This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Pioneer Press on July 10, 2002.

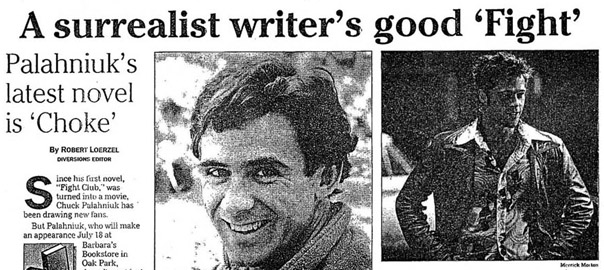

Since his novel, “Fight Club:’ was turned into a movie, Chuck Palahniuk has been drawing new fans.

But Palahniuk doesn’t want just anyone reading his books. His most recently published novel, “Choke,” throws down the gauntlet with its opening lines, daring readers to … well, daring them to stop reading:

If you’re going to read this, don’t bother. After a couple pages, you won’t want to be here. So forget it. Go away. Get out while you’re still in one piece.

Save yourself. There has to be something better on television…

It’s hard to tell whether Palahniuk is being sarcastic when you read him on the page. In a telephone interview, the Oregon writer said he was being somewhat serious when he wrote the opening paragraphs of “Choke,” which just came out in paperback. In a way, that opening is intended as an actual warning. Palahniuk knows that not everyone is going to like his dark and twisted comedic fantasies about social miscreants.

“I wanted to address people who wouldn’t like my stuff,” Palahniuk said. “I wanted to weed them out.”

At the same time, Palahniuk said he realized his warning would, entice some people to read on. Like “Fight Club,” Palahniuk’s latest novel is at times a brutal read. “Choke” isn’t always easy to swallow. This time around, the disturbing elements revolve more around sex than violence. It’s often wickedly funny, though readers looking for wholesome writing will probably find it literally wicked.

The book’s protagonist, Victor Mancini, pretends to choke on food at restaurants so that other diners will leap into action and save him. Part of his motivation is to persuade these “heroes” to support him with periodic checks in the mail; but he also seems enjoy seeing these people feel as if they’ve saved someone’s life.

Victor’s other deviant behavior includes lying to residents at the nursing home where his ailing mother lives. Whenever residents approach him with addled memories about decades-old grievances, he confesses that he’s the person who wronged them years ago, hoping this will give them “closure.” These sorts of schemes — in which a character takes a social situation and turns it upside-down — are typical of Palahniuk’s writing.

He said he was inspired by the con games in movies such as “The Sting,” but Palahniuk wondered if the money was really the main objective of the characters in those stories. “What’s the next step?” he said. “What do they do with that money?”

The characters in Palahniuk’s stories play con games, but instead of seeking money, they’re trying to achieve their emotional needs, he says.

In “Fight Club,” the narrator fills the emotional void in his life by creating clubs where men get together for fistfights. At least, that’s what the story seems to be about, until a stunning revelation comes near the end, totally changing our perspective of everything that has happened until then. (For those who haven’t read the book or seen the movie yet, we won’t spoil the surprise.) The film’s director, David Fincher, followed the same tactic that Palahniuk had used in the original novel to prepare for the shocking plot twist. Both of them preceded it with so many absurd, surreal scenes that the story’s secret wasn’t too hard to accept.

The key, Palahniuk said, is to “get people to swallow a lot of outrageous things.” While many authors are unhappy with the film adaptations of their books, Palahniuk said he couldn’t have been more pleased with the way Fincher vividly brought “Fight Club” to the screen.

“The movie was so good,” he said. “My first panic was people would think I wrote the book after the movie, that it was just some cheesy novelization.”

The success of “Fight Club” prompted some people to contact Palahniuk for information on how to sign up for the nearest fight club in their city. He has had trouble convincing them that the fight clubs were just a figment of his imagination. Palahniuk’s writing seems to inspire a strange devotion among some readers.

“I have received five or six letters from people who want to be my slave,” he said. “If they do windows, I’m totally open to that idea.”

Palahniuk’s fifth novel, “Lullaby,” comes out in September. In this supernatural thriller, a newspaper reporter discovers an old African chant in a book of poems may be causing children to die of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome whenever it is read.

“It’s a really big departure,” Palahniuk said of the book. “I’ve thrown my formulas out the window. I’ve decided to spend my next three books reimagining the horror novel.”

What fascinates Palahniuk about old horror novels, he said, is the subtext. What were people really afraid of in their lives when they shivered about tales of vampires and werewolves? “The monsters personified the fears of the time,” Palahniuk said.

Like most authors, Palahniuk said his fiction is not autobiographical, although it does reflect certain aspects of his personality and experience. “None of it is me, but all of it is me, in some way,” he said. “Usually, I’m making fun of myself, some aspect of my life that’s ludicrous and stupid.”