Chapter 1 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— INTRODUCTION / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER (coming soon) —>

The Green Mill did not open in 1907. Maybe you’ve heard that it did. Many articles say 1907 was the original founding date for this legendary jazz club in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood. This supposed fact gets repeated over and over again. But it’s simply not true.

As I’m writing this—in March 2023—the current version of Wikipedia’s entry about the Green Mill says this: “Originally named Pop Morse’s Roadhouse, the business opened in 1907.”

Nope. Wrong.

As I’ve learned from my research—combing through many old newspaper articles, court documents, and property records—the Green Mill’s actual history doesn’t always match up with the stories you may have heard about its early days.

So, when did it open? That depends on how we define “open.”

If we’re talking about when the Green Mill began operating as a bar in the space where it is today—and has continued operating ever since—that seems to be 1935. That’s when the bar at 4802 North Broadway was listed for the first time in Chicago telephone books, opening two years after a large fire caused extensive damage to the building. It was also two years after the end of Prohibition, so it was the first time since 1919 that liquor was sold at this location (legally, anyway).

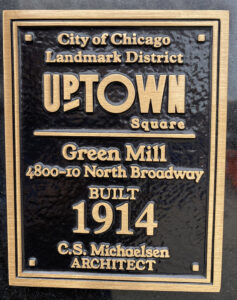

But there are other ways to define the Green Mill’s opening date. When was the first time an establishment called the Green Mill operated at the spot where the jazz club is today? That was June 1914, when the much larger Green Mill Gardens opened at the northwest corner of Broadway and Lawrence Avenue. A few years ago, a plaque was placed on the Green Mill’s exterior, noting that it was built in 1914. As more people notice this plaque, that might help to establish 1914 as the year people think of as the Green Mill’s origin.

But there are other ways to define the Green Mill’s opening date. When was the first time an establishment called the Green Mill operated at the spot where the jazz club is today? That was June 1914, when the much larger Green Mill Gardens opened at the northwest corner of Broadway and Lawrence Avenue. A few years ago, a plaque was placed on the Green Mill’s exterior, noting that it was built in 1914. As more people notice this plaque, that might help to establish 1914 as the year people think of as the Green Mill’s origin.

If you went back in a time machine to 1914 and stepped into the space where the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge is now, it’s unclear exactly what you’d see. It probably wouldn’t resemble the interior that you see today. But that this ground-floor space near the corner of Broadway and Lawrence was part of the overall Green Mill Gardens complex.

However, there’s a complicating factor if we use 1914 as the year when the Green Mill began: During the Prohibition Era, the place apparently shut down for some stretches of times—and at other times, it operated under different names, including the Montmartre Café and the Lincoln Tavern Town Club. So, it hasn’t been continuously open as the Green Mill (or Green Mill Gardens) since 1914.

We could also define the Green Mill’s founding date as the time when the first saloon opened at this location. That saloon wasn’t called the Green Mill, however. It was known as Pop Morse’s roadhouse. And it was demolished to make room for Green Mill Gardens. So, it’s debatable whether it qualifies as the first chapter of the Green Mill’s existence. Was it merely another business that existed at the same location before Green Mill Gardens opened? Or was it a business that evolved into the Green Mill?

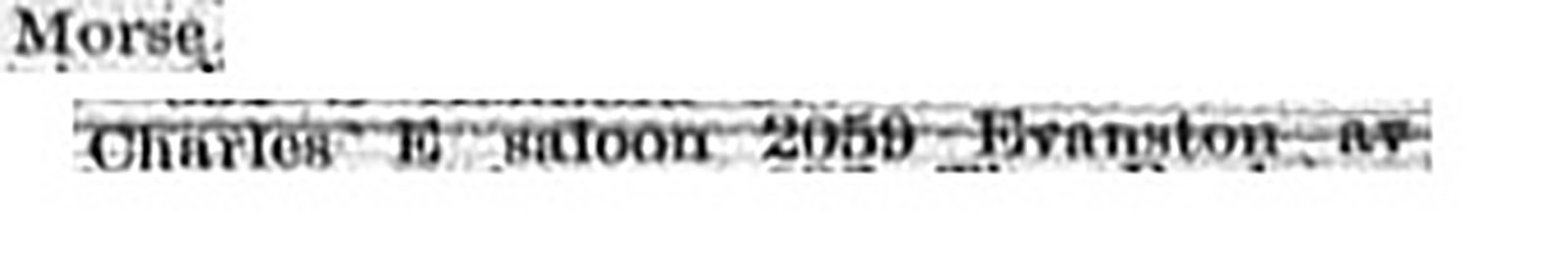

In any case, Pop Morse’s roadhouse did not open in 1907. The building permit for it was issued in the spring of 1897, and the saloon may well have opened later that year. It appeared in a city directory for the first time in 1898, and was mentioned in newspaper articles as early as 1899. (At the time, the building’s address was 2059 Evanston Avenue. That number changed to 4800 when Chicago’s street addresses were systematically reorganized in 1909; Evanston Avenue was renamed Broadway in 1913.1)

And so, depending on how we define the founding date, the Green Mill started in 1897 … or 1914 … or 1935.

Even if we think of Pop Morse’s roadhouse as a forerunner of the Green Mill—a prelude to the actual history—it’s a good place to begin the story.

Who was Pop Morse?

When Pop Morse died in 1908, he was something of a Chicago celebrity. According to the Chicago Daily Tribune’s obituary, nearly everyone in the city had heard of him. “Not to have known or heard of him stamps one as a newcomer in Chicago,” the newspaper wrote. 2

Charles Edward Morse was born in Massachusetts in 1847.3 A state census record from 1855 seems to be match for Morse, showing him as a boy in the city of Northampton, where his father tied brooms for a living.4

After serving in a Massachusetts regiment during the Civil War, when he was still a teenager, Morse came to Chicago and started working in a pop factory. According to his Tribune obituary, people started calling him “Pop” when he drove a wagon delivering soft drinks. “He did not remain at this occupation long, but long enough to give him his nom de guerre,” the Tribune explained.

And although his surname was Morse, many people called him “Pop Mose.” Perhaps that misspelling derived from the way his name was pronounced, or maybe it was a joke of some sort. “‘Pop Mose’ was not his name, but that was the appellation by which everybody knew him,” the Tribune wrote in 1908. “… Few of the hundreds who came to know him in recent years ever knew but that ‘Pop Mose’ was his real name.” The “Mose” misspelling was so prevalent that the Tribune used it in its obituary headline.5

According to that obit, Morse became a saloonkeeper sometime around the late 1860s. There were a few people named Charles Morse living in Chicago in 1870, but I haven’t found this particular Charles E. Morse in the U.S. census from that year. (Did the census enumerators overlook him or misidentify him? Or was the Tribune obituary incorrect about when he arrived in Chicago?) I also haven’t found any definite matches with Charles E. Morse in city directories before 1874. That’s the year when the city directory listed Morse’s residence at 285 Clark Street, where he ran a saloon with a partner, Archibald Donaldson.6

Assuming this was South Clark Street, that address became 405 South Clark Street after 1911. That’s the same block where the Metropolitan Correctional Center, downtown’s federal jail, stands today, across the street from some buildings that have survived since the 19th century. When Morse served booze there in the 1870s, the area was nicknamed “Little Cheyenne.” It was one of Chicago’s most prominent red-light districts, notorious for its brothels and saloons.7 The same block later included legendary alderman Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna’s tavern, the Workingmen’s Exchange,8 and it was Chicago’s original Chinatown.9 The street still has a row of old buildings (seen above in a photo I took in 2019), which Preservation Chicago included on a 2016 list of endangered historic properties.10

Morse married Annie Buckley, a New York native who was six years younger than him,11 and they had a son named Edwin (or Edward or Edmond) on June 5, 1879.12 Over the course of their marriage, Annie Morse would give birth to 10 children, but eight of them died when they were young. Ed was one of only two children in the family who survived long enough to reach adulthood.13

Within a year after Ed’s birth, Pop and Annie headed west from Chicago with their infant son, moving to Carbonateville,14 a mining town that had just sprung up when hard-rock silver was found in Colorado’s Ten Mile Canyon, near Leadville.

“Carbonateville had burst into being in 1878 on a plateau at the mouth of gold-rich McNulty Gulch,” historian Mary Ellen Gilliland wrote. “Carbonateville exploded, quickly gaining 61 businesses, including six hotels, four grocers, seven saloons, two sawmills — and one bank.”15 The picture above (from the 1916 book Olden Times in Colorado by Carlyle Channing Davis) is a “Sketch of the Early Leadville, Before Honored With a Name.” One of the Morse family’s new neighbors in Carbonateville took down their details for the U.S. census on June 5, 1880, describing 32-year-old Charles as a “merchant.”16 Morse opened a saloon, working in partnership with a man he’d met in the mining town.

This was when Morse experienced “one of the most exciting episodes” in his life, according to his Tribune obituary. Morse reportedly tried to stop a mob from lynching his business partner, who was accused of robbing a miner. Here is how the obituary recounted the episode:

One day a committee of vigilantes swooped down on the saloon. … The leader of the mob informed “Pop Mose’s” partner in a “few well chosen words” that they had come to lynch him. … Morse’s partner, who was serving drinks to thirsty miners, had no chance to escape.

“He’s my pardner, gentlemen,” spoke up Morse in defense of the trembling man at his side behind the bar. “If he’s robbed anybody he ought to suffer the consequences. But I’ll say to you, gentlemen, that I never heard of him doing anything very bad. I knew he’d like, but I didn’t think he’d steal. On my honor, gentlemen, I never suspicioned him as a thief.”

“Pop’s” partner was taken from the saloon and hanged to a tree near by. After the vigilantes had left, “Pop” went out and cut the body down. He then buried the corpse under the tree, being the only mourner. 17

It’s hard to say how accurate this story is. The Chicago newspaper reported it almost four decades after it reportedly happened in Colorado, without attributing the tale to anyone. Nor did the article give the name of the man who was lynched. Where did the Tribune reporter hear this story? It’s a fair guess that Morse had been telling the tale over the years. The Tribune treated it as one of the most important episodes from his life.

