chicago’—(?),” Inter Ocean, May 2, 1905, 6.

16 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 13, 1899.

17 “Plan a War on Resorts,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 5, 1899; “To Fight Beer Gardens,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1899, 10.

18 “Summer Gardens & Picnic Groves,” Jazz Age Chicago, accessed May 23, 2023, https://jazzagechicago.wordpress.com/summer-gardens-picnic-groves/; “The Many Lives of the Marigold Gardens, Steps From 3750,” 3750 Lake Shore Drive, Inc., December 28, 2022, https://www.3750lsd.net/the-many-lives-of-the-marigold-gardens-steps-from-3750/.

19 “History of Ravinia,” Ravinia Festival, accessed June 8, 2023, https://www.ravinia.org/History.

20 Paul Kruty, “Pleasure Garden on the Midway,” Chicago History, fall-winter 1987-88, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 14, 15.

21 Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, They All Played Ragtime (New York: Oak Publications, 1971), 149-150.

22 Perry R. Duis, The Saloon: Public Drinking in Chicago and Boston, 1880–1920 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 253; Jean Cowgill, “Finds Evil in Dance,” Chicago Chronicle, January 3, 1904.

23 Raymond Calkins, Substitutes for the Saloon, 2nd ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1919), 13.

24 Duis, Saloon, 253; “Fight for Saloon Music,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 11, 1903.

25 Katherine Anne Yachinich, “The Culture and Music of American Cabaret,” music honors thesis, Trinity University, May 2014, 4, https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=music_honors.

26 Yachinich, 3.

27 Derek Vaillant, Sounds of Reform: Progressivism and Music in Chicago, 1873-1935 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 203.

28 Yachinich, 25.

29 Charles J. Johnson, “The Short, Sad story of Cafe de Champion — Jack Johnson’s Mixed-Race Nightclub on Chicago’s South Side,” Chicago Tribune, May 25, 2018, https://www.chicagotribune.com/history/ct-met-cafe-de-champion-jack-johnson-chicago-20180525-story.html.

30 Yachinich, 24.

31 Columbus Bragg, “On and Off the Stroll,” Chicago Defender, August 15, 1914, 6.

32 Vaillant, Sounds of Reform, 208.

33 Walter C. Reckless, Vice in Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1933), 102-103, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ien.35559000622799.

34 The Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1922), 323, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t6058439j?urlappend=%3Bseq=459.

35 Vaillant, Sounds of Reform, 208; Yachinich, 23.

36 “‘Lid’ a Joke as Pekin Shimmies Defiance of Law,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 16, 1920, 17.

37 Chicago city directories, 1911–1917, Fold3.com; “Colosimo,” My Al Capone Museum, accessed June 4, 2023, https://www.myalcaponemuseum.com/id50.htm; “Big Jim Colosimo—Chicago’s first crime boss,” Chicago Tribune, May 29, 2020, https://www.chicagotribune.com/visuals/vintage/ct-chicago-gangster-big-jim-colosimo-photos-20200529-76s4zup6pzdkvazl3hwwwidxlq-photogallery.html.

38 John J. Binder, Al Capone’s Beer Wars: A Complete History of Organized Crime in Chicago During Prohibition (New York: Prometheus, 2017), 52, 60-61.

39 “Colosimo’s Restaurant Is Rendezvous of Late Diners,” Inter Ocean, December 21, 1913, magazine, 6.

40 W.K. Hollander, “Nazimova Is at Best in ‘Revelation’ Film,” Chicago Daily News, May 15, 1918, 14.

41 Vaillant, Sounds of Reform, 100, 118; Harvey Warren Zorbaugh, The Gold Coast and the Slum: A Sociological Study of Chicago’s Near North Side (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1929), 120n1.

42 Reckless, Vice in Chicago, 118.

43 Louise DeKoven Bowen, The Road to Destruction Made Easy in Chicago (Chicago: Juvenile Protective Association of Chicago, 1916), 12, 14, https://books.google.com/books?id=E5Ll7wAtwzcC.

44 “Wets to Curb Cabarets and Protect Bars,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1918, 1-8.

45 Bowen, Road to Destruction, 12, 14, 15.

46 Vaillant, Sounds of Reform, 207.

47 “Cabaret Singer Ends Her Life by Gas in Room,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 17, 1916, 5.

48 The Vice Commission of Chicago, The Social Evil in Chicago: A Study of Existing Conditions (Chicago: Gunthrop-Warren Printing, 1911), 185, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b5188483?urlappend=%3Bseq=199%3Bownerid=102781651-217.

49 Bowen, Road to Destruction, 9.

50 Richard Duree, “The Dance Is Us,” Let’s Dance!, April 2014, 11-12, http://www.folkdance.com/LDArchive/2014April.pdf.

51 “Vernon and Irene Castle,” Wikipedia, accessed June 8, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vernon_and_Irene_Castle.

52 Charles A. Sengstock, That Toddlin’ Town: Chicago’s White Dance Bands and Orchestras, 1900–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2004), 2.

53 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, April 14, 1914, 13.

54 “‘Round the Theaters,” Inter Ocean, May 3, 1914, magazine, 7.

55 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, May 4, 1914, 8.

56 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, May 4, 1914, 9.

57 Richard Duree, “The Dance Is Us,” Let’s Dance!, April 2014, 12, http://www.folkdance.com/LDArchive/2014April.pdf.

58 Sengstock, That Toddlin’ Town, 2-3.

59 Amy Leslie, “Tearful Obsequies of Cafe Cabarets,” Chicago Daily News, May 11, 1918, 10.

60 Chicago city directories, 1906–1911.

61 Proposals to form corporations, May 24, 1911; books of subscription, May 26, 1911, Morse’s and Savoy Company, corporation papers, Secretary of State (Corporations Division): Dissolved Domestic Corporation Charters, 103/112, Illinois State Archives, Springfield; “New Incorporations,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 28, 1911, 6.

62 Classified advertisement, Chicago Daily News, May 19, 1917, 25.