It’s true that vigilante mobs terrorized Carbonateville during the time when the Morse family lived there, according to The Carbonate Camp Called Leadville, a 1951 book by Don L. Griswold and Jean Harvey Griswold. The book describes an incident in which two men were lynched. One of the hanged men had a note on his back, signed by the “Vigilantes’ Committee.” The message added: “We are 700 strong.”18 According to local legend, four hundred “undesirables” left the area within 24 hours after those lynchings.19

Searching the Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection, I haven’t found any articles describing the lynching of Morse’s business partner, but there are many reports about crimes in the vicinity. In May 1880, the Colorado Weekly Chieftain commented: “Crime is rampant in the land, and Leadville is overstocked with it.”20 An 1881 story in the Leadville Weekly Herald mentions “Morse’s saloon,” which might be Pop’s place: “Just after the shooting the wounded man was conveyed to Morse’s saloon, and physicians were sent for, who immediately declared that the wound was moral, and the victim had only a few hours to live.”21

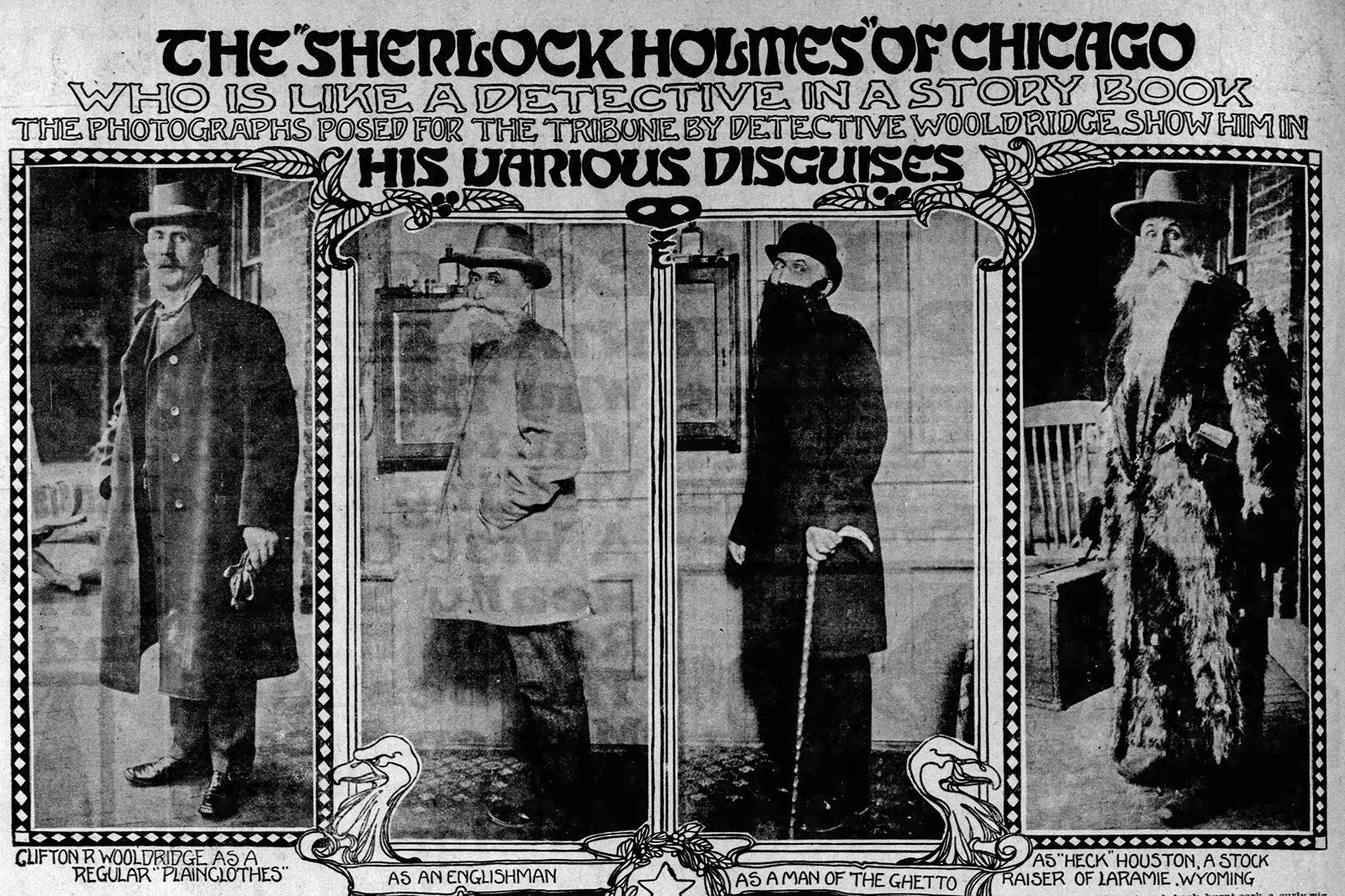

The 1908 Tribune story identified one member of the lynch mob that allegedly killed Morse’s business partner: Clifton Wooldridge, who later moved to Chicago and became one of the city’s most famous police detectives, ballyhooed as “the Sherlock Holmes of Chicago.”22 (Commenting on Wooldridge’s supposedly cunning disguises, Ricky Jay wrote: “To my somewhat skeptical, albeit untrained eye, the only distinguishing characteristics of these undercover identities is the length and style of facial hair.”23)

It’s unknown whether Wooldridge truly was a member of that lynch mob, but a book written by the detective includes biographical information placing him in the correct vicinity. Around 1879 or 1880, Wooldridge was working on the construction of a railroad in Leadville, Colorado.24

The Morse family returned to Chicago,25 where Charles and Annie’s daughter, Catherine (“Katie”), was born on January 12, 1883. She was the only child other than Ed who would make it to adulthood.26

From 1885 through 1889, Morse ran a saloon at 157 Third Avenue.27 That address is now 731 South Plymouth Court, in downtown’s Printers Row neighborhood. It’s just two blocks east of Federal Street—another street that was infamous as a red-light district in the late 19th century, when it was known as Fourth Avenue or Custom House Place.28

One night in January 1888, Morse went into “a house of ill-fame” at 130 Fourth Avenue (known today as 626 South Federal Street). According to a story in the Tribune, Morse got into a quarrel with a woman named Lilly and threw a spittoon at her, striking her in the neck. “Four or five men in the house then gave him a sound thrashing and threw him out of the door,” the Tribune reported.

Morse returned a few minutes later, bringing several friends with him. “They went through the house smashing the furniture and breaking things generally,” the Tribune reported. “In a back room they found hidden the four men who had assaulted Morse. A free fight ensued, during which half a dozen shots were fired.”

A bullet hit one of the men who’d attacked Morse earlier, Harry Robinson, in the thigh. The Tribune described Robinson as “a tough young ‘rounder,’ well known on the Levee, who is reputed to be worth nearly $100,000.” (Adjusted for inflation, that would be more than $3 million today.) Robinson wasn’t seriously wounded, and the newspaper noted: “It is not known who fired the shot and no arrests have been made.”29 We can only guess how Morse’s wife, Annie, reacted to her husband’s exploits.

Morse sometimes made news for less dramatic reasons. On at least two occasions, he was arrested and charged with allowing his saloon to stay open after the legal closing time of midnight—a rather run-of-the-mill offense during that era.30

Morse buys the Green Mill’s future site

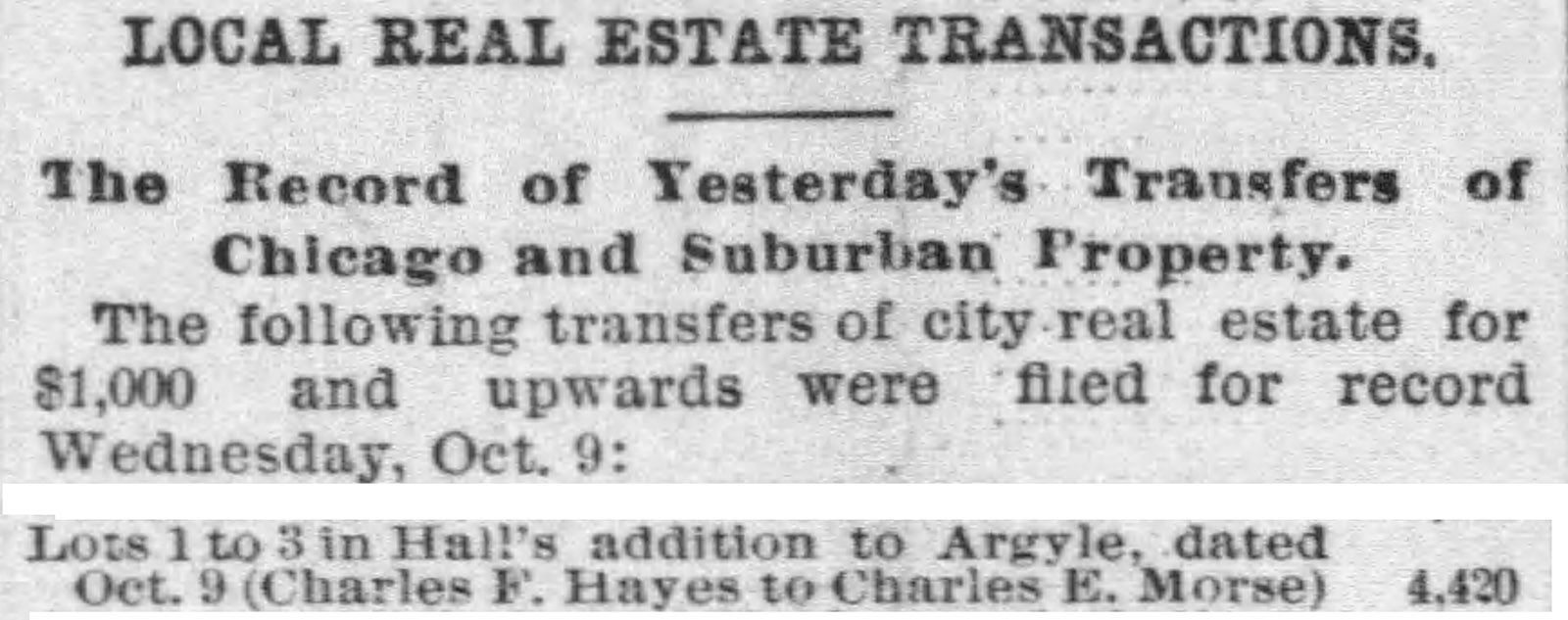

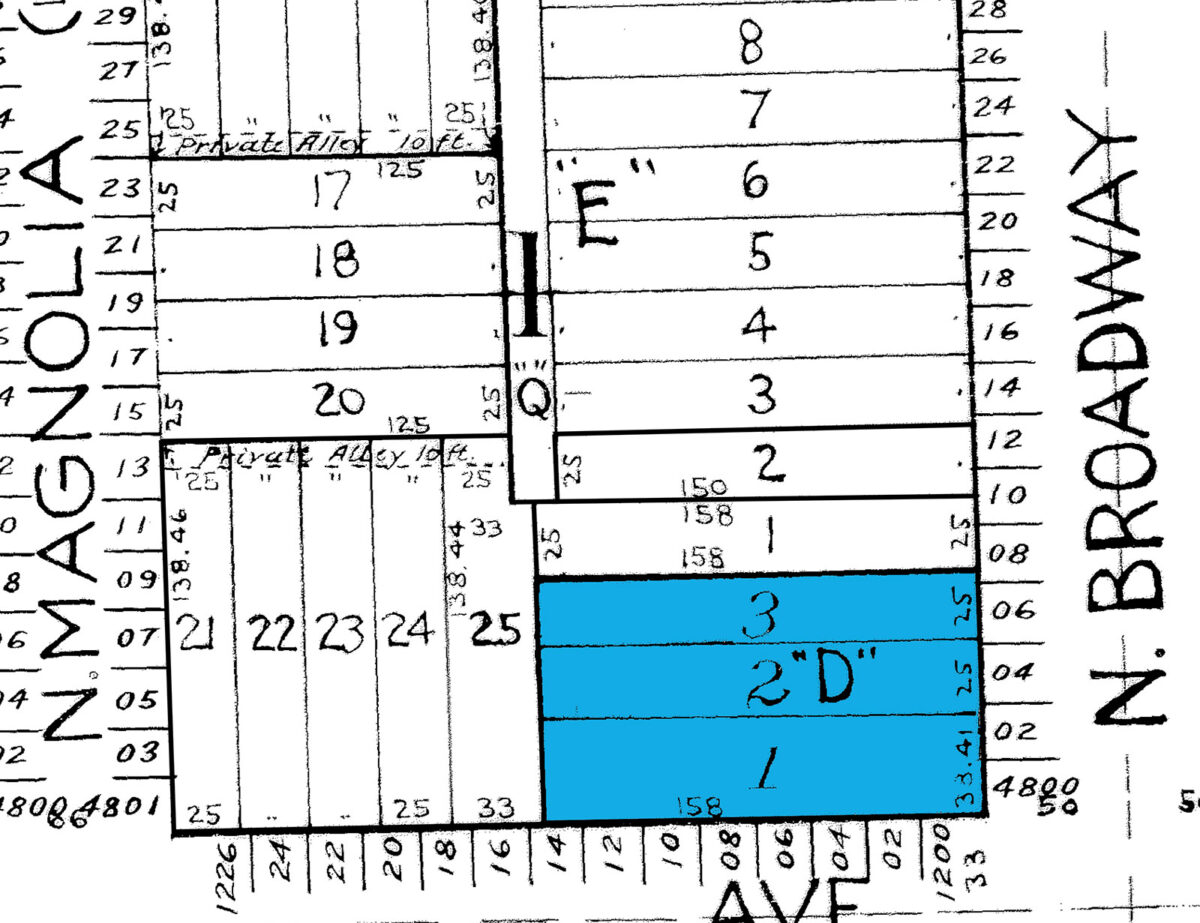

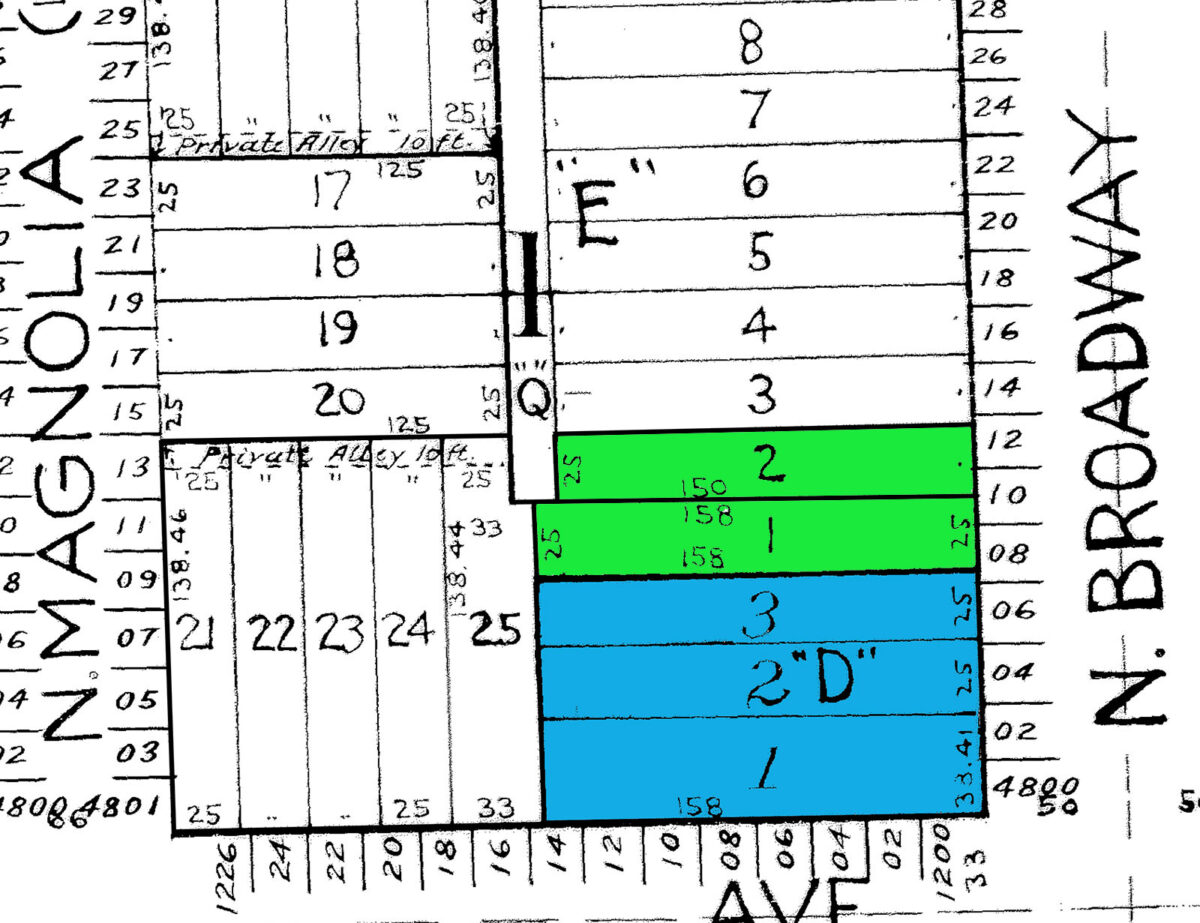

While he continued running saloons near downtown, Morse turned his attention to a more remote part of Chicago. On October 8, 1889, he purchased three vacant lots at the northwest corner of Lawrence and Evanston Avenues from Charles F. Hayes for $4,42031 (roughly $150,000 in today’s dollars).

This was the future site of the Green Mill, but at the time it was in sparsely inhabited area on the city’s outskirts. The land (known in Cook County’s property records as Rufus C. Hall’s Addition to Argyle) had been subdivided in October 1888, when it was still part of the City of Lake View.32

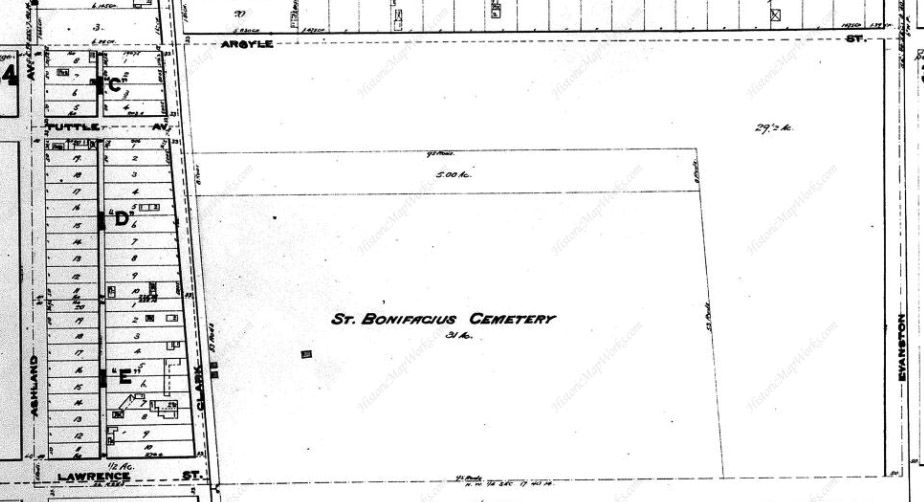

A year before that, the land had been part of a 29-acre, L-shaped property to the east and north of St. Boniface Cemetery, as seen on an 1887 map. 33

On July 15, 1889, Chicago annexed Lake View, so it was now part of the big city—but it was still more rural than urban.34

Six and a half miles north of the city’s center, Morse’s new property was in a region that was “little known by the average Chicagoan” at that time, according to the Inter Ocean newspaper.35

The land surrounding Morse’s property was largely vacant. In June 1890, some local residents suggested using it for the World’s Columbian Exposition if the fair’s planned site in Jackson Park didn’t work out. They proposed holding the fair on a 600-acre swath of land along the lakefront running from present-day Montrose Avenue up to Foster Avenue and stretching as far west as Clark Street. “There are no improvements to speak of on the lots,” the Tribune noted.36 (Of course, this plan did not come to fruition; the 1893 world’s fair was on the South Side.)

In 1894, most of the land around Morse’s property appeared as blank space in a fire insurance atlas published by the Sanborn-Perris Map Company. The neighborhood wasn’t known yet as Uptown—that name wouldn’t come into parlance until around 1920. The atlas shows other neighborhood names: The area along Wilson Avenue west of Clark Street was called Ravenswood. North of that were Bowmanville and Summerdale. Argyle was the name for the enclave around Argyle Street. And Buena Park was clustered around Evanston Avenue south of Montrose Avenue.37

Graceland Cemetery had owned land from Montrose up to Lawrence Avenue. But instead of serving as an extension of the graveyard, that land was developed starting in 1891 as the Sheridan Drive Subdivision, which came to be known as Sheridan Park.38

Why did Morse buy land out in this rural part of Chicago? Perhaps he had the foresight to realize the intersection of Evanston and Lawrence Avenues would boom in the years ahead. Or maybe he knew that roadhouses and so-called cemetery saloons were doing good business along Clark Street, serving mourners when they buried their loved ones or visited graves at Graceland Cemetery, St. Boniface Catholic Cemetery, and other nearby graveyards. Did he see the potential for a similar business along Evanston Avenue?

Morse did not build right away on his land. From 1891 to 1896, he ran a saloon down on the other end of Chicago—at 233 22nd Street (now 33 West Cermak Road), in the heart of the notorious Levee district—while he lived with his family on the South Side.39

Meanwhile, new transportation links opened in the early 1890s, making it easier to reach Morse’s property up in Lake View. The Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad added a station at Wilson Avenue.40 And the Chicago and Evanston Street Railway began operating trolleys on Evanston Avenue.41

Researching property records

One of the places I’ve gone to research this history is a room in the Cook County Building’s basement, where the shelves are filled with tract books listing all of the recorded transactions for each property in Cook County, starting after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 (which destroyed earlier documents) and going up through the 1980s (when the system switched over to computers). This used to be the Cook County recorder of deeds, but in 2020 it became part of the Cook County clerk’s office—a department called the recordings division.

It’s a treasure trove of information, but getting a look at all of those documents is a cumbersome and time-consuming process. (It will also get expensive if you want copies.) I haven’t had a chance to examine every single document related to the properties where Green Mill Gardens was—there are hundreds! But I looked over the tract books, as well as a handful of documents that were digitized, making them accessible on the computers in this basement office. (The other documents are on microfilm at a warehouse, but they can be requested for viewing.)

That was enough to get a basic picture of what happened with these properties, but many details are yet to be discovered. For example, it’s interesting to note that the Morse family took out six trust deeds on their land between 1889 and 1906. These are loans, similar to mortgages. The deed for the property is held in trust until the loan is paid off. Without seeing all of the documents, it’s unknown exactly how much the Morses borrowed. It appears that they paid off at least four of these six loans by the time Charles Morse died in 1908.42

The roadhouse opens

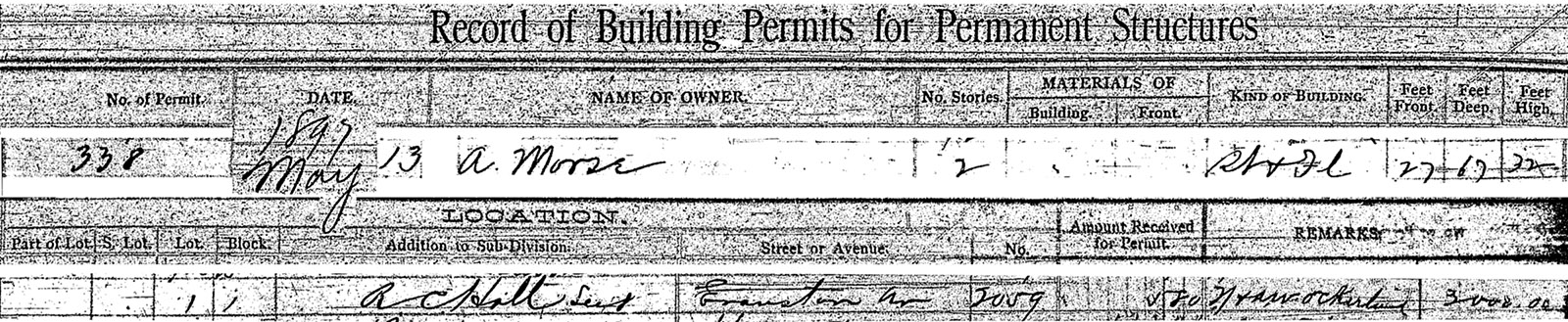

Morse finally started work on his new land in 1897. On May 13, the city issued a building permit for a two-story frame building containing a store and residential flats at 2059 Evanston Avenue. The permit allowed for a building 27 feet wide, 67 feet deep, and 32 feet high.43 The Morses hired J. Speyer & Son, of 164 La Salle Street, to build it for $3,500.44

Interestingly, the name of the property owner on the city’s building permits ledger is “A. Morse.” Did Annie Morse fill out the paperwork? Two of the trust deeds on the property were loans to “Annie Morse & husband,” suggesting that she took an active role in the family’s business affairs.45

The structure later appeared on a 1905 Sanborn fire insurance map: a restaurant-saloon at the intersection’s northwest corner, with a hitching shed just west of it along Lawrence Avenue. The diagram shows a small structure atop the second floor, perhaps a cupola or tower.46 (I haven’t found any photos or illustrations of the roadhouse, or any pictures of Pop Morse himself.)

The Chicago city directory for 1898 listed Charles E. Morse as the owner of a saloon at 2059 Evanston Avenue.47

His saloon was just east of St. Boniface Cemetery (sometimes called St. Bonifacius). According to Charles A. Sengstock’s 2004 book That Toddlin’ Town, the roadhouse “mainly served mourners from St. Boniface Cemetery a few blocks to the west.”48

“You go see your dead relatives in the cemetery, and then you go have something to eat and go to the tavern, you know?” Dave Jemilo, the Green Mill’s current owner, told me when I interviewed him for WBEZ in 2020. “That was like a wayside while you’re going to the cemetery. … Yes, I heard that too. That would have been what Pop Morse’s Roadhouse was catering to.”49

But the Tribune obituary for Morse suggests that his roadhouse may have been more closely linked with a different graveyard: Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Evanston. That may seem odd, because the Green Mill is much closer to St. Boniface than it is to Calvary, which is four miles to the north. But the roadhouse was located on Evanston Avenue, which was known as “the road to Calvary.” For people traveling from Chicago up to Calvary and then returning to the city, Pop Morse’s saloon was a convenient stopping point. The Tribune wrote:

Morse … conducted a hotel on the “road to Calvary” and his place was well known to funeral parties. An oft heard saying among mourners was that ‘“Pop Mose’ served the best corned beef and cabbage on the road.” None of the old time politicians passed his place without stopping to have a drink and a bite to eat with the proprietor.50

The ethnic orientation of these cemeteries may explain which crowds hung out at which roadhouse. St. Boniface was dominated by German Catholics,51 who frequented the bar just across from the cemetery entrance on Clark Street, where the fare included beer, Limburger cheese, and sausages.52 (That bar was at the site that later became Rainbo Gardens.) Meanwhile, many of the people buried at Calvary were Irish Catholics.53 By serving corned beef and cabbage, Morse’s roadhouse was more likely to attract Irish mourners from Calvary.

Andy Rohan, a lieutenant of detectives in the Chicago Police Department, recalled stopping at Morse’s place with a friend named Bill, whose wife had died. “On the way back from the cemetery we stopped at Pop Morse’s roadhouse and had a feed of corned beef and cabbage,” Rohan said. “It was the only time in my life that I ever saw Bill renig on the K and K. That convinced me that his grief was sincere.” That curious phrase—”renig on the K and K”—was apparently his way of saying “renege on the corned beef and cabbage.” (Or maybe the Tribune simply misspelled “renege.”)54

Charles Morse had his own reasons to mourn in August 1899, when his wife, Annie, died at the age of 47. (She was buried at Calvary, but six years later, her body would be moved to a new family plot in Mount Carmel Catholic Cemetery in Hillside, where her husband and two children were later buried alongside her.) 55

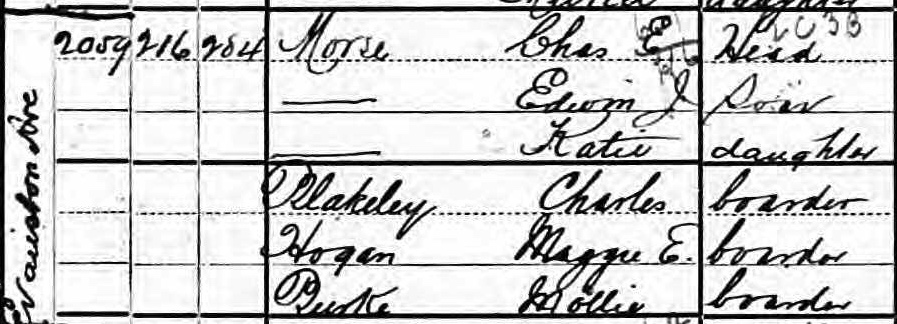

When the U.S. census was conducted in 1900, the 52-year-old widower Charles Morse was living in the same building that housed his saloon. His 30-year-old son, Edwin, was working as a bartender, and his 17-year-old daughter, Katie, was in school. The family also had three boarders, who seemed to be their employees: Charles Blakeley, 49, a waiter, born in New York; Maggie E. Hogan, 42, a cook, born in Wisconsin; and Mollie Burke, 55, a servant, born in Ireland.56

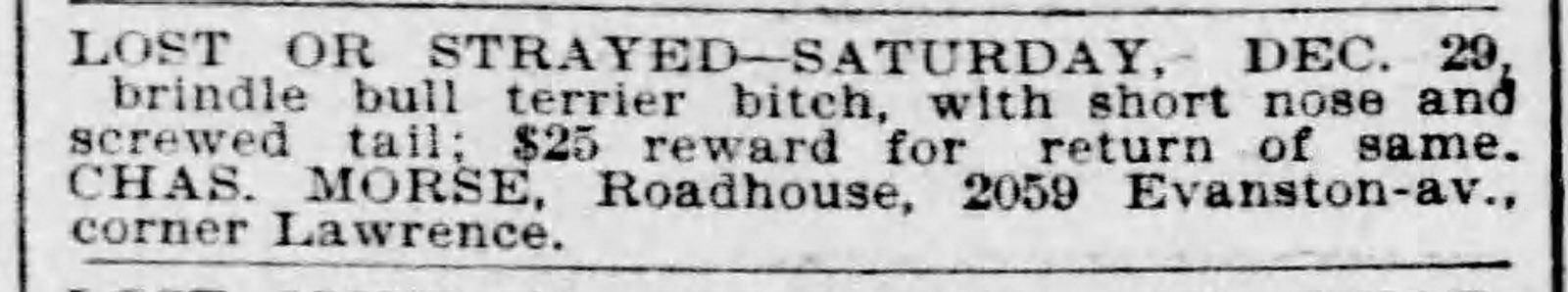

The household also included a dog. When she disappeared at the end of 1900, Morse took out a classified ad in the Tribune offering a reward for it.57

It’s unknown whether Morse found his dog.

A hot spot for boxing

Whenever Pop Morse’s roadhouse was mentioned by newspapers at the turn of the 20th century, it usually had something to do with boxing. It wasn’t just a saloon—it also contained a boxing ring where fighters could spar.58

At the time, prizefighting was a crime under Illinois law: “Whoever, by previous appointment or arrangement, meets another person and engages in a prize fight, shall be imprisoned in the penitentiary not less than one nor more than ten years.” It was also a crime to publicize a fight, train a boxer, or to hold “any sparring or boxing exhibition.”59

Professional boxing would not become legal in Illinois until 1925,60 but officials in Chicago and Cook County frequently allowed boxing matches at the end of the 19th century, and newspapers regularly covered them. City officials veered back and forth between encouraging boxing and prohibiting it. Mayor Carter Harrison allowed boxing matches in some places, but not in others. Sometimes he allowed fights to take place at large venues. At other times, he said boxing should be allowed only in small, private clubs.61

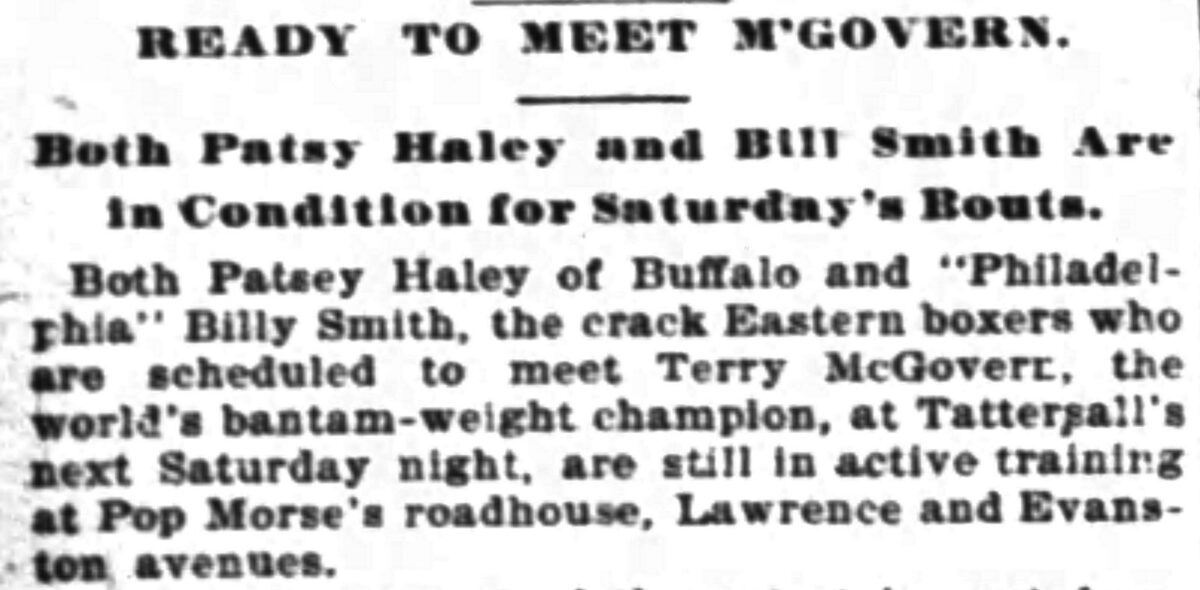

One article described boxer Ed Denfass stepping onto the scales in a backroom at Morse’s roadhouse.62 Two boxers from the East Coast trained at Pop’s place in November 1899, as they prepared for prizefights at Tattersall’s (a large auditorium on Dearborn Street between 16th and 17th Streets). “They do plenty of road work in addition to the ordinary gymnasium exercises,” the Inter Ocean reported.63

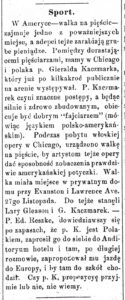

Telegraf, a local Polish-language newspaper, wrote about boxers Gerald Kaczmarek and Larry Gleason fighting on November 27, 1899, at a private house at Evanston and Lawrence Avenues. It’s likely this was Pop Morse’s place.

Telegraf reported that the fight was organized for an opera troupe visiting Chicago, including the Polish singer Edward Reszke —as a way “to give the artists of the opera the opportunity to see a real American skirmish.”64

In 1900, the Inter Ocean described a group of Brooklyn boxers making a “pilgrimage” out to Pop Morse’s roadhouse, where they spent the day training. When their trainer had the pugilists run around the area, they marveled at how bucolic the neighborhood was:

He had them out coursing over the boulevards and pretty parks all morning. The run limbered them up, and the sights they saw delighted the little fellows, who pronounced Chicago ahead of Prospect park for beauty. “It’s all a park,” said Tommy Sullivan. “Great place,” said little Tommy Feltz. …

Johnnie Reagan and Hugh McPadden did not say much, but they did a lot of work during the day. At 5 o’clock the boys donned gymnasium garb and worked for nearly two hours with the bells and clubs, at bag punching, rope skipping, and wrestling. Sullivan and Feltz put on the gloves for several rounds, and then McPadden and Reagan took a turn with the mitts. Then they ate, and then trainer and manager tucked them away in bed.65

That last line suggests that the boxers were lodging at Morse’s roadhouse, which the Tribune had referred to as a “hotel.”66

Chicago city officials effectively prohibited prizefighting in early 1901, a ban that lasted for a quarter century, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago.67 But newspapers continued reported about boxers training at Pop Morse’s roadhouse as late as December 1902.68

During this era, Morse’s roadhouse also served as a starting point for horse races on certain snowy days. Contestants such as Tobe Broderick, a harness racing driver, raced on the streets from Morse’s place to McGarigle’s roadhouse (a.k.a. the Sheridan Drive Club House), at the southwest corner of Wilson Avenue and Clark Street.69

The “L” arrives

The quaint days of horse races in the streets faded away with the arrival of elevated trains and automobiles. The neighborhood around Morse’s roadhouse boomed after the Northwestern Elevated Railroad started running speedy electric trains from the Loop to Wilson Avenue.70 Passengers could walk north from Wilson for just a third of a mile to reach Morse’s saloon.

The first trains arrived at the Wilson station on May 31, 1900. On the following Sunday, some 75,000 people rode the “L” north from downtown, carrying picnic baskets and bottles of beer as they wandered west from the Wilson station into the Sheridan Park residential area.

It was a neighborhood of colonial houses with wide porches, surrounded by gardens and sprawling lawns—a “sylvan” landscape without any fences in sight—and the tourists “swooped down on the North Shore lawns like jaunty grasshoppers,” the Inter Ocean reported. Some of them hopped onto streetcars for Evanston. Homeowners in Evanston (a dry town) and Sheridan Park were alarmed by this invasion of “the common, ordinary feet of plain Chicago people who eat cookies and peanuts and fried chicken and go picnicking on Sunday,” as the Inter Ocean put it. The newspaper’s headline declared: “Beer Gives Them Fits.” 71

To read more on this topic, see Addendum: The “L” Arrives at Wilson.

In November 1905, the Tribune reported that Chicago’s mayor, reform Democrat Edward F. Dunne, gathered with some of his political associates at Pop Morse’s roadhouse for “a quiet, confidential gathering of friends.” (Dunne, a former judge who later became the governor of Illinois, lived at 3127 Beacon Street, which is now 4500 North Beacon Street, just six blocks from the Green Mill.72) But a rival political faction tipped off reporters about the meeting.

“When the mayor and his friends sat down to their quiet conference in one of the quiet dining rooms of the road house the reporters were waiting patiently in the barroom for news from the front.” The Tribune’s report offers a glimpse at the sort of items Chicago politicians would order at a saloon in the early 20th century: “seven bourbons and two ryes … four bourbons and one rye … nine mild Havanas … four crême de menthes … glasses of yellow chartreuse … nine glasses of mineral water …”73

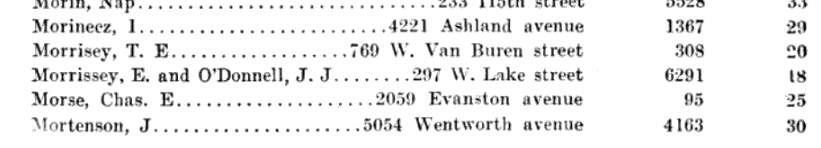

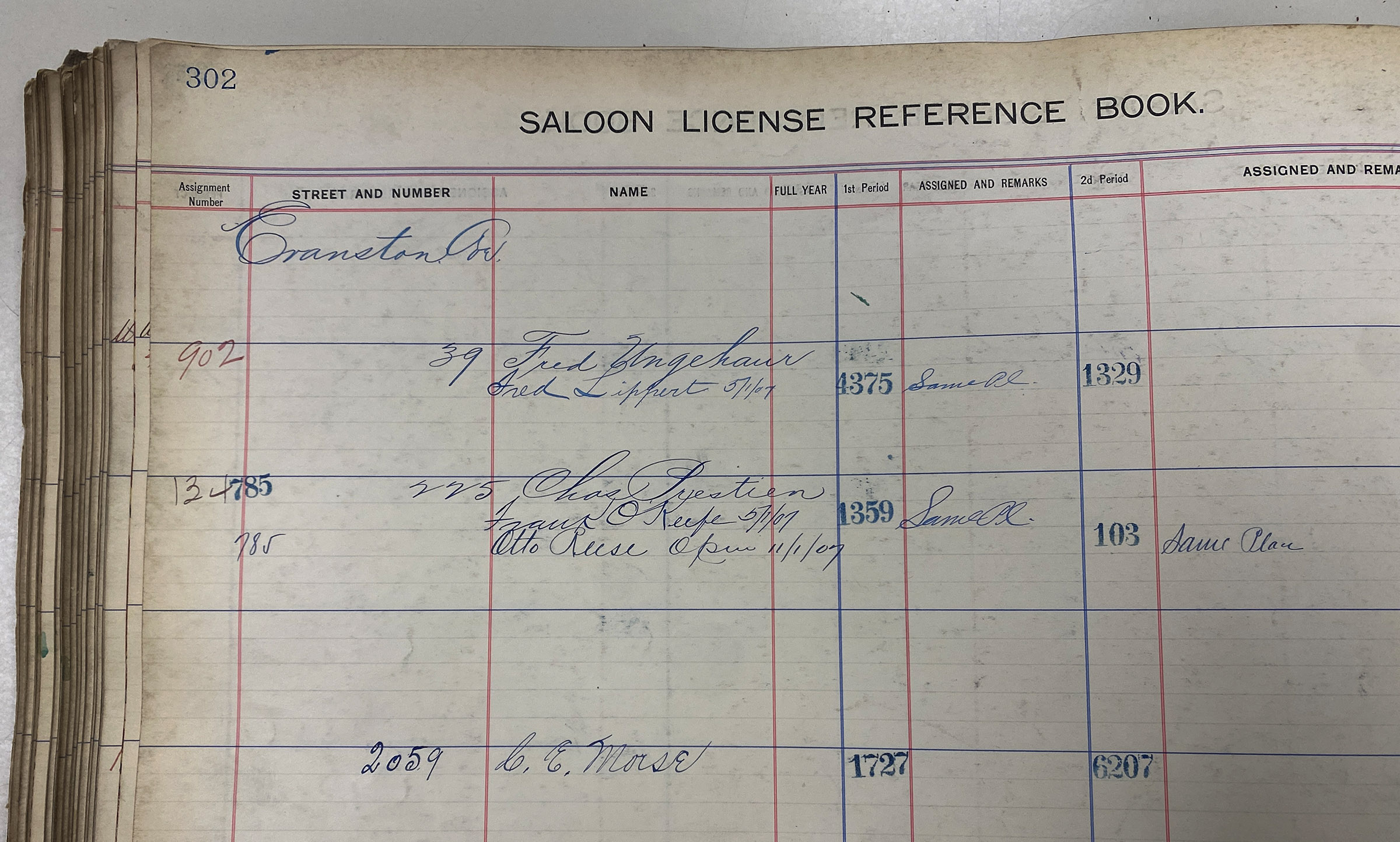

Morse’s saloon at 2059 Evanston Avenue appeared on a complete list of all Chicago saloon licenses, which the city collector presented to the City Council on October 22, 1906. (The list runs for 148 and a half pages—starting here—including roughly 7,500 saloons.)74

Morse’s saloon was also listed in a 1907 ledger of Chicago saloon licenses, which is now part of the Illinois Regional Archives Depository‘s collection at Northeastern Illinois University’s library.75 This archive is a terrific resource for old city and county documents. Alas, even though the list of documents includes saloon license records going back to 1890, I was unable to find any licenses from earlier than 1907.

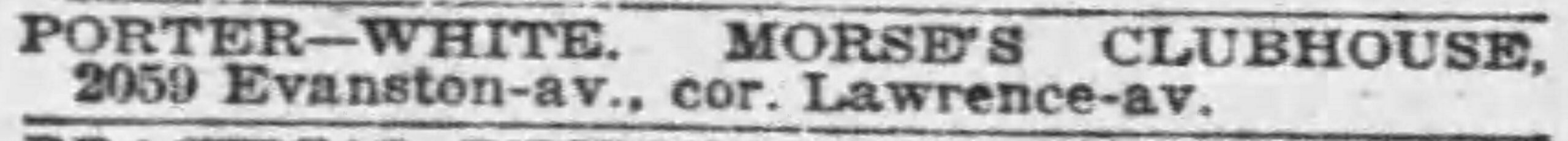

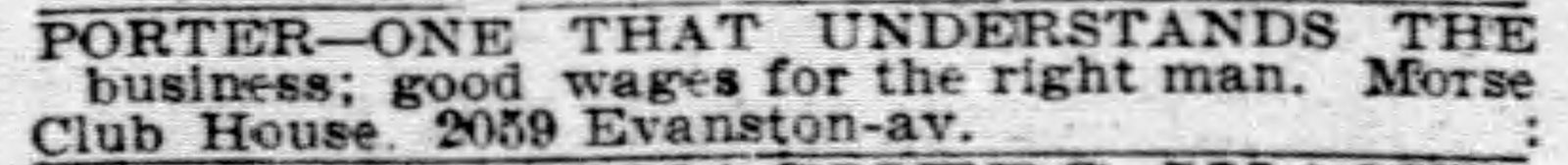

In 1905 and 1907, the Tribune ran classified ads seeking porters to work at Morse’s place. One of these ads specified that job applicants needed to be white. 76 77

Note that both ads referred to the saloon as a “clubhouse.” Was an actual club of some sort affiliated with it? The Tribune also used that term when it mentioned the place in a November 25, 1907, report about the Chicago Law and Order League‘s attempts to shut down saloons on Sundays:

The roadhouses that lined the approaches to Rosehill, St. Boniface, Graceland, and Cavalry cemeteries had their usual popularity with returning funeral processions. Their carriage sheds were filled, while the “mourners” drowned their sorrow inside the saloons. …

The Winona, the Argyle, the Sheridan, and Morse’s clubhouses all reported that some of their “best” customers had remained at home because public attention had been called to the doors of the saloons. 78

The end of the Pop Morse era

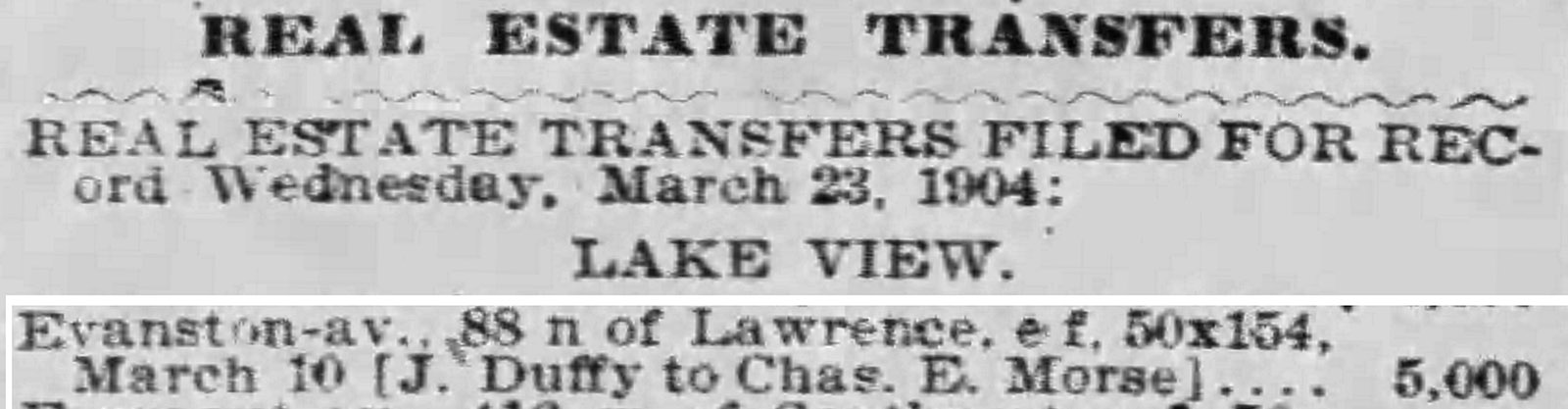

Pop Morse seemed to have had plans for expanding his roadhouse. On March 10, 1904, he paid Joseph Duffy $5,000 to purchase the two vacant lots immediately north of the three lots he already owned.79

A Sanborn fire insurance atlas from 1905 shows the neighborhood’s growth since the previous atlas was published in 1894: More buildings stand on the blocks surrounding Morse’s roadhouse, although there were still many vacant lots.80

It’s unknown whether Morse ever did anything with those extra lots he’d purchased. Charles E. “Pop” Morse died on November 12, 1908,81 shortly after he was stricken with paralysis at his roadhouse. He was 60 years old.82

His son had died the previous year at the age of 27—the ninth of Morse’s children to die.83 And so, Morse’s estate was inherited by the only child who was still alive, his 27-uear-old daughter.84 She’d married Charles Hoffman at the end of 1903, and her name was now Catherine Hoffman.85

The documents from probate court cases are available from the Clerk of the Circuit Court of Cook County’s Archives Department at the Daley Center, where you can page through the old probate index books. The Ancestry.com subscription genealogy website also has searchable indexes to Cook County’s probate cases. The actual documents are stored in a suburban warehouse, however, so you have to request them at the Daley Center and then wait (sometimes for more than a month) for them to be retrieved. They’re a great historical resource, because they often contain details about what someone possessed at the time of their death.

Catherine’s inheritance included the five lots on the west side of Evanston Avenue just north of Lawrence Avenue. When her father died, he owed $6,000 on an $8,000 trust deed he’d taken out on the land. An inventory of Morse’s estate showed that he also owned other two properties, elsewhere in Chicago.

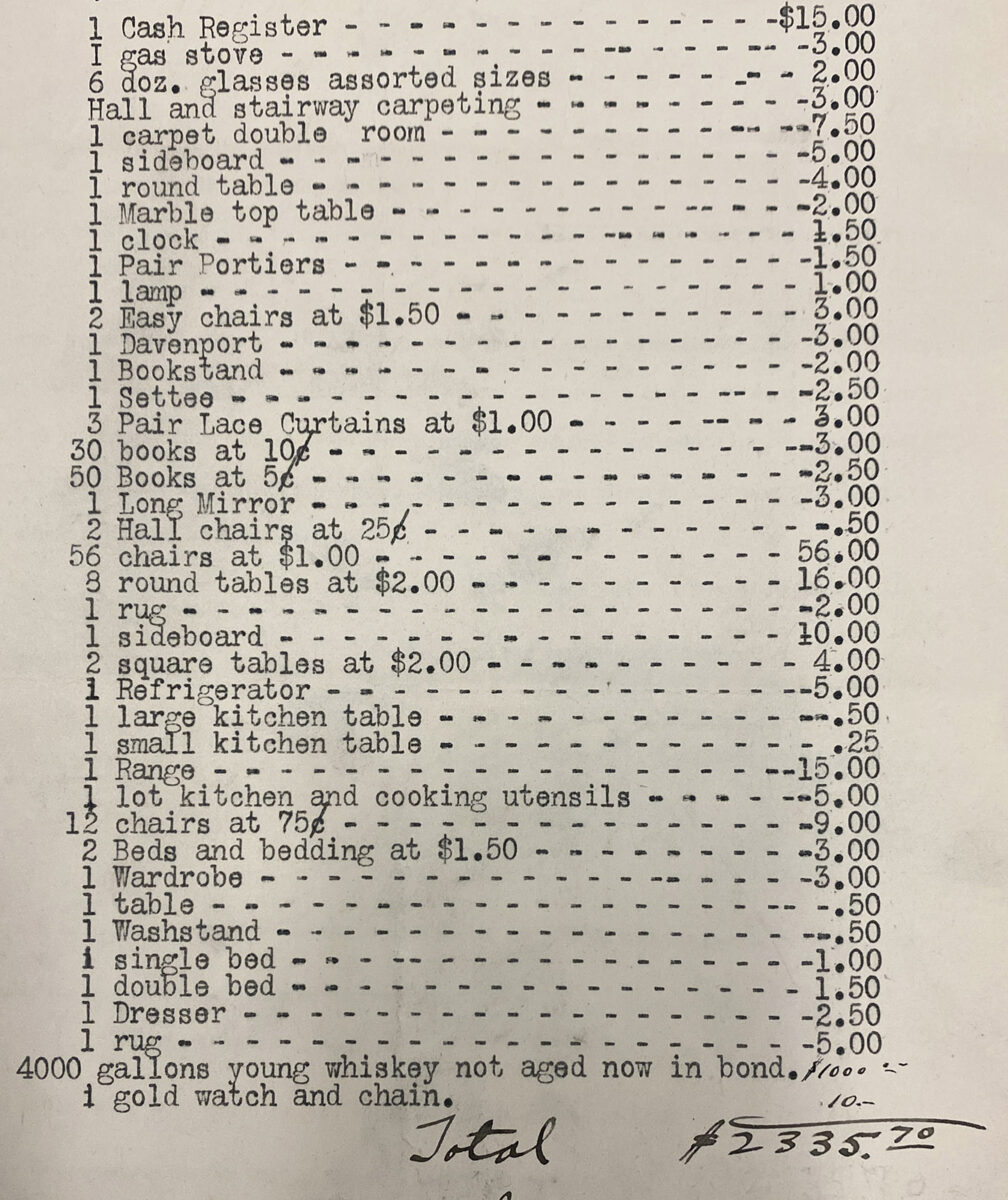

Morse had a $5,000 life insurance policy, $2,250 in a commercial account at Foreman Brothers Bank, and $129 at Edgewater Bank. His assets included a liquor license issued by the city of Chicago—along with the contents of his saloon and home, with a total value of $2,325.70.

The inventory lists a lot of liquor, offering a picture of what it took to run a saloon and roadhouse in this part of Chicago in the early 20th century. At the time of his death, Morse had 4,000 gallons of “young whiskey not aged” and 360 gallons of Anderson Club Whiskey, plus another 28 gallons of various kind of liquor, 25 gallons of beer, five gallons of ale, and more than 46 gallons of wine.

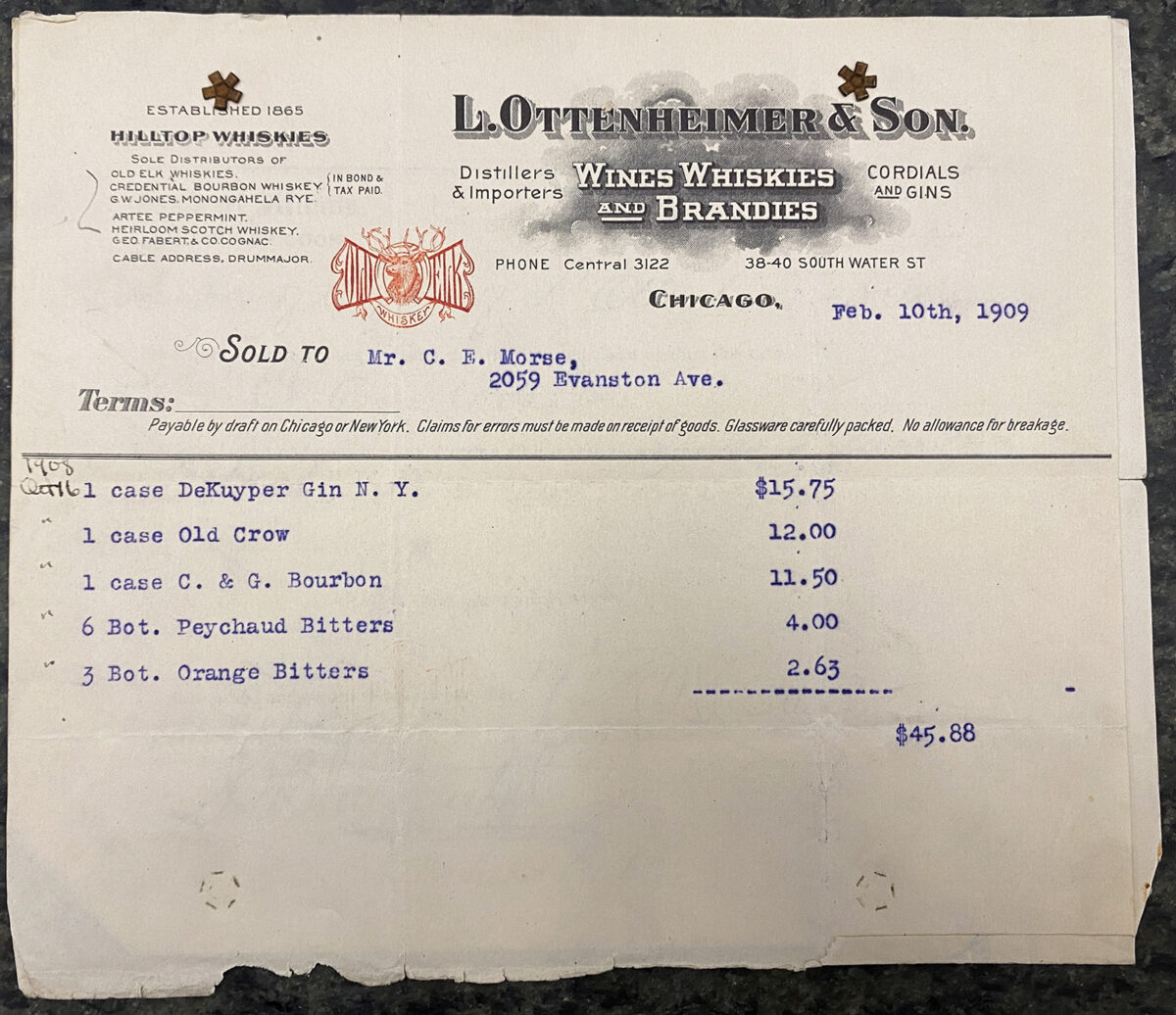

Morse’s unpaid bills included a $45.88 tab from L. Ottenheimer & Son Distillers and Importers.86

He also had 1,500 cigars at his saloon—and when he died, he owed $40 to the Barrett Cigar Co. for a recent purchase of 500 cigars. The most valuable furnishings in his saloon were the back bar, worth $300, and the front bar, worth $100. Morse’s personal belongings included 80 books.87

Charles Hoffman and his brother Frank took over the roadhouse, and for at least a short time, it was known as the Hoffman Bros. saloon.88 According to a report by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, Charles Hoffman opened a small beer garden on the property in 1909, adding a frame pavilion for outdoor entertainment.

The same year, the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company opened studios at 1333–45 West Argyle Street, five blocks northwest of the roadhouse,89 which reportedly became a hangout for Essanay’s actors and film crew members. And 1909 was also the year when Chicago changed its street numbers; without moving an inch, the roadhouse got a new address: 4800 Evanston Avenue.

The Hoffmans didn’t run the saloon for long. In 1910, they made a deal with a well-known Chicago saloonkeeper and restaurateur, Greek immigrant Tom Chamales, for him to manage the roadhouse. Four years later, Chamales would transform the site into the palatial Green Mill Gardens.

The myth of 1907

So … where does the notion that the Green Mill began in 1907 come from?

It’s hard to say precisely where that misinformation originated. But it looks like Steve Brend played a role in spreading it. Brend—who started working at the Green Mill in the late 1930s and owned the bar from 1960 until 1986—was the source of many stories about the nightclub’s history.

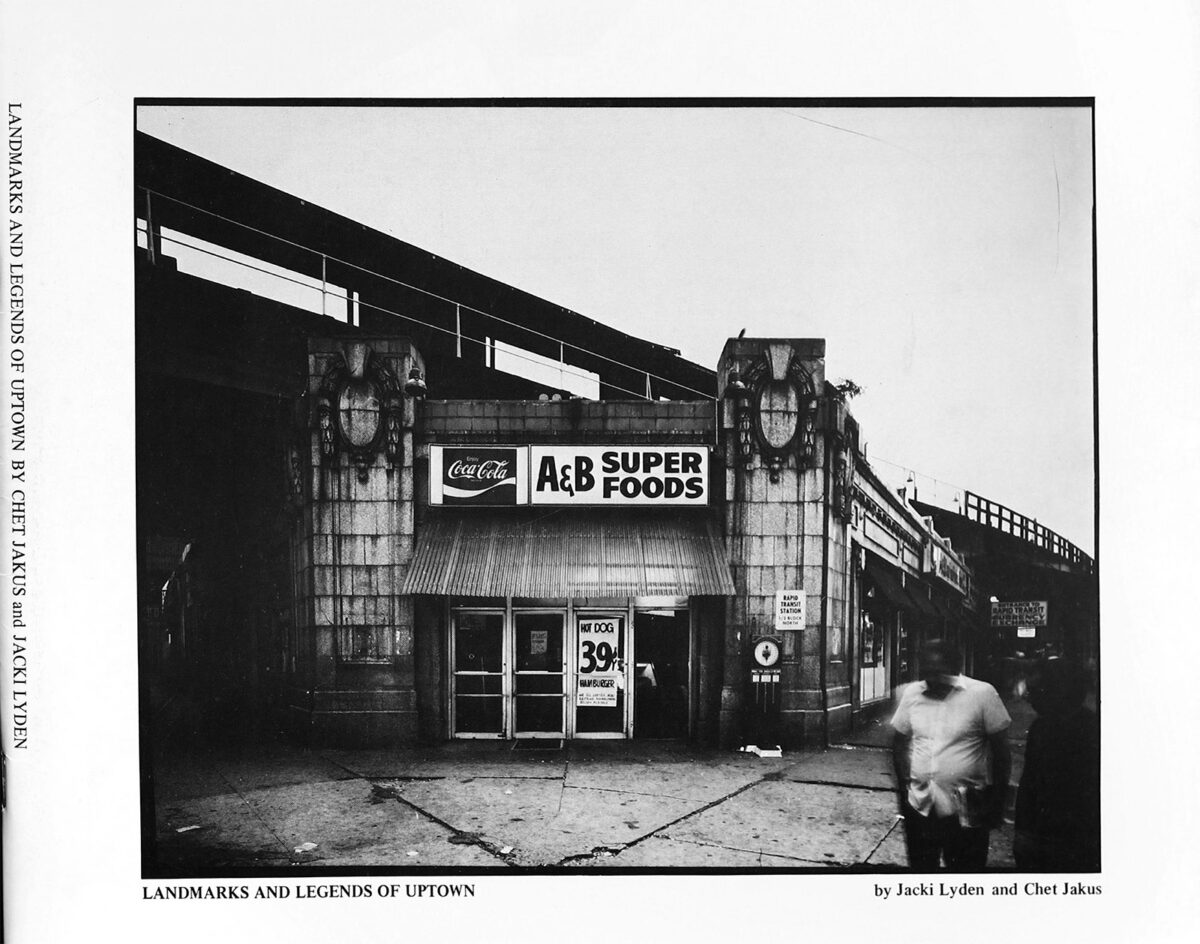

When journalist Jacki Lyden interviewed Brend for her self-published 1980 book Landmarks and Legends of Uptown, he told her: “ … about how this place began, well it was Pop Morse’s Roadhouse in 1907. This was just a crossroads then and all the people in funeral processions on their way to St. Boniface’s cemetery on Lawrence used to stop here. They’d come by and get something to eat.”90

(Yes, that’s the same Jacki Lyden who later became a reporter and host on National Public Radio. I emailed her and asked if she had audio of her interview with Brend. She replied: “Alas, I have no audio of Brend, though I can hear him plain as day.”91)

Another journalist, Robert Ebisch, interviewed Brend for the Chicago Reader in 1982. His article also says Pop Morse’s roadhouse opened in 1907. This information isn’t specifically attributed to Brend, but it’s possible Ebisch heard it from him.92

Brend was also interviewed by Chicago Sun-Times reporter Rick MacArthur in 1980. “The original Green Mill Gardens opened in 1906,” MacArthur wrote, setting the origin one year earlier. That wasn’t attributed, either.93

All of these articles make it clear that Brend (who died in 2006 94) was a colorful storyteller. It’s entertaining to read about him telling the various tales he’d heard about the Green Mill’s early history. As the Chicago Reader put in 1982, “anecdotes begin rolling out like an avalanche.”

But like just about anyone retelling stories they’d heard decades earlier, Brend got some facts wrong. It’s possible someone once told Brend that Pop Morse opened his roadhouse in 1907. Or maybe Brend misremembered what year it opened. In any case, 1907 isn’t correct.

But once this “fact” made it into print, it was repeated by other writers. For a while, the Green Mill’s website included a page about the club’s history, which repeated the same incorrect information about 1907. (The website no longer has that page, but you can see a saved copy of it from 2007 at archive.org.)95

The misinformation has been written so many times now that it may be impossible to kill. And if you use 1907 as the starting point for the Green Mill’s story, you’ll miss a lot of history from before that.

Continue to Chapter 2: Piecing Together the Green Mill Puzzle

<— INTRODUCTION / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

FOOTNOTES

1 “Evanston Avenue Becomes Broadway With Midnight,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 15, 1913.

2 “Old ‘Pop Mose’ Is No More,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 13, 1908, 22.

3 1900 U.S. Census, Chicago Ward 25, Enumeration District 772, sheet 13B.

4 Massachusetts, State Census, 1855, Northampton, Hampshire, Household 751, Reel 13, Volume 18, at Ancestry.com.

5 “Old ‘Pop Mose’ Is No More.”

6 1874 city directory, at Fold3.com.

7 Alson J. Smith, Chicago’s Left Bank (Chicago: H. Regnery, 1953), 137, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t2n59kz0z?urlappend=%3Bseq=148.

8 Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan, Lords of the Levee: The Story of Bathhouse John and Hinky Din. (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1943. Reprinted, Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2005), 336-337; “1903—Workingmen’s Exchange,” Chicagology, accessed March 17, 2023, https://chicagology.com/notorious-chicago/kennasaloon/. ; “The Workingmen’s Exchange,” The Chicago Crime Scenes Project, January 26, 2009, http://chicagocrimescenes.blogspot.com/2009/01/workingmans-exchange.html.

9 “Chinatown,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/284.html.

10 “Old Chinatown,” Preservation Chicago, March 4, 2016, https://preservationchicago.org/chicago07/old-chinatown/.

11 “Deaths,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 16, 1907; California, U.S., Death Index, 1940-1997, Ancestry.com.

12 1900 U.S. Census, Chicago Ward 25, Enumeration District 772, sheet 13; Tract Book 543 A-2, 217, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division; Find a Grave, accessed February 24, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/244088113/edward-j-morse.

13 Testimony of Catherine Hoffman, proof of heirship, December 28, 1908, estate of Charles E. Morse, 4-8818, Probate Court of Cook County.

14 1880 U.S. Census, Colorado, Summit, Carbonateville, Enumeration District 105, A.

15 Mary Ellen Gilliland, “Summit Historic Yesterday’s: The Crook of Carbonateville,” April 4, 2016, https://www.summitdaily.com/explore-summit/history/summit-historic-yesterdays-the-crook-of-carbonateville/ Excerpt from Mary Ellen Gilliland, Colorado Rascals, Scoundrels, and No Goods of Breckenridge, Frisco, Dillon, Keystone and Silverthorne (Vail, CO: Alpenrose Press, 2005).

16 1880 U.S. Census, Colorado, Summit, Carbonateville, Enumeration District 105, A.

17 “Old ‘Pop Mose’ Is No More.”

18 Don L. Griswold and Jean Harvey Griswold, The Carbonate Camp Called Leadville (Denver, CO: University of Denver Press, 1951), 175.

19 Griswold and Griswold, Carbonate Camp, 170-177.

20 “Notes,” (Pueblo) Colorado Weekly Chieftain, May 13, 1880, 2, https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=CCF18800513-01.2.7&srpos=20.

21 “Arrested for Murder,” Leadville (CO) Weekly Herald, August 27, 1881, 6, https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=LWH18810827-01.2.55&srpos=4.

22 “Old ‘Pop Mose’ Is No More.”

23 Ricky Jay, Celebrations of Curious Characters (San Francisco: McSweeney’s Books, 2011), 19.

24 Clifton R. Wooldridge, Twenty Years a Detective in the Wickedest City in the World (Chicago: Chicago Publishing, 1908), 27. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47445/47445-h/47445-h.htm.

25 1883 city directory, Fold3.com.

26 California, U.S., Death Index, 1940-1997, Ancestry.com.

27 1885–1889 city directories, Fold3.com.

28 “Custom House Place,” Chicago Crime Scenes Project, September 2, 2008, http://chicagocrimescenes.blogspot.com/2008/09/custom-house-place.html.

29 “A Notorious Character Shot,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 10, 1888, 3.

30 “In General,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 26, 1886, 8; “Miscellaneous,” Inter Ocean, January 26, 1889, 8.

31 “Local Real Estate Transactions,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 10, 1889, 9; Tract Book 543 A-2, 217, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

32 City of Chicago 80-Acre Sheets, accessed February 25, 2023, https://gisapps.chicago.gov/gisimages/80acres/pdfs/esw084014r.pdf.

33 Charles Rascher, Rascher’s Atlas of Lake View Twp., Cook Co. Ill. (Chicago: Charles Rascher, 1887), Sheet 37, accessed March 2, 2023, http://www.historicmapworks.com.

34 Karen Donnelly and LeRoy Blommaert, “!!EXTRA !! EXTRA!! Annexation Approved,” Edgewater Scrapbook 1, no. 4 (Summer 1989), http://www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/articles/v01-4-4.

35 “Beer Gives Them Fits,” Inter Ocean, June 17, 1900.

36 “Site on the North Side,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 8, 1890, p. 1.

37 Chicago, Vol. A (Sanborn-Perris Map Company, 1894), https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4104cm.g017901894A/?sp=1.

38 Commission on Chicago Landmarks, Dover Street District Landmark Designation Report, January 4, 2007, 5, https://www.chicago.gov/dam/city/depts/zlup/Historic_Preservation/Publications/Dover_Street_District.pdf.

39 Chicago city directories, 1891–1896, Fold3.com.

40 LeRoy Blommaert, “Edgewater’s Second Railroad,” Edgewater Historical Society, accessed February 25, 2023, http://www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/local/edgewaters-second-railroad.

41 LeRoy Blommaert, “Streetcar Lines: The Broadway Line: Edgewater’s First Trolley,” Edgewater Historical Society, accessed February 25, 2023, http://www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/local/streetcar-lines-broadway-line.

42 Tract book 543 A-2, 217, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

43 Permit 338, May 13, 1897, Chicago Building Permit Ledgers Reel UID CBPC_LB_06 86, Chicago Building Permits Digital Collection 1872-1954, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, https://researchguides.uic.edu/CBP.

44 Real Estate and Building Journal, May 29, 1897, 431. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t0ps1fv78?urlappend=%3Bseq=435.

45 Tract book 543 A-2, 217, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

46 Chicago, Vol. 17 (New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1905), 79. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4104cm.g01790190517/?sp=80&r=-0.093,0.841,1.057,0.733,0.

47 1898 Chicago city directory, Fold3.com.

48 Charles A. Sengstock, That Toddlin’ Town: Chicago’s White Dance Bands and Orchestras, 1900–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2004), 61.

49 Telephone interview with Dave Jemilo, March 11, 2020.

50 “Old ‘Pop Mose’ Is No More.”

51 “St. Boniface Cemetery Burials,” Genealogy Trails, accessed February 26, 2023, http://genealogytrails.com/ill/cook/cem/stboniface_cem.html.

52 “A Happy Combination,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 27, 1888.

53 “Calvary Catholic Cemetery,” Find a Grave, accessed February 26, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/105009/calvary-catholic-cemetery.

54 “Proving Grief, Two Find Joy,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 25, 1909, 3.

55 Illinois Statewide Death Index, Pre-1916 Illinois State Archives, https://www.ilsos.gov/isavital/deathSearch.do; “Official Death Record,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 17, 1899, 5; Find a Grave, accessed February 24, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/244083018/annie-m-morse; Illinois, Cook County Deaths, 1871-1998, database, FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:N78S-YNT.

56 1900 U.S. Census, Chicago Ward 25, Enumeration District 772, sheet 13B.

57 Classified advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, January 6, 1901.

58 “Carter-Gardner Forfeit Is Up,” Inter Ocean, December 23, 1902.

59 Harvey B. Hurd, ed. and comp., The Revised Statutes of the State of Illinois, 1901 (Chicago: Chicago Legal News Company, 1901), chapter 38 § 231–236, 633-634, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112105473971?urlappend=%3Bseq=665%3Bownerid=13510798902240829-689.

60 “73. An Act to Regulate Athletics and Legalize Boxing in Illinois (1925),” Office of the Illinois Secretary of State, accessed March 19, 2023, https://www.ilsos.gov/departments/archives/online_exhibits/100_documents/1925-regulate-athletics-legal-boxing.html.

61 “Boxing May Be Discontinued,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 10, 1899; George Siler, “Mayor Forbids Boxing Planned,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 25, 1901; George Siler, “Makes No Move Against Fights,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 8, 1903; George Siler, “Chicago Boxing Clubs Are Safe,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 11, 1903.

62 “Denfass Hard at Work,” Inter Ocean, February 16, 1900.

63 “Ready to Meet M’Govern,” Inter Ocean, November 14, 1899.

64 “Sport,” Telegraf, December 20, 1899.

65 “Eastern Men at Work,” Inter Ocean, September 10, 1900.

66 “Old ‘Pop Mose’ Is No More.”

67 Robert Pruter, “Boxing,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/159.html.

68 “Carter-Gardner Forfeit Is Up,” Inter Ocean, December 23, 1902.

69 Letter signed “J.D.,” to “In the Wake of the News” column, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 21, 1924, 11.

70 Landmark Designation Report: Uptown Square District, 5.

71 “Beer Gives Them Fits,” Inter Ocean, June 17, 1900.

72 1905 Chicago city directory, Fold3.com.

73 “Mayor Led Among False Friends,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 24, 1905, 2.

74 Chicago City Council Proceedings, Oct. 22, 1906, 1645, https://books.google.com/books?id=bLkVAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1645.

75 Chicago Saloon License Record, 1890–1919, 7/0035/01, Illinois Regional Archives Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

76 Classified advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, March 26, 1905.

77 Classified advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, March 17, 1907.

78 “Imbibe Evidence Across 27 Bars,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 25, 1907, pp. 1, 2.

79 “Real Estate Transfers,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1904; Tract Book 543 A-2, 225, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

80 Chicago, Vol. 17 (New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1905), 79. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4104cm.g01790190517/?sp=80&r=-0.093,0.841,1.057,0.733,0.

81 Cook County, Illinois, Deaths Index, 1878-1922, at Ancestry.com.

82 “Old ‘Pop Mose’ Is No More.”

83 “Deaths,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 16, 1907.

84 Table of heirship, December 10, 1908, estate of Charles E. Morse, 4-8818, Probate Court of Cook County; Illinois, Cook County Probate Court, Record Grants of Administration, Book 22, 1908-1909, 260, at Ancestry.com; Illinois, Cook County Probate Court, Administrators Bonds and Letters, Book 64, 1909, 189, at Ancestry.com.

85 Illinois, Cook County Marriages, 1871-1968, database, FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:N746-8Z.

86 Claim of L. Ottenheimer & Son, September 28, 1909, estate of Charles E. Morse, 4-8818, Probate Court of Cook County.

87 Inventory, December 16, 1908, estate of Charles E. Morse, 4-8818, Probate Court of Cook County.

88 1909 Chicago city directory, Fold3.com.

89 Landmark Designation Report: Uptown Square District, 13.

90 Jacki Lyden, Landmarks and Legends of Uptown (Chicago: Jacki Lyden, 1980), 29.

91 Jacki Lyden email to author, March 5, 2020.

92 Robert Ebisch, “Whatever Happened to the Green Mill,” Chicago Reader, October 29, 1982, 1-2, 20, 22, 24.

93 Rick MacArthur, “Movie Mob Retakes Uptown Bar,” Chicago Sun-Times, April 24, 1980, 97.

94 Death notice, Chicago Tribune, March 17, 2006, section 2, 14.

95 Green Mill website, archived on January 4, 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20070104002103/http://www.greenmilljazz.com/history.html.